WCPFC Objective

The Objective of the WCPFC is found in Article 2 of the Convention, as follows:

The objective of this Convention is to ensure, through effective management, the long-term conservation and sustainable use of highly migratory fish stocks in the western and central Pacific Ocean in accordance with the 1982 Convention[1] and the Agreement.[2]

To support this Objective, the Convention sets out key principles and measures for conservation and management (Article 5), summarized below.

- Sustainability and Optimal Utilization: Members must adopt measures to ensure the long-term sustainability of highly migratory fish stocks and promote their optimum use within the Convention Area.

- Science-Based Management: All measures must rely on the best available scientific evidence, aiming to maintain or restore fish stocks to levels that can produce maximum sustainable yield, accounting for environmental, economic, and social factors, especially the needs of developing States, including small island developing States.

- Precautionary Approach: Members must act cautiously when information is uncertain, and must not delay conservation action due to lack of scientific certainty.

- Ecosystem Considerations: Impacts of fishing and other human or environmental factors must be assessed across target and non-target species, and the broader marine ecosystem.

- Minimizing Harm: Measures must be taken to minimize waste, discards, gear loss, and pollution, and to reduce bycatch of non-target and endangered species by promoting selective, safe, and efficient fishing gear.

- Biodiversity and Habitat Protection: The marine environment and habitats of special concern must be protected to maintain biodiversity.

- Managing Fishing Effort and Capacity: Overfishing and excess capacity must be prevented, ensuring fishing effort aligns with the sustainable use of resources.

- Inclusivity and Fairness: The interests of artisanal and subsistence fishers must be considered in conservation and management decisions.

- Data Sharing and Transparency: Members are expected to collect and share accurate, timely data on vessel positions, catches (target and non-target), fishing effort, and relevant research.

- Effective Compliance: Conservation measures must be enforced through robust monitoring, control, and surveillance systems.

WCPFC's Conservation and Management Framework

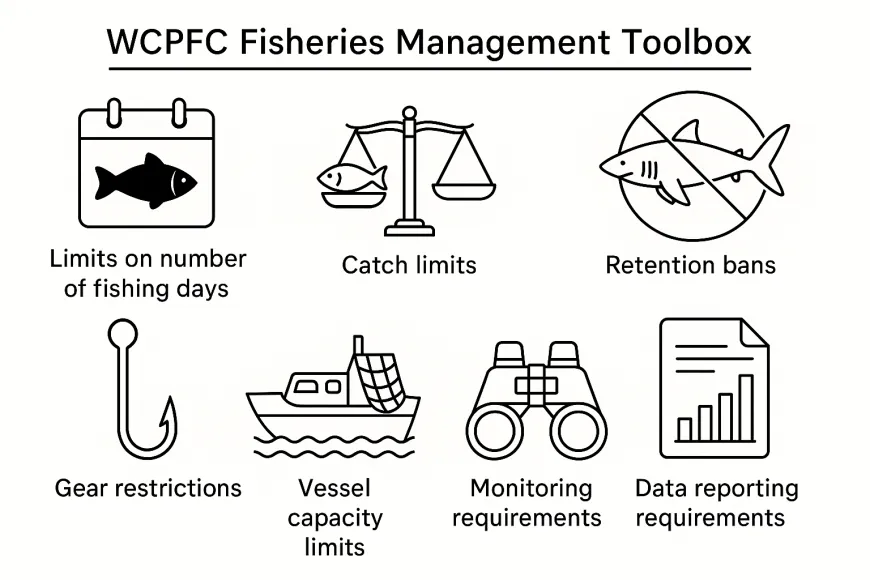

The WCPFC uses a variety of tools to sustainably manage tuna and billfish in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean and to accomplish its objective. These include setting limits on how many fish can be caught, how many days fishing vessels can operate, and when certain gear, such as fish aggregating devices (FADs), can be used. The Commission also runs monitoring programmes to keep track of fishing activity, including collecting data and information on fishing activities. All of these tools work together to make sure these important fish populations stay healthy and can be enjoyed by future generations.

In 2014, the Commission adopted a plan to develop and implement a Harvest Strategy Framework to manage fish stocks. Harvest strategies replace reactive, ad hoc decision-making with predefined, rule-based management actions, triggering adjustments to catch limits or effort controls automatically as stock assessments indicate changes, thereby reducing time lags, minimizing overfishing risk, and enhancing transparency and stakeholder confidence. See the Harvest Strategy Framework page for more details on WCPFC's efforts to enhance adaptive management of key tuna stocks in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean.

Until harvest strategies are in place for key stocks, the Commission continues to adopt a range of conservation and management measures to ensure stock sustainability.

Scientific advice for the WCPFC-managed tuna and billfish stocks is provided by the WCPFC's Scientific Services Provider (SSP): the Oceanic Fisheries Programme at the Pacific Community (OFP-SPC). Scientific advice for Pacific bluefin tuna, North Pacific albacore, North Pacific swordfish, and North Pacific striped marlin is provided by the International Scientific Committee for Tuna and Tuna-Like Species in the North Pacific Ocean (ISC).

Click on any of the links below to learn more about how the WCPFC works to conserve and manage key tuna and billfish stocks.

🐟 WCPFC Stock Status Terminology

This guide explains the core indicators used by the WCPFC to track tuna stock health and sustainability. These are the terms you’ll see in stock assessments, harvest strategies, and WCPFC plots like the Majuro Plot.

📘 Definitions and Descriptions

Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY): the biggest average catch you can take long‑term without running the stock down.

Spawning Stock Biomass (SSB): the total weight of mature fish in a stock, i.e. those capable of reproducing. It represents the reproductive engine of the fish population.

SSB_recent: the current (or recent‑year average) amount of mature fish able to reproduce.

SSB_F=0: what that reproductive biomass would be in the same recent period if there were no fishing (a useful “unfished” baseline.)

Target Reference Point (TRP): the aim point—a level we try to reach or stay at to keep the fishery sustainable and stable.

Limit Reference Point (LRP): the do‑not‑cross line—if the stock falls below it, managers act quickly to rebuild.

Depletion ratio = SSB_recent/ SSB_F=0: shows the share of unfished spawning potential that remains.

Harvest Control Rule (HCR): A harvest control rule is like a set of traffic lights for fishing. It’s a pre-agreed plan that tells managers what actions to take depending on the health of a fish stock.

Effort Creep: Refers to the gradual increase in the effective fishing power of vessels or fleets, even when nominal fishing effort (such as the number of vessels, days at sea, or gear units) appears to remain constant. For example, suppose a fleet is limited to 100 fishing days per year. If new technology allows vessels to catch 20% more fish per day, then even without increasing the number of days, the fleet’s effective effort has increased, potentially leading to overfishing unless management adjusts.

📌The term "CCM" refers to Members, Cooperating Non-Members, and Participating Territories. Visit the "Who We Are" page to learn more about WCPFC's membership.

North Pacific Albacore Tuna

| Stock Status | Stock is not overfished and overfishing is not occurring |

| Main Fishery Participants | Canada, China, Cook Islands, Japan, Chinese Taipei, Vanuatu |

Image

| 2024 Catch Volume in the WCPFC Convention Area | 51,052 metric tonnes |

All data is current as of 1 January 2026. | ||

🐟 Understanding the Stock

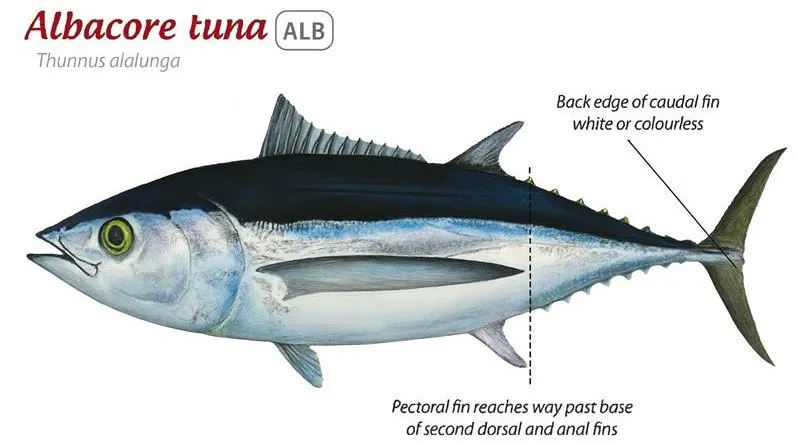

Albacore tuna (Thunnus alalunga) is one species, but fisheries scientists treat the North Pacific and South Pacific populations as two distinct management stocks. Why? Because oceanographic barriers, unique migration routes, and limited mixing make them functionally separate.

Each stock’s specific biology, such as growth, spawning, and movement, is factored into assessments, allowing targeted, science-based management to ensure long-term sustainability.

In the WCPFC, management of the North Pacific albacore fishery is led by the Northern Committee. Scientific advice for this stock is provided by the International Scientific Committee on Tuna and Tuna-Like Species in the North Pacific Ocean.

🌊 Stock & Fishery Health

Stock Condition

The stock is in good biological condition. Scientific assessments show that North Pacific albacore is not overfished, and overfishing is not occurring.

The spawning biomass is estimated at over three times the minimum safe limit. Fishing pressure is low and sustainable.

Fishery Status

The fishery involves troll and longline fleets, with trolling focused on juveniles and longline targeting adults.

The U.S. and Japan are key players, though catch volumes (e.g., ~1,626 mt from U.S. troll fishery in 2022) have declined from historical highs. Canada is also a main participant in this fishery.

Catch levels fluctuate due to environmental factors and market dynamics, not necessarily because of poor stock health.

💰 Economic & Social Importance

Coastal Livelihoods

The fishery supports small-scale and artisanal fleets, especially in coastal communities in the U.S. and Japan.

It provides jobs, income, and local food sources, and is a potential entry point for small island developing States (SIDS) interested in developing their domestic fisheries.

Trade & Regional Value

Albacore is a source of high-quality tuna, valued for canned products and export markets.

It is a strategic species for developing regional economies and strengthening control over ocean resources.

📊 Scientific Assessment

Latest Findings

The International Scientific Committee for Tuna and Tuna-Like Species in the North Pacific Ocean (ISC) conducts the stock assessment on North Pacific albacore for the WCPFC. The 2023 ISC assessment (latest available) confirms a healthy and stable stock.

Spawning biomass (SSB2022) is 3.44% of the limit reference point, and fishing mortality is well below levels that would reduce sustainability.

Scientific Advice

Maintain current fishing levels.

Improve data on juvenile catch and gear selectivity.

Monitor recruitment variability and account for climate change effects on albacore movement and productivity.

⚖️ Management Framework

WCPFC Conservation Measure (CMM 2019-03)

Limits fishing effort to 2002–2004 average levels.

Requires annual reporting by gear type and supports science-based monitoring.

Encourages collaboration with the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC) for consistent regional governance.

Special Consideration for SIDS

Allows Small Island Developing States to grow their own fisheries without triggering foreign overexploitation.

Balances development rights with conservation commitments.

⚠️Management Challenges & Future Improvements

Ongoing Issues

- Enforcing effort limits is challenging.

- Data gaps remain, especially for longline catch per unit of effort (CPUE) and juvenile stock components.

- Climate-driven changes may alter albacore distribution and productivity.

Path Forward

- Develop Harvest Strategies, including target reference points and harvest control rules.

- Advance Management Strategy Evaluation (MSE).

- Strengthen regional coordination between WCPFC and IATTC.

- Incorporate environmental indicators to support adaptive, climate-ready management.

🧭 Summary

The North Pacific albacore fishery is a well-managed, sustainable tuna resource that supports economic and subsistence fisheries across multiple nations. Strong scientific backing and conservative fishing practices together with international collaboration provide additional support to sustainable management of this fishery. Although North Pacific albacore faces new challenges from climate variability and changing fishing dynamics, with continuous improvements in science, monitoring, and policy coordination, this fishery can remain a model of sustainable ocean governance for years to come.

Click HERE for an extended summary.

Explore Further

- Defining the stock structures of commercial Pacific species to improve advice for fisheries management

- North Pacific Albacore Stock Status and Conservation Information (ISC)

- 2024 Overview of Tuna and Billfish Stocks in the North Pacific Ocean

- The Tuna Fishery in the Eastern Pacific Ocean in 2024

- Overview of Western and Central Pacific Ocean (WCPO) fisheries

- Report of the ISC Albacore Working Group (2025)

- Stock Assessment of Albacore in the North Pacific Ocean in 2023 (ISC)

- Memorandum of Understanding between the WCPFC and ISC

South Pacific Albacore Tuna

| Stock Status | Stock is not overfished and overfishing is not occurring |

| Main Fishery Participants | American Samoa, Cook Islands, Fiji, French Polynesia, Kiribati, New Caledonia, PNG, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu, and Vanuatu, operating primarily in subtropical waters. China and Chinese-Taipei are also active below 20°S. |

Image

| 2024 Catch Volume in the WCPFC Convention Area | 74,591 metric tonnes |

Image

| 2024 Catch Value | US$292 million |

All data is current as of 1 January 2026. | ||

🐟 Understanding the Stock

Albacore tuna (Thunnus alalunga) is one species, but fisheries scientists treat the North Pacific and South Pacific populations as two distinct management stocks. Why? Because oceanographic barriers, unique migration routes, and limited mixing make them functionally separate.

Each stock’s specific biology, such as growth, spawning, and movement, is factored into assessments, allowing targeted, science-based management to ensure long-term sustainability.

🌊 Shared Stewardship Across the Pacific

Management of albacore tuna is a joint effort between the IATTC in the Eastern Pacific Ocean and the WCPFC for the Western and Central Pacific Ocean.

In 2025, both RFMOs agreed to establish a Joint Working Group for management of the South Pacific albacore tuna fishery, a step toward Pacific-wide coordination of this vital fishery.

South Pacific albacore stock assessments for the WCPFC are conducted by the Pacific Community (SPC), the WCPFC’s Scientific Services Provider. The most recent assessment was completed in 2024.

⚖️ Current Fishery Status

The South Pacific albacore tuna stock in the WCPO is in good shape overall: recent scientific advice indicates it is not overfished and not experiencing overfishing, meaning the population is above key biological safety limits and current fishing pressure is still below levels expected to drive the stock down.

At the same time, the fishery is busy and economically sensitive: catches remain high and dominated by longline fleets, recent effort has increased compared with the prior year, and catch rates vary by fleet and area, so some operators feel squeezed even when the stock is healthy.

Management is shifting toward a more predictable “harvest strategy/management procedure” approach, following the adoption of a management procedure in December 2025, to set annual catch levels and keep the fishery within agreed biological bounds while aiming for better stability.

🧭 A Major Milestone

At its 22nd Regular Session in Manila, the WCPFC achieved a landmark outcome with the adoption of the South Pacific albacore management procedure. This decision marked a major advance in modern, science-based fisheries management and reflects years of collective effort by members, scientists, and stakeholders across the region.

The adoption builds on a long history of work by the Commission to develop harvest strategies for key fisheries. For South Pacific albacore, extensive scientific analysis, management strategy evaluation, and rigorous testing were undertaken over several years to ensure the procedure is robust, precautionary, and fit for purpose. This process relied on close collaboration between members engaging through the Scientific Committee, the Commission, and intersessional work, demonstrating the strength of WCPFC’s cooperative approach to regional fisheries governance.

With this adoption, the Commission moves closer to a comprehensive suite of harvest strategies for its major fisheries. The South Pacific albacore management procedure strengthens sustainability, enhances predictability, and reinforces confidence in the Commission’s decisions, demonstrating strong regional leadership and a shared commitment to delivering enduring benefits for present and future generations.

What does the MP do?

Establishes a clear and transparent rule set that links stock status directly to future catch and effort limits.

Why is it important?

Reduces uncertainty and avoids ad hoc management changes, providing greater stability for longline fleets, increased certainty for coastal States and industry players, and a predictable framework for decision-making.

🔬 Why This Fishery Matters

Stock Assessments Show Stability

The South Pacific albacore population has remained fairly stable since the mid-1970s, despite an early decline. Key highlights:

Adult fish catch rates are up, especially in the east

Juvenile fish are being harvested at low levels

Young fish recruitment has increased since the late 1990s

Today, the stock is:

Above sustainable population thresholds

Below critical fishing pressure levels

Close to the interim management target

These findings match the 2024 assessment: the stock is healthy and sustainable.

🧠 Scientific Advice and Management Goals

WCPFC’s interim target is to maintain albacore at 50% of its unfished level. As of 2024, the stock is near this target.

The WCPFC's Scientific Committee supports:

- Maintaining the current target

- Avoiding increases in fishing pressure

- Developing a harvest strategy with clear decision rules

- Ensuring equitable access, particularly for Pacific Island countries

🧩 WCPFC’s Current Management Framework

The current conservation and management measure is CMM 2015-02, following earlier versions from 2005 and 2010.

Key Features:

- Vessel freeze south of 20°S: Most CCMs must keep their number of vessels fishing for South Pacific albacore at or below 2005 (or 2000–2004 average) levels.

- SIDS Flexibility: Small Island Developing States can still develop their domestic fleets.

- Annual Reporting: Vessel numbers and catch (including associated species) must be reported each year.

Reporting Evolution:

- Historical data from 2006–2014 was mandatory; annual updates continue

- Earlier data encouraged for trend analysis

- Review and updates are annual, based on Scientific Committee guidance

With the 2025 adoption of a management procedure for this stock, the Commission will turn its efforts in 2026 toward developing an implementing measure to replace CMM 2015-02.

⚠️ Emerging Management Challenges

Although vessel numbers are capped, fishing intensity is growing:

- 2024 saw 8% catch increase from 2023

- Total albacore catch rose to 74,591 tonnes, mostly via longline catch

- Troll vessel catch also increased by 25%

- High seas fishing now accounts for 23% of longline effort

Fleet-Specific Catch Changes (2024):

- Japan: +64%

- Fiji: +25%

- Chinese Taipei: +23%

- China: –16%

Transhipments are seasonally concentrated (peaking around September), and continue to trend upward.

🧭 What the 2024 Assessment Tells Us

The breeding population stands at ~48% of unfished size, well above the 20% danger zone, and just under the 50% interim target.

The fishery is not overfished, and overfishing is not occurring.

Two Warning Signals:

- Effort Creep: More hooks and advanced tech are increasing actual pressure on the stock.

- Geographic Shift: Concentrated fishing in "hotspots" may stress local populations even as the wider stock looks stable.

🧭 Summary

WCPFC's Scientific Committee recommends aiming to keep tuna populations at about 42–56% of what they would be with no fishing, trying out different targets to see what works best. They also want clear, automatic rules that can limit how much fishing happens (either by reducing catch or effort), and better monitoring of where fish are moving, not just how many boats are out. The current rule (CMM 2015-02) still works, but to protect the fishery and the livelihoods of Pacific Island communities we’ll need management that can quickly respond to changing fish patterns and conditions.

Click HERE for an extended summary.

Explore Further

- The western and central Pacific tuna fishery: 2024 overview and status of stocks

- Summary Report of the 20th Scientific Committee, with the latest scientific advice on South Pacific albacore

- Trends in the South Pacific albacore longline and troll fisheries (as of 25 July 2025)

- Overview of tuna fisheries in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean, including economic conditions – 2024

- Defining the stock structures of commercial Pacific species to improve advice for fisheries management

- WCPFC Harvest Strategy Framework

Skipjack Tuna

| Stock Status | Stock is not overfished and overfishing is not occurring |

| Main Fishery Participants | China, Chinese-Taipei, Cook Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Japan, Kiribati, Korea, Marshall Islands, Nauru, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Tuvalu, United States, and Vanuatu |

Image

| 2024 Catch Volume in the WCPFC Convention Area | 2,045,720 metric tonnes |

Image

| 2024 Catch Value | US$2.7 billion |

All data is current as of 1 January 2026. | ||

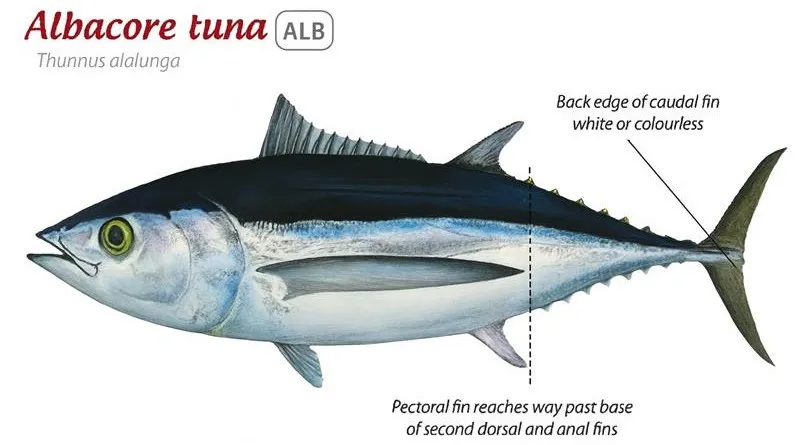

🐟 Understanding the Stock

Skipjack tuna is not managed as a single global stock. Each ocean basin treats skipjack as a separate population, due to limited mixing between oceans. In the Pacific, the Western and Central Pacific Ocean (WCPO) is assessed and managed as one stock with regional sub-zones. The Eastern Pacific Ocean (EPO) is managed separately by IATTC, with cooperation in the overlap area.

This ocean-specific approach reflects differences in fishing fleets, methods, and environmental conditions such as El Niño/La Niña. Most skipjack catch in the WCPO occurs in Pacific Island EEZs, so regional management is tailored to local realities.

🌊 The role of PNA in Skipjack Management in the WCPO

The Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA) are central to the management of skipjack tuna in the western and central Pacific. These eight Pacific Island countries are Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, Nauru, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, and Tuvalu, plus the territory of Tokelau. Collectively, this grouping controls the vast majority of the waters where skipjack purse seine fishing occurs. In fact, most of the region’s skipjack catch is taken within their Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs).

Because of this, the PNA have direct influence over where and how purse seine vessels operate, and their policies shape much of the practical management of the fishery. Their Vessel Day Scheme (VDS) regulates purse seine effort through tradable fishing days, helping ensure sustainability while also generating significant economic benefits for member countries.

In short, the PNA are not only key players; they are essential custodians of the world’s largest skipjack fishery.

🎣 Current Fishery Status (2024)

Total skipjack catch: 2 million mt (a new record), ~67% of all tuna in the WCPFC area.

Purse seine catch: 1.72 million mt, about 84% of total skipjack catch in WCPFC area.

Most WCPO tuna (~88%) is caught in EEZs of coastal States, not the high seas.

In 2024, there was a shift toward free school sets, which helped boost skipjack catch and lower bigeye catch by purse seiners

Key fleets: Japan, Korea, Chinese Taipei, USA, Pacific Islands, plus others like China, Ecuador, El Salvador, New Zealand, Spain (EU).

💰 Economic Importance

Skipjack is the backbone of the WCPO tuna fishery. In 2024, the WCPO contributed ~56% of global tuna catch and ~85% of Pacific-wide tuna. Skipjack’s delivered value was US$3.2 billion (up 8% from 2023).

The fishery is vital to Pacific Island economies, supporting government revenue, employment, and onshore processing investments

🔬 Science

Stock Status (2025 Assessment)

The WCPO skipjack stock is in good condition:

Spawning biomass ≈ 51% of unfished level (well above the 20% safety line).

Fishing pressure ≈ 35% of the sustainable maximum (F/FMSY ≈ 0.35).

Both biomass and fishing pressure have been stable since ~2010.

Stock sits at 98% of the target level (TRP), right where managers aim to keep it.

The 2025 assessment used improved methods, including:

Better modeling of natural death rates

Corrections for pole-and-line "data creep"

Improved treatment of tagged fish data

Scientific Advice to Managers

The Management Procedure (MP) run in 2023 advised:

No change to fishing levels for 2024–2026

Maintain:

Purse seine effort at ~2012 levels

Pole-and-line catch at 2001–2004 average

East Asia domestic catches at 2016–2018 average

Future improvements recommended:

More accurate data on how fast skipjack grow and their age structure

Better understanding of tagged fish movement and tag recovery

Stronger catch and size data from East Asia

Less reliance on pole-and-line catch rates where the fishery has shrunk

🛠️ WCPFC's Management Framework

Key Features

WCPFC uses two main tools:

Management Procedure (MP) with key thresholds:

Limit Reference Point (LRP): 20% of unfished spawning biomass

Target Reference Point (TRP): 50% (aim zone)

Harvest Control Rule (HCR):

Adjusts fishing effort every 3 years

Uses a single “multiplier” to increase, decrease, or maintain effort

Changes limited to ±10% to keep things stable for fleets

Skipjack is also managed under the multi-species Tropical Tuna Measure (CMM 2023-01), including:

FAD closure from July 1 to August 15 (EEZs & high seas)

An additional high seas FAD closure month (per flag)

Non-entangling FADs for all new deployments (since Jan 2024)

A decision on biodegradable FADs due by 2026

Buoy limit: max 350 activated instrumented buoys per vessel

Effort limits by zone (EEZs) and caps on high seas for non-SIDS

Management Issues

Species mix vs. fishing method:

More free school fishing boosted skipjack and reduced bigeye in 2024 — a good result, but future fishing practices must stay aligned with skipjack goals without hurting other stocks.

Environmental variability: Ocean conditions like El Niño/La Niña shift skipjack distribution, so rules must work across changing fishing patterns.

Data quality: The 2025 assessment confirmed the need to improve growth/age data, refine how tag data is treated, strengthen East Asia data, and reduce over-reliance on pole-and-line data in some areas.

FAD management: While non-entangling FADs are now required, big decisions are coming such as the requirement to use biodegradable FADs, a review of the 350-buoy limit, and better tracking and retrieval of lost FADs.

Economic conditions: Overall tuna value fell in 2024, but skipjack value rose. This reinforces the importance of a stable harvest strategy that keeps the stock near its TRP while cushioning against market shifts.

📈 Looking Ahead: Improving Future Management

Stay on track with the Management Procedure:

The next cycle runs in 2026 to set measures for 2027–2029

The ±10% adjustment rule helps avoid sudden changes

Deliver the CMM 2023-01 milestones:

Decision on biodegradable FADs

Review of the 350 buoy cap

Support for FAD retrieval programs

Act on science priorities from the 2025 assessment:

Continue research on growth and ageing

Improve methods for tagged fish data

Strengthen East Asia data inputs

These steps will help ensure confidence in the 2026 MP cycle and keep skipjack fluctuating around the target with low risk of breaching the limit.

🧾 Summary

- 2024 set a record catch for skipjack, reaffirming its role as the economic engine of WCPO tuna, and the 2025 assessment shows the stock is healthy and near target.

- The skipjack Management Procedure advises holding fishing at baseline levels while focusing on improving a few key data inputs and finalizing decisions on FAD management by 2026.

Together, these efforts will keep skipjack tuna sustainably managed for the benefit of all stakeholders well into the future.

Click HERE for an extended summary.

Explore Further

- WCPO 2025 Skipjack stock assessment

- Overview of tuna fisheries in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean, including economic conditions – 2024

- The western and central Pacific tuna fishery: 2024 overview and status of stocks

- CMM 2023-01 - Conservation and Management Measure for Bigeye, Yellowfin and Skipjack Tuna in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean

- CMM 2022-01 - Conservation and Management Measure on a Management Procedure for WCPO Skipjack Tuna

- CMM 2009-02 - Conservation and Management Measure on the Application of High Seas FAD Closures and Catch Retention

- WCPFC Skipjack tuna monitoring strategy report

- Estimates of annual catches in the WCPFC statistical area

Yellowfin Tuna

| Stock Status | Stock is not overfished and overfishing is not occurring |

| Main Fishery Participants | China, Federated States of Micronesia, Guam, Indonesia, Japan, Philippines, Korea, Marshall Islands, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Chinese-Taipei, Vanuatu, and Vietnam. |

Image

| 2024 Catch Volume in the WCPFC Convention Area | 741,473 metric tonnes |

Image

| 2024 Catch Value | US$1.6 billion |

All data is current as of 1 January 2026. | ||

🐟Understanding the stock

Yellowfin tuna is assessed and managed as a single stock across the Western and Central Pacific Ocean (WCPO). This reflects the species’ wide-ranging distribution and higher levels of mixing compared to skipjack. The WCPO stock is distinct from yellowfin in the Eastern Pacific Ocean (EPO), which is managed separately by the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC), with coordination in areas where fisheries overlap.

This basin-wide approach recognizes that yellowfin is targeted by a diversity of fleets and gears, from industrial purse seine and longline vessels to small-scale fisheries in Southeast Asia. Environmental conditions such as El Niño and La Niña events influence catch patterns, with larger fish more common in El Niño years. Most yellowfin catches in the WCPO occur within Pacific Island EEZs, making regional management essential to balance conservation, small island state development aspirations, and the needs of distant-water fishing nations.

Current Fishery Status

- Catch volume: 2024 YFT catch = 741,473 mt (24% of total tuna catch in WCPFC area).

- Gears: Purse seine (~376k mt), longline (~89k mt), plus small-scale fleets in Indonesia, Philippines, Vietnam.

- Fleet dynamics: Pacific Islands purse seiners are growing; other fleets include Japan, Korea, Chinese Taipei, and the United States.

- Trends: Purse seine catches fluctuate; larger YFT appear more in El Niño years.

Economic Importance of the Fishery

- Value: ~USD$1.6B landed value in 2024.

- Markets: Cannery (purse seine) + sashimi/fresh-frozen (longline).

- Food security: Essential in SE Asia & Pacific coastal communities.

📉 Science

Stock Status (2023 Assessment)

- Healthy stock: Not overfished; no overfishing (latest data is from 2023).

- Spatial issues: Localized depletion of big YFT in equatorial purse seine zones.

- Uncertainty drivers: Catch data (esp. SE Asia), growth & maturity assumptions, effort creep.

Scientific Advice to Managers

- Keep fishing mortality at/below current levels.

- Improve catch data & observer coverage (Indonesia, Philippines).

- Improve data that is going into stock assessments.

🎯 WCPFC Management Framework

Key Features

- Objective: Keep spawning biomass ratio (SB/SBF=0) above the average levels from 2012–2015.

- Purse seine controls:

- 1.5-month FAD closure (Jul–mid-Aug)

- +1-month high seas FAD closure

- Non-entangling/biodegradable FADs

- 350 active buoy limit

- Effort/catch limits: Zone-based (PS), longline (zone/flag based), high seas–EEZ compatibility.

Management Challenges

- Mixed-stock fishery (YFT–SKJ–BET) complicates measures.

- Data gaps in SE Asia.

- Equity concerns for SIDS.

- Effort creep with tech advances.

Future improvements

- Adopt Target Reference Point (TRP) & harvest control rules.

- Use new science (effort creep studies, e-monitoring).

- Explore spatial measures for regional depletion.

- Integrate climate resilience into planning.

✅ Summary

Yellowfin remains healthy at the stock level, supporting a high-value fishery. But local depletion, data quality, and equity issues mean that smarter management is needed, through harvest strategies, stronger science, and regionally adapted measures.

Click HERE for an extended summary.

Explore Further

- Overview of tuna fisheries in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean, including economic conditions – 2024

- The western and central Pacific tuna fishery: 2024 overview and status of stocks

- Stock assessment of yellowfin tuna in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean: 2023

- CMM 2023-01 - Conservation and Management Measure for Bigeye, Yellowfin and Skipjack Tuna in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean

- Estimates of annual catches in the WCPFC statistical area

Bigeye Tuna

| Stock Status | Stock is not overfished and overfishing is not occurring |

| Main Fishery Participants | China, FSM, Japan, Korea, Marshall Islands, Chinese-Taipei, United States, Vanuatu |

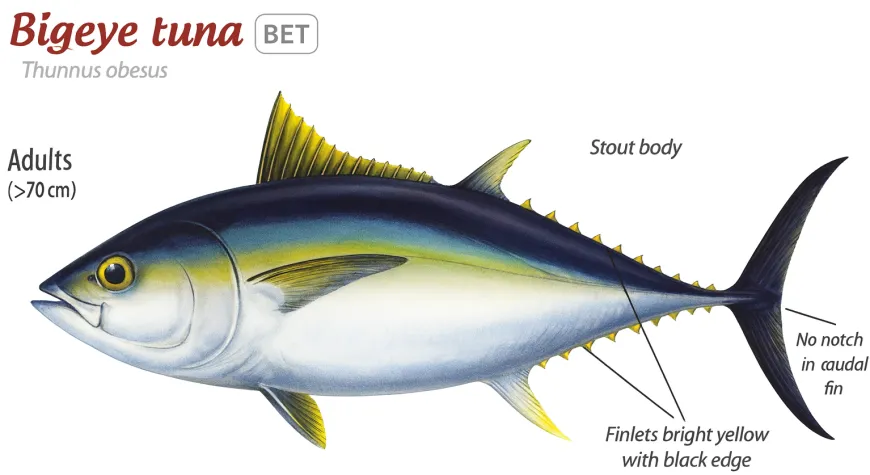

Image

| 2024 Catch Volume in the WCPFC Convention Area | 151,611 metric tonnes |

Image

| 2024 Catch Value | US$508 million |

| All data is current as of 1 January 2026. Sources: Overview of tuna fisheries in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean, including economic conditions – 2024, The western and central Pacific tuna fishery: 2024 overview and status of stocks | ||

🐟 Understanding the Stock

Bigeye tuna in the WCPO is caught mainly by two industrial gears that target different parts of the population. Longline vessels from fleets such as Japan, China, Korea, and Chinese Taipei focus on deeper‑swimming, larger (adult) fish for the sashimi market. Purse‑seine fleets, many of them Pacific Islands vessels alongside Japan, Korea, Chinese Taipei, and the United States, catch bigeye mostly as juveniles when setting on drifting fish‑aggregating devices (FADs) while targeting skipjack tuna. In Southeast Asia, “other” gears (e.g., handline and ringnet) also take small bigeye around anchored FADs.

- 2024 catch snapshot (~151k tonnes, ~5% of total tuna catch in WCPFC area)

- Purse seine: 33% (lowest since 1990, more free-school fishing)

- Longline: 36% (near multi-decade lows)

Current Fishery Status

- Even at low catch levels, bigeye = high value

- 2024 delivered value: ~US$508 million (down ~25% from 2023 due to softer prices)

- Critical for longline fleets targeting sashimi markets

Importance of the Fishery

- ~US$508m ≈ 9% of total WCPO tuna value

- Bigeye (BET) historically fetches the highest sashimi prices on Japanese market

- Economically pivotal despite lower catch volumes

🔬 Science

Stock Status (2023 Assessment)

- Not overfished and not experiencing overfishing

- Breeding potential ≈ 35% of unfished stock

- Above Commission’s limit reference point (20%)

- Meets interim objective (≥ 2012–15 level, ~34%)

- Fishing pressure ≈ 60% of level that would cause overfishing

- Long-term trend:

- Depletion ↑ until ~2010, then stabilized

- Juveniles consistently face higher fishing pressure (FAD sets)

Scientific Advice

- Next assessment due 2026 → interim indicators used

- Recent signals:

- Fishing pressure ↑ temporarily (median F/FMSY ≈ 1.67, 91% chance > MSY)

- Biomass still well above limit (only ~2% risk of dropping below)

- Advice: Stay vigilant, don’t confuse indicators with full stock assessment

- Data challenges: species mix in FAD sets still hard to verify → key for estimating catches of juvenile bigeye tuna

🎯 WCPFC's Management Framework

Current Framework (CMM 2023-01)

- Interim objective: keep spawning biomass ≥ 2012–2015 average until harvest strategy adopted

- Purse seine controls:

- Annual FAD closure (1 Jul–15 Aug, 20°N–20°S)

- Extra 1-month high seas FAD closure (chosen month: Apr, May, Nov, or Dec)

- Cap: 350 drifting FAD buoys per vessel

- Transition to biodegradable FADs by 2026

- Longline controls:

- Flag-specific bigeye catch limits

- Monitoring + payback for overages

- Multi-species link: skipjack, yellowfin & bigeye managed together in purse seine operations

Management Issues

- Juvenile mortality from FAD sets

- Effectiveness of closures, buoy caps, and future standards is central

- Data & monitoring gaps

- Longline observer coverage: only ~3–5% → weak verification of compliance

- Mitigation: link higher catch limits to higher EM/observer coverage

- Purse seine: EM + reporting standards improving after COVID dip

- New approaches: cannery receipts, FAD logbooks for species composition data

Improving Future Management

- Moving toward harvest strategies (rules that auto-adjust fishing)

- To finalize:

- Target reference point

- Management procedure that balances skipjack, yellowfin, bigeye interactions

- Short-term advice:

- Keep fishing pressure ≈ current levels

- Be cautious with capacity increases (models show risk if pushed too far)

- In 2026:

- Lock in high seas limits (purse seine)

- Update longline catch limits

- Strengthen tracking, reporting, auditing of FAD use

- Full shift to biodegradable FADs

✅ Summary

The WCPO bigeye tuna stock is in good biological shape (2023 assessment) but risks remain in the estimation of catches of juvenile bigeye tuna in the purse seine fishery FAD sets as well as low monitoring coverage in the longline fishery. Priorities going forward need to focus on strengthening controls in the purse seine and longline fisheries, delivering on the commitments scheduled in 2026 relating to high seas purse seine effort limits and FAD reforms, and advance the harvest strategy for bigeye tuna. These efforts are expected to maintain stock health while preserving value for fleets and Pacific Island economies.

Click HERE for an extended summary.

Explore Further

- Overview of tuna fisheries in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean, including economic conditions – 2024

- The western and central Pacific tuna fishery: 2024 overview and status of stocks

- Stock assessment of bigeye tuna in the western and central Pacific Ocean: 2023

- CMM 2023-01 - Conservation and Management Measure for Bigeye, Yellowfin and Skipjack Tuna in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean

- Estimates of Annual Catches in the WCPFC Statistical Area (2025)

Pacific Bluefin Tuna

| Stock Status | Stock is not overfished and overfishing is not occurring |

| Main Fishery Participants | Japan, Korea, Chinese Taipei, United States, Mexico |

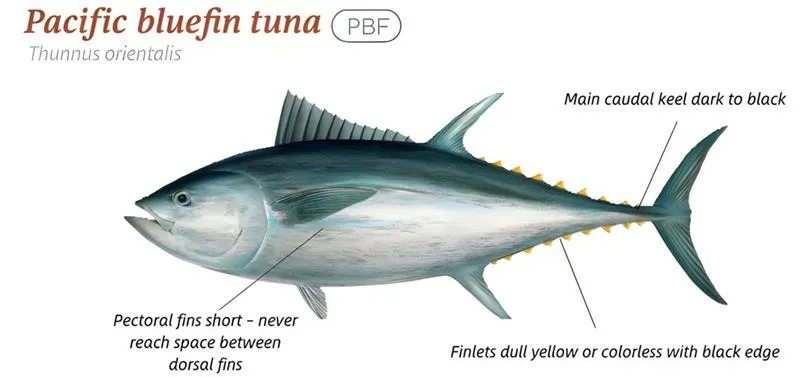

Image

| 2024 Catch Volume in the WCPFC Convention Area | 17,843 metric tonnes |

| All data is current as of 1 January 2026. Source: REPORT OF THE TWENTY-FIFTH MEETING OF THE INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE FOR TUNA AND TUNA-LIKE SPECIES IN THE NORTH PACIFIC OCEAN, 2025; ISC25 Catch Tables, 2024 Overview of Tuna and Billfish Stocks in the North Pacific Ocean | ||

🐟Understanding the stock

There is one stock of Pacific bluefin tuna (PBF) across the Pacific that spawns only in the western North Pacific (Sea of Japan). Many juveniles swim east to feed, then return west to mature and spawn, so the WCPFC and the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC) coordinate closely in management of PBF. After a historic low around 2010, the 2024 assessment estimates the PBF breeding biomass (SSB) reached 23.2% of the unfished level in 2022 (~144,000 t) and already met the 20% rebuilding target in 2021. Protection of small fish (ages 0–3) has been a big driver of recovery.

In the WCPFC, management of the Pacific bluefin tuna fishery is led by the Northern Committee. Scientific advice in relation to this stock is provided by the International Scientific Committee for Tuna and Tuna-like Species in the North Pacific Ocean.

Current fishery status

Who’s fishing where. In the west & central Pacific, key fleets are Japan, Republic of Korea, Chinese Taipei; in the east, Mexico and the United States. Purse-seine fleets take most of the catch; longline and coastal gears generally take larger fish.

Where the impact falls. In 2022, about 83% of total stock impact came from western Pacific fleets and 17% from the east, which is especially sensitive when more juveniles are taken.

Recent activity (context). Members of the International Scientific Committee (ISC) reported ~17,843 t of retained + released PBF in 2024 (not provisional), consistent with controlled catches during rebuilding.

Importance of the fishery

High-value fishery. PBF supports industrial, coastal, and recreational fisheries (including ranching/farming) across the North Pacific. To protect market integrity and value, WCPFC requires stronger monitoring (including farming) and is developing a Catch Documentation Scheme (CDS) to block illegally-caught products.

📉 Science

Stock status: what the latest assessment says (2024)

Status today. The stock is not overfished relative to the 20%SSB reference used for other tunas and not subject to overfishing relative to common F-based benchmarks. Fishing intensity has dropped markedly since the 2000s.

Recruitment signals. Modelled recruitment for 2019–2021 is on the low side, but a standardized Japanese troll index indicates relatively strong recruitment in 2021–2023, aligning with observed biomass growth.

Scientific advice to managers

Room for cautious growth. Some catch increases are possible while keeping SSB above the 20% target with ~60% probability, if increases are carefully distributed (area & size) and current rules are fully implemented. Risk rises if juvenile catch grows.

MSE insights (2025). The ISC tested 16 harvest control rules (HCRs) under alternative productivity scenarios and two WCPO:EPO impact balances (80:20 and 70:30). Many HCRs meet safety objectives; a ±25% cap on TAC changes smooths shocks but slows response to rapid ups/downs. Removing a few simulated assessment “outliers” did not change the relative ranking of HCRs. Robustness tests showed reasonable performance under “effort creep” and doubled discards; a sharp, temporary recruitment dip forces TAC cuts before recovery.

📜WCPFC’s current management framework

Conservation and Management Measure for Pacific Bluefin Tuna (CMM 2024-01).

Keep effort north of 20°N below 2002–2004 levels.

Size-based annual catch limits (<30 kg “small”, ≥30 kg “large”) for Japan, Korea, Chinese Taipei—e.g., Japan: 4,407 t small; 8,421 t large.

Carry-over up to 17% of unused quota; allow one-way transfer from small→large using a 0.68 factor (no transfer the other way).

Tight reporting (including discards), juvenile catch reduction, stronger monitoring of fisheries & farming, progress on CDS, and WCPFC–IATTC coordination; 2026 review using the new assessment & MSE.

Key management issues

Sharing the impact fairly. Western fleets account for the majority of stock impact (~83% in 2022). Choosing—and sticking to—an agreed WCPO:EPO balance (e.g., 80:20 or 70:30) is central for equity and effectiveness.

Juveniles vs adults. Catching many juveniles hurts future spawning more than taking the same weight of adults—hence size-based limits and the one-way small→large transfer.

Implementation realities. The ±25% TAC-change cap aids stability but can lag real-time shifts; discard mortality is uncertain and not fully modelled; climate variability/change needs deeper integration into advice.

Improving future management

Lock in a long-term harvest strategy. Adopt a transparent HCR with agreed reference points, tuned to the chosen WCPO:EPO impact ratio, and paired with predictable TAC-change rules so businesses can plan.

Keep protecting small fish. Use permitted small→large transfers judiciously to align catch with biology.

Upgrade data & monitoring. Timely catch/size data (including discards), reliable recruitment and adult indices, stronger monitoring of fisheries & farming, and a functioning CDS will keep assessments—and a future management procedure—robust.

Be ready to adjust. If recruitment dips, short-term TAC cuts are the right response to stay on track—an expectation normalized by the MSE testing.

✅ Summary

Good news: PBF has rebounded strongly; the stock is above the 20% rebuilding target with fishing pressure compatible with sustainable management.

Stay disciplined: Measured catch growth is feasible only with a durable harvest strategy that keeps juveniles protected, shares impact fairly between west and east, and reacts when recruitment weakens.

Next steps (near-term): Choose an HCR, set the WCPO:EPO impact balance, agree TAC-change rules, and finish CDS/monitoring upgrades. That keeps the fishery reliable and profitable while the stock stays healthy.

Click HERE for an extended summary.

Explore Further

- CMM 2024-01 - Conservation and Management Measure for Pacific Bluefin Tuna

- Stock Assessment of Pacific Bluefin Tuna in the Pacific Ocean in 2024

- 2024 Overview of Tuna and Billfish Stocks in the North Pacific Ocean

- Report of the PBFWG Intersessional Workshop (14-18 April 2025)

- Report of the PBFWG MSE evaluation

- Memorandum of Understanding between the WCPFC and ISC

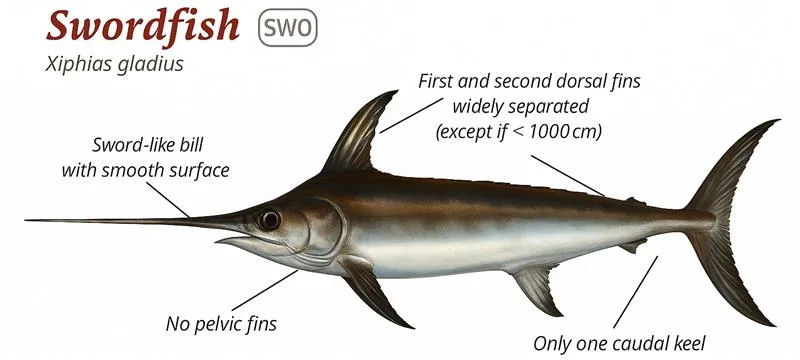

North Pacific Swordfish

| Stock Status | Overfishing is not occurring and the stock is not overfished |

| Main Fishery Participants | Japan, Korea, Chinese-Taipei, United States, Vanuatu |

Image

| 2024 Catch Volume in the WCPFC Convention Area | 8,073 metric tonnes |

| All data is current as of 1 January 2026. Source: Report of the twenty-fifth meeting of the International Scientific Committee for Tuna and Tuna-like Species in the North Pacific Ocean; ISC25 Annual Catch Table, 2024 Overview of Tuna and Billfish Stocks in the North Pacific Ocean | ||

🐟Understanding the Stock

Stock condition

The stock is in good shape. Spawning biomass in 2021 is estimated at ~35,778 t, roughly 2.2× SSBₘₛᵧ (~16,388 t). Recent fishing pressure (F ≈ 0.09 for ages 1–10, 2019–2021) is about half of Fₘₛᵧ (~0.18). The status (Kobe) plot places recent years solidly in the “not overfished / no overfishing” quadrant, with >99% probability for both findings.

In the WCPFC, management of swordfish in the North Pacific is led by the Northern Committee. Scientific advice for this stock is provided by the International Scientific Committee for Tuna and Tuna-like Species in the North Pacific Ocean.

Current fishery status

Catch is dominated by longline fleets across the basin. Annual catch peaked near 19,230 t in 1998 and has stabilized at ~10–12 thousand t in recent years (2019–2021 average ~10,653 t). Catch‑per‑unit‑effort generally improved over the last decade, consistent with a stable to slightly increasing stock.

Importance of the fishery

This is a multi‑national, basin‑wide fishery prosecuted by fleets from Japan, the United States, Chinese Taipei, and others across the WCPFC and IATTC areas; the assessment tracks 19 fleets. That footprint underscores its economic relevance for North Pacific fisheries.

📊Science

Stock status — latest assessment

Using Stock Synthesis (SS3) for 1975–2021, the base case estimates: Fₘₛᵧ ≈ 0.18, SSBₘₛᵧ ≈ 16,388 t, MSY ≈ 14,924 t, and SPRₘₛᵧ ≈ 19%. Recent SPR ≈ 43–44% and F ≈ 0.09 keep the stock comfortably above MSY benchmarks. Probability that the stock is not overfished and not experiencing overfishing is >99%.

Scientific advice to managers

The stock has produced ~11,500 t/yr since 2016 (~two‑thirds of MSY), suggesting capacity for somewhat higher yields depending on risk tolerance. Forward projections to 2031 under a range of constant‑F scenarios keep SSB above SSBₘₛᵧ, including at Fₘₛᵧ; modeled catches converge toward ~15,000 t under higher‑F futures.

Key uncertainties (what to watch)

Two elements drive most uncertainty: (1) lack of sex‑specific size data and (2) a simplified spatial structure in the assessment. Retrospective checks indicate the model may underestimate recent spawning potential—not a status‑changer, but relevant when considering higher fishing pressure.

🏛️ WCPFC management of North Pacific swordfish

Current management framework (CMM 2023‑03)

- Where it applies: High seas and EEZs north of 20° N within the WCPFC Convention Area.

- What it controls: For fisheries taking >200 t/yr, fishing effort must not exceed the 2008–2010 average (with specific notes for the U.S. limited‑entry permits and Chinese Taipei coastal artisanal LL vessel numbers).

- Reporting: CCMs must annually report catch and effort in the Area and across the North Pacific (for fisheries subject to the cap), by gear, recognizing that “fishing days” may not suit bycatch fisheries and allowing for multiple effort metrics.

- Context: WCPFC has adopted a Harvest Strategy establishing a limit reference point for exploitation rate at Fₘₛᵧ (F‑limit = Fₘₛᵧ). The CMM preamble also notes EPO swordfish is not likely overfished but likely experienced overfishing in some recent years, and that stock boundaries are under review, emphasizing cross‑RFMO considerations

✅ Summary

North Pacific swordfish is healthy and stable: SSB ≈ 2.2× SSBₘₛᵧ and F ≈ 0.5× Fₘₛᵧ, with >99% probability of not overfished and no overfishing Under status‑quo F, and even at Fₘₛᵧ, projections keep SSB above SSBₘₛᵧ to 2031 and show catches gravitating toward ~15,000 t if effort increases. What do short‑term policy wins look like? Formalized reference points, tightened key data streams, and strengthened coordination with IATTC for this shared stock.

Click HERE for an extended summary.

Explore Further

- 2024 Overview of Tuna and Billfish Stocks in the North Pacific Ocean

- Stock Assessment Report for Swordfish (Xiphias gladius) in the North Pacific through 2021

- International Committee for Tuna and Tuna-like Species in the North Pacific Ocean (ISC)

- Conservation and Management Measure for North Pacific Swordfish (CMM 2023-03)

Southwest Pacific Swordfish

| Stock Status | Not overfished and overfishing is not occurring. |

| Main Fishery Participants | Australia, European Union (Portugal and Spain), Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Chinese Taipei, United States (Hawaii) |

Image

| 2024 Catch Volume in the WCPFC Convention Area | 17,572 metric tonnes |

| All data is current as of 1 January 2026. Source: Overview of tuna fisheries in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean, including economic conditions – 2024 ; Summary Report of the Seventeenth Regular Session of the WCPFC Scientific Committee (SC17) - 2021. | ||

Understanding the Stock

Stock condition 🟢

Southwest Pacific swordfish are in good health by MSY standards: the median recent spawning biomass is well above the level that would produce MSY (SB_recent/SB_MSY ≈ 2.37), and recent fishing mortality is well below the MSY threshold (F_recent/F_MSY ≈ 0.27). The stock is not overfished and overfishing is not occurring, though biomass has eased back from mid‑2010s highs.

Current fishery status 🎣

This is primarily a longline fishery: targeted fleets operate off eastern Australia and New Zealand, EU‑Spanish vessels fish the central high seas, and there is notable bycatch in the subtropical/tropical northeast of the region. Catches rose through the 2000s (peaking around 9–10 thousand tonnes) and have settled in recent years to roughly 5,000–,6,000 tonnes a year within the assessment area.

Importance of the Fishery 💰

Even though longline makes up only a small share of total WCPO tuna/billfish catch by volume (∼8–10%), it punches above its weight in value, supporting domestic fleets and access revenues across the Pacific. WCPFC has also flagged South Pacific swordfish as a source of long‑term economic opportunity for small island developing states when well managed.

Science

Stock status – latest assessment 🔬

The 2025 benchmark assessment moved to Stock Synthesis, adopted a two‑sex model, and explored a 360‑model uncertainty grid. Across that ensemble, the headline remains robust: green‑zone on both biomass and fishing pressure (see ratios above), with key uncertainties in growth, absolute population scale, and spatial structure.

Scientific advice to managers 🧭

Keep harvests within the current envelope, but strengthen the evidence base: prioritize Close‑Kin Mark‑Recapture (CKMR) to validate population size; expand age‑reading programs; standardize length/weight measurements; and continue CPUE diagnostics so abundance indices are resilient to gear/behavioral effects.

How does the WCPFC manage the Southwest Pacific swordfish fishery?

Current management framework 🏛️

WCPFC’s measure CMM 2009‑03 caps each member’s number of swordfish vessels and total catch south of 20°S at historical maxima (2000–2005 for vessels; 2000–2006 for catch), forbids shifting effort north of 20°S to compensate, requires catch nominations and annual reporting, recognizes SIDS development aspirations, and sets up compliance review. The measure also acknowledges the need to coordinate with IATTC.

Management issues ⚠️

- Geography vs biology. The control line at 20°S misses substantial fishing and movement north of that boundary; swordfish mix across broad areas, including the eastern high seas.

- Cross‑RFMO fit. A large share of South Pacific swordfish is taken where WCPFC and IATTC responsibilities meet—policy coherence matters.

- Information gaps. Growth and population scale remain uncertain; conflicts between some CPUE signals and size/weight data highlight the need for standardized measurements and stronger composition datasets.

Improving Future Management 🔧

- Adopt a harvest‑strategy framework (targets, limits, monitoring, and pre‑agreed harvest control rules) tailored to this stock, including formal reference points.

- Modernize spatial controls so limits reflect where fish and fisheries actually operate (including north of 20°S), with joint work with IATTC in the east.

- Invest in pivotal data: implement CKMR, expand sex‑specific ageing, standardize length/weight conversions, and ensure timely size/sex submissions, noting how electronic monitoring can help.

Summary 🧾

Southwest Pacific swordfish is a healthy stock delivering high‑value longline catches. The current cap‑and‑stabilize measure south of 20°S has held the line, but the next step is a harvest‑strategy approach and a tighter science backbone (CKMR, ageing, standardized size data), paired with better spatial alignment and WCPFC‑IATTC coordination. That combination keeps conservation risk low while protecting economic benefits for coastal states.

Click HERE for an extended summary.

North Pacific Striped Marlin

| Stock Status | Overfished; overfishing likely occurring |

| Main Fishery Participants | Japan, Chinese Taipei, USA |

Image

| 2024 Catch Volume in the WCPFC Convention Area | 2,433 metric tonnes |

| All data is current as of 1 January 2026. Sources: Stock Assessment Report for Striped Marlin (Kajikia audax) in the Western and Central North Pacific Ocean through 2020; ISC25 Annual Catch Table, 2024 Overview of Tuna and Billfish Stocks in the North Pacific Ocean | ||

🧭Understanding the Stock

Stock condition

- Status: The stock is overfished and likely experiencing overfishing when judged against both MSY and the Commission’s rebuilding benchmark of 20% of unfished spawning biomass.

• 2020 spawning biomass: ~1,696 t vs. target 3,660 t.

• Recent fishing mortality (2018–2020): ~0.68 yr⁻¹, above the rebuilding level (0.53) and slightly above FMSY (0.63).

Current fishery status

- Catches: High in the late 1970s–1990s (~7,200 t/yr), now ~2,400–2,500 t/yr (2018–2020).

- Fleets & gear: Shift from historical driftnet dominance to modern longline fleets (Japan, Chinese Taipei, U.S., others).

- Recruitment: Two decades of below‑average recruitment have held the stock down despite recent F reductions.

Importance of the fishery

- Mixed longline bycatch across many fleets and EEZs; management choices ripple across tuna/swordfish longline fisheries and supply chains.

🔬 Science

Stock status – latest assessment

Scientific advice for this stock is provided by the International Scientific Committee for Tuna and Tuna-like Species in the North Pacific Ocean.

- Model & period: Stock Synthesis (SS3), 1977–2020.

- Key numbers: Biomass (age 1+) ~7,300 t (2020); SSB ~1,200 t on average during 2011–2020; overfished >99% probability; overfishing likely (>66%).

- Drivers: Persistent low recruitment since ~2000 and catch of immature fish.

- Uncertainty: Growth curve and historical driftnet catches remain big sources of uncertainty.

🧭Scientific advice to managers

- Keep total catch at or below recent levels (2018–2020 average ≈ 2,428 t).

- Under ~2,400 t constant catch, projections show SSB rising above SSBMSY and approaching 20%SSB(F=0) by ~2040 if the recent “low‑recruitment” regime continues; stronger recruitment would speed this.

🏛️ How does the WCPFC manage the North Pacific striped marlin fishery?

Current management framework (CMM 2024‑06)

- Scope: Applies on the high seas and EEZs north of the equator.

- Total catch cap (TAC): 2,400 t per year (2025–2027); if exceeded, automatic review the following year.

- National limits:

• Japan 1,454.4 t • Chinese Taipei 358.4 t • Korea 214.8 t • United States 228.4 t • China 68.8 t (total 2,324.8 t; the remainder covers others within the TAC). - Underage reserve: Unused TAC moves to a shared reserve; each listed CCM may draw up to +165 t when reserve tonnage exists.

• 826 t underage from 2023 is available for 2025; 2024 underage for 2026; 2025 underage for 2027.

• Priority access to the reserve for CCMs whose domestic rules would otherwise shut a target fishery. - When a CCM hits its limit: Prompt live release of striped marlin to maximize post‑release survival (with crew safety).

- Accountability/data: Overages are deducted in the next adjustment year; CCMs must report catch, effort, and live/dead discards and meet improved data requirements no later than 2027.

- Review: Measure replaces CMM 2010‑01 and will be reviewed/amended in 2027 alongside a new ISC assessment.

⚠️ Management issues (from Commission discussions in 2024 and the latest stock assessment)

- Allocation & baselines: Debates on whether limits should reflect older high‑catch baselines (2000–2003) or recent levels (2018–2020) used in rebuilding advice.

- Retention vs. data needs: Non‑retention was discussed but not adopted; the measure instead uses live‑release after limits to maintain landings/discard data for science.

- Science uncertainties: Growth and possible stock mixing across boundaries affect absolute scale and rebuilding metrics; juvenile catch depresses SSB.

- Monitoring: Implementing EM and improving discard reporting are central to making the TAC, live‑release, and overage deductions work in practice.

🔧 Improving Future Management

- Stay at or below the TAC: Holding the fishery near ~2,400 t aligns with ISC advice and the new measure’s rebuilding plan.

- Tighter monitoring & data by 2027: Deliver complete catch + live/dead discards and leverage EM minimum standards to verify longline operations.

- Reduce juvenile mortality: Gear/handling tweaks, spatial or seasonal choices, and prompt live release once limits are reached help protect spawners.

- 2027 stock assessment & review: The Commission will revisit allocations and rebuilding settings using updated science (including improved growth information).

✅ Summary

- The stock is depleted and fishing pressure remains high relative to rebuilding needs.

- ISC says keep total catch ≲ 2,400–2,500 t and improve data; projections at ~2,400 t show the stock climbing above SSBMSY and moving toward 20%SSB(F=0) by ~2040 under conservative recruitment.

- WCPFC has now locked in a 2,400 t TAC (2025–2027) with national limits, a reserve mechanism, live‑release after limits, and stronger reporting/EM—all to be reviewed in 2027 with new science.

Click HERE for an extended summary.

Explore Further

- 2024 Overview of Tuna and Billfish Stocks in the North Pacific Ocean

- WCPFC21 Summary Report (see Attachment S for a Summary of Small Working Group Discussions on NP Striped Marlin, and relevant report sections.)

- Conservation and Management Measure for the North Pacific Striped Marlin (CMM 2024-06)

- ISC 2023 Stock Assessment for WCNPO Striped Marlin through 2020 (latest information on status, reference points, projections, uncertainties)

Southwest Pacific Striped Marlin

| Stock Status | Likely overfished, but unlikely to be undergoing overfishing |

| Main Fishery Participants | Australia, French Polynesia, Japan, New Caledonia, Chinese Taipei |

Image

| 2024 Catch Volume in the WCPFC Convention Area | 4,263 metric tonnes |

| All data is current as of 1 January 2026. Source: 2025 Stock Assessment of Striped Marlin in the Southwest Pacific Ocean: Part II – Bayesian Surplus Production Model (Rev.01); Overview of tuna fisheries in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean, including economic conditions – 2024 | ||

Understanding the Stock

📉Stock condition

- Current status (production‑model view): The Bayesian surplus‑production assessment (1952–2022) indicates the stock is overfished but not currently undergoing overfishing. “Recent” ratios are D/Dₘₛᵧ ≈ 0.77 and F/Fₘₛᵧ ≈ 0.77, with ~74% probability the stock is below Dₘₛᵧ and ~23% probability that overfishing is occurring. Projections at recent catch levels show continued recovery, with the median D/Dₘₛᵧ crossing >1 within ~10 years (≈ 1.32 by 2032).

- Trajectory: Abundance declined from the unfished state to low levels by the mid‑2010s, followed by a sustained rebound since ~2015.

- Cross‑model check (integrated SS3): A revised age‑structured assessment reproduces broad trends but estimates implausibly low absolute biomass, so SB‑based reference points may be overly pessimistic. Use SS3 together with the production model and empirical indices.

🎣Current fishery status

- Fishery footprint: Longline fleets (distant‑water and Pacific Island fleets) take most striped marlin as a valuable byproduct; there is opportunistic targeting (e.g., Australia’s ETBF) and significant recreational fisheries (New Zealand, Australia).

- Effort & removals: Longline effort grew from near zero in the early 1950s to ~100–150 million hooks/yr (1970s–1990s), then to ~350 million around 2003, fluctuating near that level since; total removals have been broadly stable with a slight recent decline.

- Abundance signals: Mixed—several longline indices (e.g., DWFN composite) and some observer‑program indices increased recently; the New Zealand sport index declined; one observer index is flat—reflecting spatial/sector contrasts and index representativeness issues.

💼 Importance of the Fishery

- Economic role: Longline fisheries remain important across the WCPO, but 2024 price declines weakened longline economic indices—conditions that can influence incentives for retention and reporting of byproduct species such as striped marlin.

- Recreation & culture: Striped marlin has a long sport‑fishing history (e.g., New Zealand club records since the 1920s), contributing to coastal economies and data streams.

Science

🧮Stock status — latest assessment

- Data‑moderate BSPM (state‑space production model, 1952–2022): Summarizes status using D and F relative to MSY (not SB); indicates overfished, no overfishing, and continued recovery at recent catches. Status windows: 2019–2022 (depletion) and 2018–2021 (F).

- Integrated SS3 revision (2025): Addresses earlier diagnostics yet still infers very low biomass scale; SB‑based reference points are highly uncertain. Managers should consider multiple models plus empirical CPUE when forming advice.

📌Scientific advice to managers

- Catches: Maintain at or below recent levels to support recovery; ensemble projections at status‑quo catches show rising D/Dₘₛᵧ and low overfishing risk.

- Data priorities: Invest in Close‑Kin Mark–Recapture (CKMR) to anchor absolute abundance; expand age–length (otolith) sampling; advance genetics to clarify stock structure/connectivity.

- Pathway: Embed the stock within a harvest‑strategy framework tested via Management Strategy Evaluation (MSE); as data improve, progress toward age‑structured Bayesian approaches.

How does the WCPFC manage the Southwest Pacific striped marlin fishery?

⚖️Current management framework

- Primary measure—CMM 2006‑04: Caps each CCM’s number of vessels south of 15°S to the level in any one year during 2000–2004; recognizes SIDS/coastal development rights; requires reporting of vessels and catches; TCC monitors compliance; certain coastal states with commercial landing moratoria are exempt from paragraphs 1–4.

🔍Management issues

- Effort cap ≠ mortality cap: Vessel‑number limits are a coarse proxy for fishing mortality and may not track F as technology, deployment, and targeting evolve.

- Data & structure uncertainty: Dominant uncertainties include population scale, early‑period data anomalies, under‑reporting/discards, divergent CPUE signals, and unresolved stock connectivity beyond the assessment region.

- Mixed‑fishery dynamics: Market‑driven changes in tuna targeting can shift striped marlin removals without altering “vessel numbers,” complicating control of F.

🧭Improving Future Management

- Adopt a harvest strategy: Set explicit targets/limits (e.g., D/Dₘₛᵧ or calibrated F‑based rules) and test controls (effort or catch limits; spatial/temporal tools; handling standards) via MSE.

- Strengthen monitoring: Increase longline observer coverage, standardize/diagnose CPUE series (including observer‑based indices), and reconcile early catch/effort anomalies.

- Resolve scale & structure: Prioritize CKMR, genetics, and age–length programs to anchor absolute abundance and life history—directly reducing uncertainty in reference points.

- Review CMM 2006‑04: Update toward controls that act directly on fishing mortality (F‑calibrated effort or catch limits with accountability), nested within the harvest‑strategy pathway.

✅ Summary

- Best current reading (BSPM): Overfished, no overfishing, and recovering at recent catches; median D/Dₘₛᵧ > 1 projected within ~10 years if recent conditions persist.

- Caveat (SS3): Absolute biomass scale is highly uncertain; SB‑based metrics likely too pessimistic—interpret in a multi‑model context alongside empirical indicators.

- Management direction: Presently governed by CMM 2006‑04 (vessel caps south of 15°S). Science supports transitioning to a harvest‑strategy/MSE framework, with stronger monitoring and targeted research (CKMR, growth, M, steepness, genetics) to align controls to F and tighten advice.

Click HERE for an extended summary.

Explore Further

- Revised 2024 stock assessment of striped marlin in the southwestern Pacific Ocean: Part 1- integrated assessment in Stock Synthesis (Rev.03) (SS3)

- 2025 Stock Assessment of Striped Marlin in the Southwest Pacific Ocean: Part II – Bayesian Surplus Production Model (Rev.01)

- Conservation and Management Measure for Striped Marlin in the Southwest Pacific (CMM 2006-04)