🦈 WCPFC Shark Bycatch Mitigation Terms

This guide outlines key measures and tools the WCPFC uses to manage shark bycatch in tuna fisheries. These terms appear in conservation and management measures for sharks and are aimed at reducing shark mortality and improving data collection.

📘 Definitions and Measures

Monofilament Leaders: Use of nylon monofilament line for branch leaders instead of steel wire. Sharks can bite through monofilament to escape, reducing their catch and post-hooking mortality. WCPFC now prohibits wire leaders on longlines to increase the chance that hooked sharks free themselves, thus lowering shark bycatch mortality.

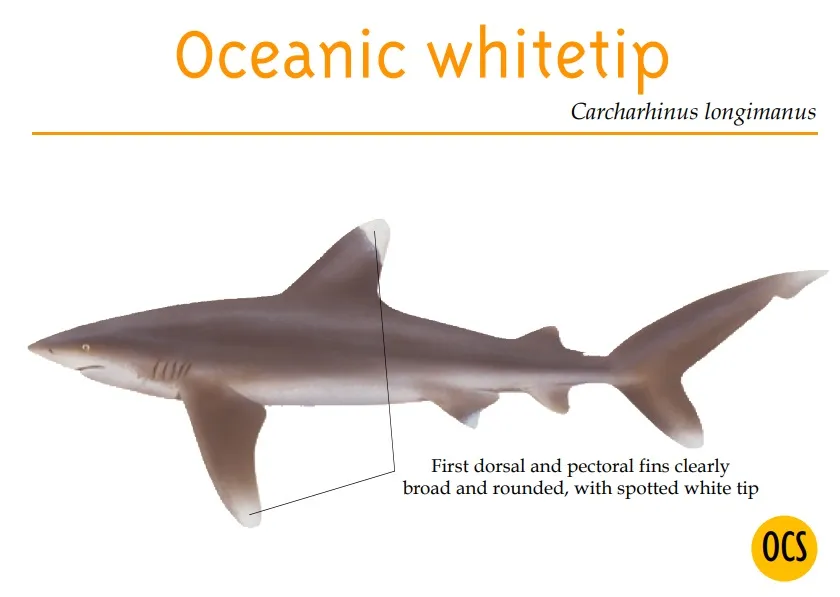

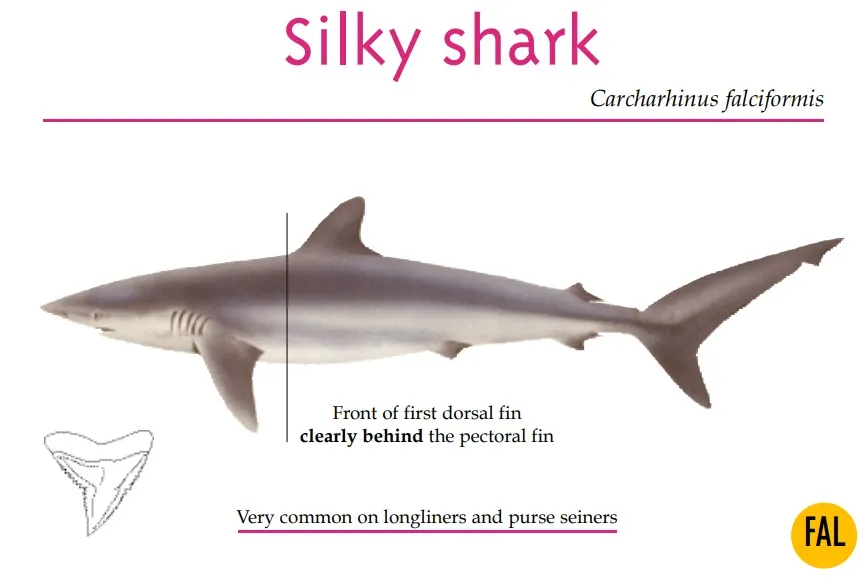

Shark Lines: Specialized drop lines attached near floaters on longlines to target sharks in the upper water column. WCPFC has banned the use of shark lines in tuna fisheries, as these were used to deliberately catch sharks. Removing shark lines forces gear to focus on target species and reduces the overall shark catch, especially of species like silky and oceanic whitetips that often swim near the surface.

Fins Naturally Attached: A policy requiring that sharks retained by fishing vessels be landed with their fins still naturally attached to the carcass. This measure, adopted by WCPFC, ensures compliance with the ban on shark finning (discarding carcasses at sea and keeping only fins) and improves species-specific catch data. Fishermen must now store and offload shark fins only when still attached to the body, promoting full utilization of any shark catch.

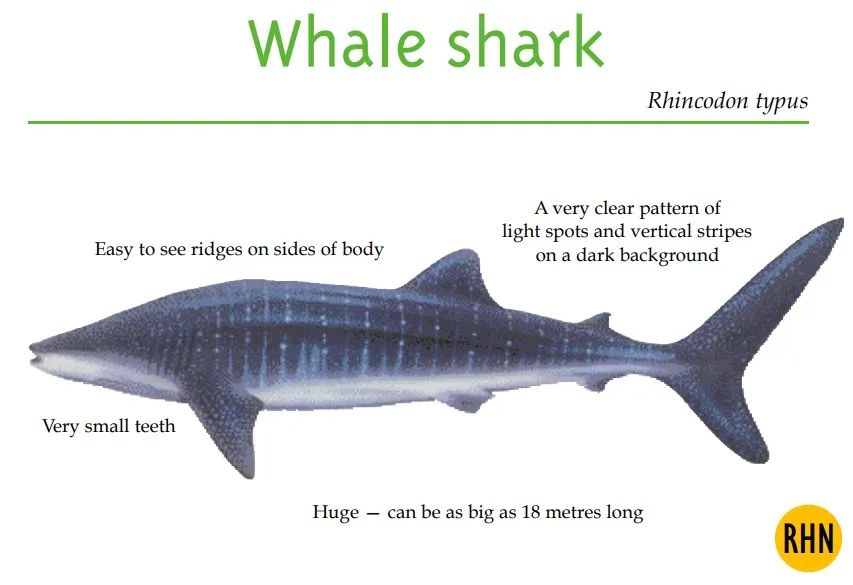

No-Retention Species: Several shark species are designated as no-retention in WCPFC fisheries, meaning they cannot be kept or sold and must be released if caught (dead or alive). Notably, oceanic whitetip sharks and silky sharks are fully protected in this way, as is the whale shark (which is not to be targeted or retained). This policy removes economic incentive to catch these threatened species and emphasizes their release.

Safe Release Guidelines: Protocols and equipment for safely handling and releasing sharks from fishing gear. WCPFC is developing and endorsing guidelines (similar to FAO best practices) for crew to cut lines or gently remove hooks from live sharks (especially the no-retention species) with minimal injury. Tools like long-handled de-hookers, line cutters, and stretchers or slings (for large animals like whale sharks) are part of safe release gear. Training crew in these methods helps improve post-release survival of sharks.

Sharks in the WCPO

This page summarizes the status of key shark species in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean (WCPO) and the bycatch mitigation actions adopted by the WCPFC. Pelagic sharks such as the oceanic whitetip, silky, blue, mako, and thresher sharks, as well as the whale shark (a large filter-feeding species) and hammerhead sharks, are all encountered in WCPFC-managed tuna fisheries. Many of these species have experienced significant declines and are classified as threatened or endangered globally. Incidental catch (and historically, intentional harvest for fins) in longline and purse-seine fisheries has been a major source of mortality for oceanic sharks. WCPFC’s management measures focus on reducing shark interactions and mortality through gear regulations, no-retention policies for the most vulnerable species, and improving handling and reporting practices.

WCPFC has implemented a suite of shark conservation measures across its fisheries. Longline vessels are required to avoid practices that heighten shark catch rates – for example, the use of wire leaders and branch lines targeting sharks is banned, and all vessels must land any retained sharks with fins naturally attached to enforce the finning ban. In purse-seine fisheries, setting nets around whale sharks is prohibited, and any sharks entangled in Fish Aggregating Devices (FADs) or caught in nets should be released alive when possible. Moreover, the Commission has designated certain sharks (oceanic whitetip, silky, etc.) as protected, mandating their release if caught. Through these measures, and ongoing scientific monitoring, WCPFC aims to curb shark bycatch mortality and support the recovery of depleted shark populations while still allowing sustainable tuna fishing operations.

Oceanic Whitetip Shark

Latest assessment | No full recent stock assessment; indicators (2012 WCPFC analysis) showed severe depletion. |

Status | Critically Endangered globally (IUCN 2019). Population in the Pacific estimated to be <10% of historical levels, with continued low abundance. |

Key findings | Once one of the most common oceanic sharks in the tropics, the oceanic whitetip has undergone a dramatic decline in the WCPO. By the 2000s, scientific analyses indicated a drop of over 90% from baseline abundance due to high fishing mortality. This species is caught as bycatch in both longline and purse-seine fisheries – often attracted to baited hooks or aggregating under tuna FADs. Its slow growth and low reproduction (few pups per litter) mean it cannot withstand heavy mortality. Even low interaction rates can be devastating when the population is so depleted. The oceanic whitetip’s large fins made it a historical target of shark finning, which greatly contributed to its collapse. Now, with finning banned and retention prohibited, reported catches have fallen, but ongoing bycatch (and possibly IUU fishing) still hinder recovery. |

Management | WCPFC implemented a no-retention policy for oceanic whitetip sharks in 2011 (CMM 2011-04): all must be released immediately if caught, and no part (fins or meat) may be retained. Vessels are instructed to handle whitetip sharks by cutting the line close to the hook rather than attempting to bring the shark on board, to minimize injury. In addition, the ban on wire leaders and shark lines (effective 2015) is particularly beneficial for oceanic whitetips, as it reduces their catch probability in longlines. Observers or electronic monitors record any interactions; if a whitetip is found dead on retrieval, it still must be discarded (with the incident reported). Some WCPFC member countries have gone further, imposing domestic penalties for any retention of oceanic whitetips to ensure compliance. Overall, the management goal is to reduce mortality to as close to zero as possible, giving this critically endangered shark the best chance to rebuild over time. |

Range and fishery interactions

- Oceanic whitetip sharks are found in warm waters throughout the Pacific, mostly between 30°N and 30°S. They are highly migratory and typically inhabit the upper mixed-layer of the open ocean. This brings them into frequent contact with tuna fishing gear. They often follow scent trails to longline baited hooks set in the top few hundred meters, and they are known to aggregate around FADs (which makes them susceptible to purse-seine bycatch when tuna schools associate with those FADs). Historically, they were a common bycatch in tropical tuna fisheries, but populations have become so reduced that encounters are now relatively rare – a concerning sign in itself.

- Because oceanic whitetips often remain near the surface even in daytime, they were frequently captured by shallow-set longlines and by any intentionally deployed “shark lines.” Even in deeper sets targeting tuna, some whitetips get hooked during setting or hauling when gear is shallower. In purse seines, most interactions occur when juvenile whitetips associating with FADs get entangled in the net or are inadvertently brailed aboard with the tuna catch. These sharks have a high at-vessel mortality rate – they often fight hard when hooked, leading to exhaustion or injury.

Effective bycatch mitigation

- The most direct mitigation is the ban on targeted shark gear: by removing wire leaders and not allowing shark lines, longline fishers effectively decrease the catch of oceanic whitetips (and other sharks). Monofilament leaders give any hooked whitetip a chance to bite off and escape. Early data after these measures suggest fewer whitetips are being landed on compliant vessels, indicating the gear changes are working.

- For purse seiners, avoiding entanglement is key. The adoption of non-entangling FADs – FAD designs without hanging net webbing – prevents many sharks (including oceanic whitetips) from getting ensnared underneath FADs. Crews are also trained to look for sharks (and other species) when a FAD is encircled; if a whitetip is seen in the net, they should release it while it’s still in the water (e.g., using a release chute or lowering a section of the net) rather than hauling it aboard.

- When a whitetip is hooked on a longline, the crew should refrain from gaffing or lifting it onboard (which could injure the shark and crew). Instead, they should cut the line as close to the hook as safely possible, ideally leaving only a short length of leader attached to the shark. Using a long-handled cutter for this purpose keeps crew safe and increases the shark’s chance of survival. Some fleets have also trialed weak hooks (that straighten under big fish like sharks) as a mitigation measure, though this can risk losing target catch as well.

Monitoring and enforcement

- The rarity of oceanic whitetip sightings now means that high observer coverage or electronic monitoring is needed to detect any events and ensure compliance with the no-retention rule. WCPFC is moving toward higher monitoring coverage in longline fleets; 100% observer coverage is already in place for many purse seine vessels, which helps verify that whitetips, if caught, are indeed released and not finned. EM (electronic cameras) can be particularly useful on longliners to document shark handling practices on deck.

- Port inspections and transshipment monitoring are another enforcement tool: authorities check landed tuna catches for any hidden shark fins or carcasses. Because oceanic whitetip fins were historically valuable, there’s risk of illegal retention. Strong penalties (including potential blacklisting of vessels) and cooperation among member countries aim to deter any such violations. WCPFC compliance reports in recent years have noted improved adherence, but also stress continued vigilance.

- Scientists continue to monitor oceanic whitetip recovery (or lack thereof) through fisheries-independent surveys and modeling. They use catch-per-unit-effort (CPUE) trends from observer data as an index of abundance. So far, any signs of population increase are not clear, likely because even minimal ongoing mortality impedes growth of such a depleted stock. Continued protection and further bycatch mitigation innovation (e.g., exploring shark repellents or avoiding certain hot spots) remain priorities for this species.

Source documents: WCPFC stock status assessments (SC8/SC9 analyses); CMM 2011-04 requirements; IATTC & ISC reports on shark declines; IUCN Red List (2019).

Silky Shark

Latest assessment | 2013 Pacific assessment (WCPFC-SC9) indicated overfished status; no newer full assessment. |

Status | Vulnerable globally (IUCN 2017). Still relatively widespread but substantially depleted in parts of its range; slow recovery due to moderate productivity. |

Key findings | Silky sharks are among the most frequently encountered sharks in WCPO tuna fisheries, especially in equatorial waters. They are named for their smooth skin and are a mid-sized, fast-growing shark, but still have a fairly low reproductive rate (giving birth to a dozen or fewer pups annually). Silky sharks often associate with floating objects and tuna schools – meaning they are commonly caught in purse-seine sets around FADs (mostly juvenile silkies) and are also taken in longlines. Prior to regulations, silky shark fins were a significant portion of the shark fin trade from the Pacific, and high catches led to notable declines. Stock analysis last decade showed signs of overfishing, with juveniles being removed at unsustainable rates. Since then, some indicators (such as observer CPUE of juveniles) suggest slight reductions in bycatch due to management measures, but silkies remain depleted compared to historical levels. Their schooling nature around FADs makes them particularly vulnerable to fishing, as multiple individuals can be caught in a single set. |

Management | WCPFC’s no-retention policy for silky sharks came into effect in 2013 (CMM 2013-08). This means vessels must release all silky sharks as soon as they are seen caught, and are not allowed to deliberately target or retain them. Purse seine vessels, in particular, have protocols to release live sharks from the net: for example, using hopper release panels or gently lowering net sections to let sharks swim out. The shift to non-entangling FADs is also crucial for silkies – it prevents many from becoming entangled in FAD tether materials (a historically common cause of mortality for this species). In longline fisheries, the ban on wire leaders helps silkies bite off and escape if hooked. Additionally, some fleets avoid using shark-attracting bait or shallow hooks in areas/time periods known for high silky shark abundance. All catches (whether released alive or found dead) must be recorded; increased training has been given to crews and observers to accurately identify silky sharks (to distinguish them from other similar species). Combined, these measures aim to drastically reduce fishing mortality on silky sharks, giving their populations a chance to rebuild. |

Biology and interactions

- Silky sharks are a tropical and subtropical species, mostly found between 20°N–20°S in the Pacific, often in the upper 200 m of the water column. They have a tendency to aggregate around floating objects (both natural debris and man-made FADs) because these areas concentrate prey. This behavior unfortunately increases their encounter rates with purse-seine gear: when a FAD is encircled for tuna, groups of silky sharks that were underneath can be caught as bycatch. Purse-seine observer data historically showed silky sharks as the most common shark species caught in such sets, especially young sharks of 50–100 cm length. In longline fisheries, silkies (particularly sub-adults and adults) are caught on tuna hooks as bycatch, mostly in shallower sets in tropical waters. They are less hardy than some sharks; a significant fraction caught on longlines are found dead by the time the gear is retrieved.

- In terms of life cycle, silky sharks mature at around 6–10 years of age and can live 20+ years. Their moderate growth and reproduction mean populations can only tolerate low to moderate levels of fishing pressure. In the 1990s and early 2000s, a combination of targeted fishing (for fins) and high bycatch in tuna fisheries caused steep declines in silky shark numbers regionally. Scientists noted declines in standardized catch rates and mean sizes – signs of overexploitation. The species’ Vulnerable listing reflects these global declines, though some regional sub-populations (e.g., in the central Pacific) might be worse off than others.

Mitigation measures for fleets

- Purse seine fleets have been encouraged to adopt shark-friendly practices: avoid deploying FADs in areas during seasons of exceptionally high juvenile silky presence, and monitor FADs for shark activity (via sonar or cameras) so they can decide to skip a set if too many sharks are present. When silkies are caught in the net, crew should prioritize their release. Methods include using a dedicated “shark release net” or canvas sling to lift larger sharks out of the main net and over the side, or opening a portion of the net early. Some vessels have experimented with small meshes or escapement devices that let small sharks slip out during net hauling. Every shark released alive is a small victory for conservation, so crews are instructed on handling do’s and don’ts (e.g., do not gaff or stab sharks, minimize time out of water).

- Longline vessels, besides employing monofilament leaders, can reduce silky shark bycatch by avoiding setting shallow hooks at dusk/dawn in certain areas where silkies are common. Some fishermen report that using fish bait instead of squid might slightly reduce shark bite frequency (sharks are very attracted to squid scent). If a silky is hooked, the best practice is to cut the line promptly. If the shark is small enough and at the surface, some crews will use a de-hooker to flip the hook out without bringing the shark aboard. If the shark is large, it’s safer to cut the line near the hook. These practices improve the odds that the shark survives (studies show many silky sharks can survive if released in good condition).

- National initiatives complement WCPFC rules. For example, some Pacific Island countries have established shark sanctuaries or national prohibitions on shark retention in their EEZs, reinforcing the Commission’s no-retention rule. In those zones, any silky shark caught must be released, and fisheries patrols keep an eye out for illegal finning. Such national laws can apply even to small-scale coastal fisheries, tackling mortality sources beyond just the industrial tuna fleets.

Monitoring and compliance

- Observer coverage in purse seine fisheries (currently near 100% for licensed vessels) has been crucial to monitoring silky shark outcomes. Observers record how many sharks are seen, how many are released alive, and the condition upon release. These data show improved handling in recent years, but also reveal that a large portion of silky sharks caught in FAD sets may be dead before release (due to stress or entanglement). This underscores the need to keep working on preventative measures (like better FAD design and possibly limits on FAD sets in areas of high silky abundance).

- In longline fisheries, where observer coverage is low (~5%), there is uncertainty about the true magnitude of silky shark catches and how consistently they are being released. WCPFC is promoting the expansion of electronic monitoring on longliners, which could verify that vessels are not secretly retaining silky sharks (e.g., cutting off fins for later sale). Compliance audits have occasionally found silky shark fins in vessel inspections, indicating some violations. The Commission has urged all members to ensure the no-retention rule is enforced through their domestic laws and to prosecute offenders.

- Scientists continue to recommend updated stock assessments for silky sharks in the Pacific. Improved data collection (such as genetic sampling of caught/released sharks to identify population structure, and tagging studies to track movements and survival) is needed. The WCPFC Shark Research Plan identifies silky sharks as a priority species for updated abundance indices and bycatch mitigation research, to gauge whether current measures are sufficient or if additional actions (like time-area closures around pupping grounds, or gear innovations) might be warranted.

Source documents: WCPFC Scientific Committee stock status (2013); CMM 2013-08 and FAD guidelines; SPC bycatch reports on silky sharks; IUCN Red List.

Whale Shark

Latest assessment | No quantitative stock assessment (data limited); global population trend monitored via sightings. |

Status | Endangered globally (IUCN 2016). Pacific subpopulations thought to be declining; slow breeder with high vulnerability to human impacts. |

Key findings | The whale shark is the world’s largest fish and is generally a rare bycatch in tuna fisheries – but when interactions do occur, they attract significant concern due to the species’ endangered status. Whale sharks roam across tropical oceans, including the WCPO, often migrating thousands of kilometers. They feed by filter-feeding on plankton and small fish near the surface, which unfortunately also brings them into the zone of purse-seine operations. Tuna, especially skipjack, sometimes aggregate around whale sharks (forming multi-species aggregations). Fishermen historically would capitalize on this by setting nets around the whale shark to catch the tuna school beneath, inadvertently capturing the shark as well. This practice, combined with the whale shark’s susceptibility to injuries or death in nets, posed a serious threat to local populations. Although whale sharks are not targeted by longliners (they very rarely bite baited hooks), they can suffer vessel strikes or entanglement in nets or ropes. Each individual whale shark is long-lived (70+ years) and matures late, so even infrequent mortalities can impact their population. Observational data in the Pacific (from dive tourism and research cruises) suggest fewer sightings in some areas compared to a few decades ago, though trends are hard to quantify. Major threats outside bycatch include directed take in some countries (now reduced due to protections) and ship strikes. |

Management | WCPFC introduced protections for whale sharks in purse-seine fisheries in 2012 (CMM 2012-04, later revised), recognizing the need to prevent their injury or death. It is now prohibited to deliberately set a purse seine net around a whale shark if one is observed in or near a tuna school. If a whale shark is inadvertently encircled (e.g., it was not seen before the set or wanders into the net), the crew must take actions to release it alive. Guidelines for safe release include: slowing the net retrieval, not submerging the whale shark under the net, and if possible, opening one end of the net or using a specifically designed large mesh panel through which the shark can escape. Crew are instructed never to gaff, harpoon, or use knives on a whale shark; instead, they may use a wide sling or canvas tarp under the shark if manual lifting is needed (for smaller individuals) or gently guide it out of the net for larger ones. Whale sharks are also listed as no-retention (though in practice, purse seiners have no reason to retain one). Observers must document any whale shark interaction in detail. Through these measures, WCPFC aims to ensure that encountering a whale shark does not result in its harm. Many member countries have also independently protected whale sharks in their waters (e.g., full species protection, ecotourism promotion instead of fishing). The combination of international and national measures provides a safety net for this iconic species, although ensuring effective implementation at sea remains critical. |

Ecology and fishery interaction

- Whale sharks inhabit open oceans as well as coastal regions, following blooms of plankton and small fish. In the WCPO, they are often sighted in the tropics (10°N–10°S) but can range into subtropical waters seasonally. They have predictable aggregation sites in some areas (for example, parts of Micronesia or the Coral Triangle) where they come to feed. Tuna purse-seine fisheries overlap with whale shark habitat particularly in equatorial surface fisheries. When a whale shark is present under a school of tuna, the tuna tend to stay with the shark, which historically made it an attractive “natural FAD” from a fishing perspective. Unfortunately, when a purse seine is set around the school, the whale shark can become trapped. Given their massive size (up to 12+ meters), handling them is extremely challenging and dangerous if not done carefully. In a few documented cases, whale sharks tangled in nets have died from stress, injury, or inability to move water across their gills.

- It’s worth noting that whale sharks spend a lot of time near the surface (often basking or feeding), which is why they frequently cross paths with surface fishing gear and vessels. They can dive to great depths but generally come back to surface waters where food is abundant. They do not evade nets or boats quickly, which makes them easy to capture inadvertently. Whale sharks are plankton-eaters and do not bite bait, so interactions with longlines are almost nil – the main risk in longlining might be if a whale shark gets entangled in a line or if a longline vessel strikes one at the surface, but these are very rare events.

Safe release practices

- When a whale shark is spotted inside a purse seine, best practice is to stop the net from closing further and avoid bringing the shark alongside the power block. WCPFC guidelines suggest slowing down the winch and keeping the whale shark in an area of the net with sufficient water (so it can continue swimming). Many fleets use a “lowering the corks” method: one section of the corkline (top of the net) is dropped to create an escape opening large enough for the whale shark to swim out on its own. This method has proven effective, particularly for energetic sharks that can navigate out when given the chance.

- If the shark is exhausted or entangled, crews may employ a more hands-on approach. For smaller whale sharks (juveniles), a few strong crew members might enter the water or lean over the skiff to carefully cut any net wraps and guide the shark out or even lift it with a stretcher if feasible. For large individuals, cutting the net may be a last resort to free the animal – some companies accept the cost of net damage as a trade-off for saving an endangered animal. In all cases, minimizing the handling time is critical: whale sharks can suffer internal injuries or become fatally stressed if restrained too long. Crews are trained to never tie ropes around the shark or pull it by the gill slits or tail (practices that have caused fatalities in the past). Instead, the emphasis is on gentle guiding and patience.

- After a release, observers note the condition of the whale shark (e.g., “swam away strongly” vs “weak or injured upon release”). This information helps assess how effective current release techniques are. Some collaborative programs also tag whale sharks that have been encircled and released, tracking their movements and survivorship post-interaction. These studies suggest that whale sharks can survive a net incident if released properly, though injuries like abrasion or temporary behavioral changes have been observed.

Monitoring and cooperation

- The reporting of whale shark interactions to WCPFC is mandatory. Annual reports by members include details such as the number of sets where whale sharks were present, how many were released alive, and any mortalities. This data shows that the incidence of whale shark capture is relatively low (a small percentage of FAD sets involve a whale shark), and since the prohibition on intentional sets was enacted, reported mortality has decreased. Nonetheless, even a handful of deaths is concerning for such a slow-growing species, so WCPFC continues to refine measures.

- Cooperation with the IATTC (Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission) in the Eastern Pacific has been important, since whale sharks traverse the whole Pacific. Both RFMOs now have similar rules against setting on whale sharks, ensuring that vessels on either side of the 150°W boundary operate under consistent conservation measures. Additionally, WCPFC members support global efforts like the International Whale Shark Photo-ID database and CITES Appendix II listing (which regulates international trade in whale shark products) to safeguard the species beyond just fisheries rules.

- On a national level, many Pacific countries have turned whale sharks into valuable assets for tourism rather than as bycatch. For instance, places like Palau and Fiji have shark sanctuaries that ban all shark catches, including whale sharks, in their waters. These broader protections complement WCPFC’s measures on the high seas, creating safer migratory corridors. Continued education of fishing crews about the ecological and economic importance of live whale sharks (as tourism draws) further incentivizes careful release.

Source documents: WCPFC Whale Shark CMM 2012-04; observer guidelines for whale shark release; IUCN assessment (2016); regional reports on whale shark encounters.

Blue Shark

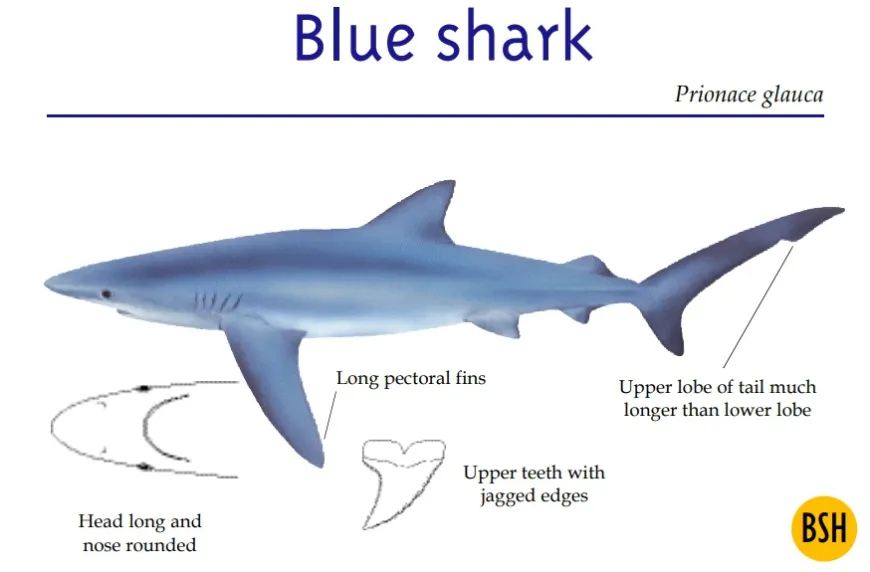

Latest assessment | 2018 North Pacific assessment (ISC) – stock not overfished; no formal South Pacific assessment (indicators monitored). |

Status | Near Threatened globally (IUCN 2018). Most abundant oceanic shark, but heavy fishing pressure in places; populations stable in some regions, declining in others. |

Key findings | Blue sharks are wide-ranging predators found throughout temperate and tropical oceans. In the Pacific, they form the bulk of shark bycatch in many pelagic longline fisheries – especially in the North Pacific and subtropical zones. Their biology (faster growth, earlier maturity, larger litters up to 50+ pups) makes them more productive than most other shark species, which has so far prevented extreme depletion on a global scale. In the North Pacific, stock assessments have indicated that blue sharks have been fished at moderately high levels but appear to be at or above the biomass needed for maximum sustainable yield (i.e., not currently overfished). However, this comes with uncertainties, and any significant increase in catch could tip the balance. In the South Pacific, data are sparser, and there are concerns about possible unrecognized declines. Blue sharks were historically targeted by some fleets for their high-quality fins and as secondary catch for meat, but today much of the catch is still incidental while targeting tuna and swordfish. Bycatch levels are very high – millions of blue sharks are caught annually across the Pacific. While a higher fraction survive capture compared to less hardy species, post-release mortality (especially from longline capture stress) can be substantial. The species’ Near Threatened status reflects that although not in crisis like some sharks, careful management is needed to avoid overexploitation given the sheer volume of removals. |

Management | WCPFC has not implemented a strict no-retention policy for blue sharks, recognizing that some level of utilization is sustainable if properly managed. Instead, the approach has been to improve monitoring and encourage science-based limits. Members are required to report blue shark catches (landings and releases) in their annual data submissions. The general shark measures – such as the fins-attached policy – mean any blue sharks retained must be landed whole with fins on, curbing wasteful finning. WCPFC’s ban on wire leaders also indirectly benefits blue sharks by increasing their chance to escape capture. In the North Pacific, where most blue shark catch occurs, WCPFC relies on the scientific advice of the ISC: after the positive 2018 assessment, no catch quotas were imposed, but there is an understanding that fishing mortality should not increase. Some member states have instituted national management for blue sharks (e.g., setting annual catch limits for their fleets or requiring live release of a portion of the catch). WCPFC has also considered but not yet adopted a Pacific-wide blue shark measure; instead the Commission tasked its Scientific Committee to regularly review blue shark status. If future assessments indicate decline or higher uncertainty, the Commission may move to set explicit limits or retention bans. For now, blue sharks can be legally retained in WCPFC fisheries, but full utilization rules apply, and members must ensure their fleets do not engage in directed shark fishing without Commission-approved management plans. |

Distribution and catch

- Blue sharks have a cosmopolitan distribution, mostly in open ocean waters between roughly 50°N and 50°S. They prefer cooler temperate waters compared to many tropical sharks, which is why they are especially common in the North Pacific transition zone and in subtropical regions. In the WCPO, significant blue shark bycatch comes from longline fleets operating in the North Pacific (Japan, Taiwan, USA, etc.) targeting swordfish and tuna. They are often caught in cooler-water fisheries targeting albacore tuna as well. Blue sharks undertake long migrations and have been tracked crossing entire ocean basins. This means the WCPO stock likely mixes with the Eastern Pacific, making international cooperation important.

- In longline fisheries, blue sharks are often caught on deeper sets (they are known to dive deep during the day and come closer to the surface at night). They readily take a variety of baits. Because they are more robust (physically) than species like hammerheads or threshers, a fair number of blue sharks survive the hauling process, especially if the soak time is not too long. Some are brought onboard alive and then either released or landed for sale. In contrast to purse seine fisheries – which very rarely catch blue sharks since these sharks don’t typically aggregate under FADs – the vast majority of blue shark mortality in the WCPO comes from longlines. There is also likely unreported mortality from illegal fishing or artisanal gillnet fisheries in some regions.

- Due to their prevalence, blue sharks have historically been an important part of shark fin trade (their fins are of medium-high value) and also used for meat (often sold as cheaper shark meat or processed into products like fish balls). However, increased regulations and declining fin prices have reduced targeted effort on blue sharks. Now they are mostly utilized when caught incidentally. Still, given the large catches (tens of thousands per year in WCPO reported, possibly more unreported), even moderate mortality rates need monitoring to ensure the population remains healthy.

Best practices and fleet actions

- Some WCPFC members have adopted voluntary measures in their longline fleets to minimize unnecessary blue shark mortality. For example, certain fleets encourage the release of live blue sharks, especially juveniles or pregnant females, since the species has relatively good survival chances if released promptly. Where market demand for blue shark is low, skippers may prefer to cut sharks off the line to save space and time (which incidentally benefits the shark if it swims away). Making use of circle hooks (which tend to hook fish in the mouth) can also reduce internal injuries in sharks, meaning those that are released have a better chance of survival.

- Japan, the U.S., and other nations have developed shark management plans that include blue sharks. These often feature measures like trip limits (e.g., capping how many can be landed per trip to deter targeting) or bycatch ratio limits (sharks can only make up a certain percentage of the catch). Such measures keep blue shark retention at moderate levels. Additionally, if observers notice a particularly high shark bycatch in a set or area, some vessels will move to a different area to avoid continuous shark catches (this is more common when shark catches are interfering with fishing operations by tangling gear or biting off target fish).

- Research into gear modifications is ongoing. Trials of electropositive metals or magnets on hooks (which theoretically repel sharks) have had mixed results but could one day help reduce blue shark catch without affecting tuna. Also, time-of-day adjustments – for example, setting longlines only at night at depths where tuna are present but blue sharks might be less active – are being explored. However, given blue sharks’ wide vertical and horizontal range, completely avoiding them while tuna fishing is challenging. A combination of moderate retention with full utilization and selective release seems to be the practical strategy at present.

Data and stock assessment

- The North Pacific blue shark stock assessment is updated periodically by the ISC. The 2018 assessment was cautiously optimistic, but it highlighted data gaps such as uncertainties in historical catch (particularly before the year 2000) and the need for better reporting of discards. Efforts are underway to improve species-specific logbook reporting and to integrate observer data into catch estimates. The South Pacific stock is less studied; WCPFC’s Scientific Committee has encouraged collection of more data from southern hemisphere fleets and potentially a separate assessment or analysis for that region if enough data become available.

- WCPFC is also working on shark indicators (simple metrics like catch per effort or average size) as interim measures of stock health between assessments. For blue sharks, tracking trends in these indicators can alert managers to any sudden changes. For instance, if observers start seeing fewer blue sharks per 1000 hooks than before, or a shift to mostly smaller individuals, that could signal overfishing, prompting a management response even before a full assessment is done.

- International management of blue sharks may eventually include explicit quotas or limits if warranted. The challenge is balancing the fact that blue sharks are currently relatively plentiful (so imposing strict limits might be seen as unnecessary by some fishing nations) versus the precautionary approach given their importance in the ecosystem and value in fisheries. WCPFC’s current stance is to closely monitor and encourage responsible fishing rather than hard limits, but this could evolve with new scientific evidence.

Source documents: ISC (2018) North Pacific Blue Shark assessment; WCPFC Shark CMM 2010-07 and 2014-05 (fins attached policy); national shark management plans; IUCN Red List.

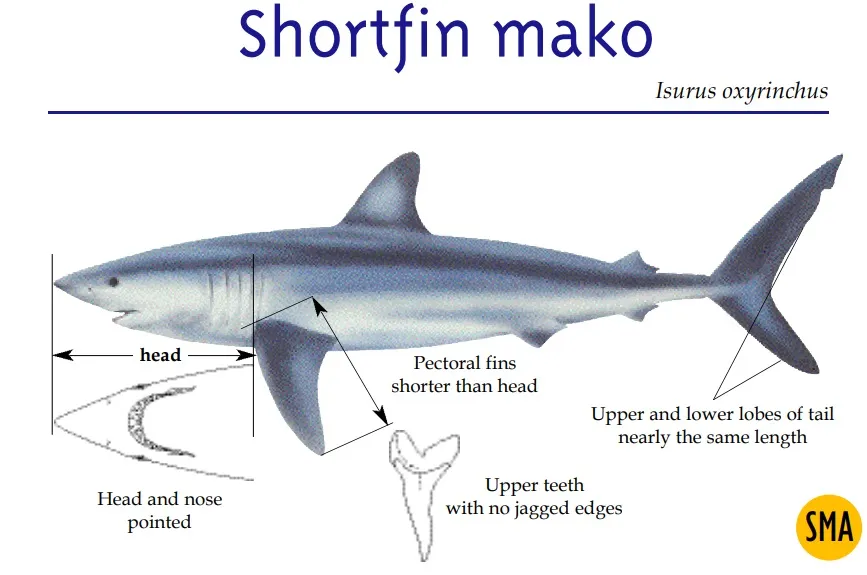

Shortfin Mako Shark

Latest assessment | 2015 North Pacific assessment (ISC) suggested no overfishing; 2019 risk analysis for South Pacific (data-poor). |

Status | Endangered globally (IUCN 2019). Pacific stocks uncertain: likely lower abundance in some areas, but not fully assessed; slow-recovering species. |

Key findings | The shortfin mako is a highly valued pelagic shark known for its speed and athleticism (famously, it’s the fastest shark). In the WCPO, makos are caught primarily by longline fisheries as bycatch, although there has been some targeting due to their high-quality meat and fins. They are less common in tropical purse seine catches (as they prefer cooler, temperate waters and do not aggregate under FADs). Makos have relatively low reproductive productivity – females mature late (around 7–8 years or older) and have small litters (typically 4–25 pups, and not every year). This life history makes them vulnerable to overfishing. In the Atlantic, steep declines have been documented, leading to strict measures there. In the Pacific, trends are not as clear: the North Pacific assessment last decade indicated the population might have been stable or only mildly declining under then-current catches, but data deficiencies made the conclusion uncertain. The South Pacific population is even less understood. Nonetheless, signs such as reduced sightings by some fishers and fewer large, mature makos in catches have raised concerns. Additionally, shortfin makos are sought after in recreational fisheries (for sport) and can be impacted by those catches too. Their endangered status globally reflects both recorded declines and the potential for rapid decline if fishing pressure increases. |

Management | WCPFC has not yet instituted a commission-wide ban on retaining mako sharks, but it has highlighted makos as a species of concern. Countries are encouraged to release live makos, especially juveniles and pregnant females, and to avoid any targeted fishing on this species. The general WCPFC shark measures (fins-attached, no shark lines, etc.) apply, which means finning of makos is prohibited and some gear changes help reduce mako catch. For example, because makos often bite at bait near the surface, the ban on shark lines (which target surface sharks) likely cut down a portion of mako catches. Some member nations have implemented domestic rules for makos: these include size limits (to protect juveniles), trip limits, or even no-retention in certain exclusive economic zones. WCPFC’s Scientific Committee has recommended improving data collection for makos and keeping a close watch on indicators. The Commission agreed that if evidence shows North or South Pacific mako stocks declining or being overfished, it would consider additional measures – such as catch limits or a move to no-retention – in line with advice. Additionally, since 2019 the shortfin mako has been listed on CITES Appendix II, meaning international trade (e.g., exporting fins or meat) requires permits and a finding that the catch was sustainable. This external regulation indirectly compels WCPFC members to ensure their mako catches are sustainable and documented, or else forgo retention. Overall, current management relies on a mix of national actions and general shark protections, with the acknowledgment that stronger WCPFC-level intervention may be needed if mako mortality isn’t kept in check. |

Distribution and catch profile

- Shortfin makos are found throughout the Pacific but are most common in temperate and subtropical waters. In the WCPO, higher catch rates occur in the subtropics (~20–40° latitude) rather than in equatorial waters. Longline fisheries targeting species like albacore, bigeye tuna, or swordfish incidentally catch makos, particularly when using steel leaders (now banned) or when fishing shallower sets where makos hunt. Makos are powerful and often still alive when brought to the vessel; they can even damage gear or injure crew if not handled carefully. Because of their value, many were historically kept rather than released. In some regions (for instance, off New Zealand or Japan), makos are also caught by recreational anglers, though those catches are outside WCPFC’s purview, they do contribute to overall mortality.

- Makos are known to undertake long-distance movements but also show seasonal site fidelity (coming to certain regions when prey like squid or small tuna are abundant). They tend to be solitary hunters. When hooked on a longline, makos often put up a fierce fight, which can lead to fatigue; however, they also have a relatively high chance of surviving capture if handled properly because they must keep water flowing over their gills (ram ventilation) to breathe, and the act of being pulled by the line can suffice if not too long. That said, if a mako is hooked and struggles for many hours, it can die on the line from exhaustion. Observer data indicates a mix of outcomes: some makos are dead on retrieval, others come aboard thrashing.

Bycatch mitigation and handling

- With wire leaders no longer allowed, many makos that would have been firmly hooked can now sometimes escape by biting off monofilament leaders. While fishermen losing a potentially valuable catch may not favor that, it is a conscious compromise to aid shark conservation. Crews are encouraged to release makos that do come up alive: one common practice is to cut the branch line as soon as the shark is at the surface, to avoid having to bring it on deck at all. This eliminates the danger to crew and increases the shark’s survival odds (since less time out of water and less stress). If a mako is brought on deck (intentionally or accidentally), extreme caution is needed – crew often cover the shark’s eyes with a cloth and secure the tail with a rope to control it while the hook is removed. Some fleets have barbless hooks or use bolt-cutters to simply cut the hook shank and let the shark go, rather than trying to pry the hook out.

- Avoidance measures are not well-developed for makos specifically, but some ideas include temporal closures if areas of high mako catch are identified. For example, if data show a certain quadrant of the ocean has seasonally high mako interactions, the Commission could advise fleets to limit effort there during those times (this is not yet in place, but it’s an option). Another possible mitigation is incentivizing the use of “hook timers” or similar devices that can indicate a big catch early – if a mako is hooked, some smart gear might alert fishermen who could then choose to retrieve the line sooner to release the shark before it dies. These technologies are still experimental.

- The role of education is also important: WCPFC and NGOs have provided materials to fishing crews illustrating how to identify mako sharks (to differentiate shortfin vs longfin mako, though longfin is very rare in WCPO, nearly all are shortfin) and the importance of their conservation status. By fostering a conservation ethic (similar to how many crews have learned to care about releasing sea turtles or seabirds), the hope is that fishers will see live release of makos not just as a rule but as the right thing to do when feasible.

Research and future management

- Data collection on mako sharks in the WCPO is being improved through initiatives like biological sampling (e.g., collecting vertebrae for age and growth studies, reproductive organs from any dead specimens to understand maturity). The Shark Research Plan under WCPFC specifically lists mako age/growth and catch history improvements as priorities. One outcome expected in coming years is a new Pacific-wide assessment or at least a productivity-susceptibility analysis to gauge how current fishing levels might impact makos in the long term.

- International cooperation is crucial since makos move across management boundaries. WCPFC liaises with the IATTC and ICCAT (Atlantic) to share knowledge on effective measures. For example, ICCAT recently adopted a no-retention measure for North Atlantic makos due to severe depletion there; while the Pacific situation is less dire, WCPFC is watching that case closely. If the Pacific stock shows signs of decline, WCPFC may follow suit with stricter measures. The CITES listing of makos in 2019 has already prompted better record-keeping; countries must demonstrate exports are sustainable. This effectively pushes WCPFC members to limit mako catch to sustainable levels or risk losing export markets.

- The next few years will likely see WCPFC discussing the idea of explicit mako catch limits or a move to mandatory live release. The balance will hinge on scientific evidence and the willingness of fishing nations to forego some short-term catch for long-term conservation. Given the mako’s value, any proposal for full no-retention could be contentious – some members may prefer setting a quota or minimum size (to protect juveniles) as an alternative. The Scientific Committee’s advice will be central: if they advise, for instance, that a X% reduction in mortality is needed to keep the stock healthy, the Commission can then debate the best way to achieve that (be it a ban on retention or gear/effort controls).

Source documents: ISC analyses of North Pacific mako (2015); WCPFC Shark Research Plan 2019–24; CMM 2014-05 (shark measures); CITES Appendix II implementation reports; IUCN Red List.

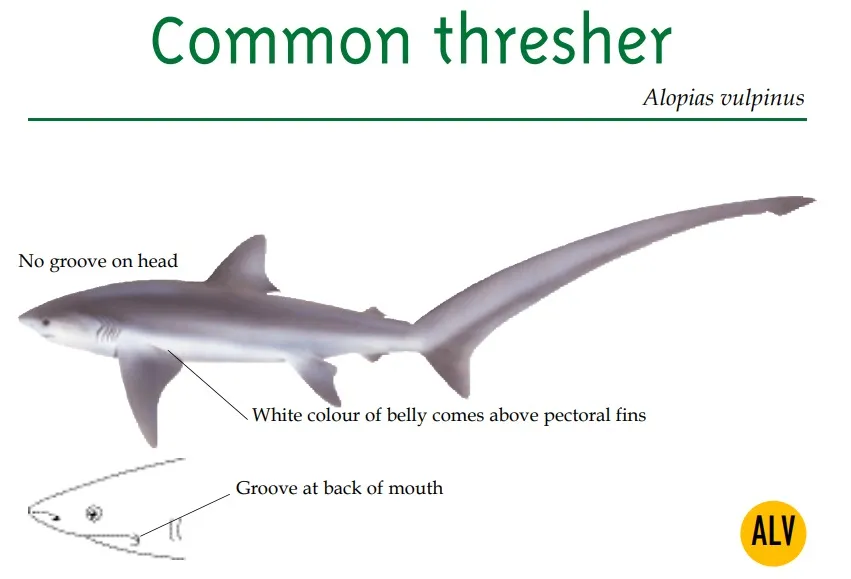

Thresher Sharks

Latest assessment | No WCPFC stock assessment (data-limited); IUCN assessments (2019) for species in this family. |

Status | Vulnerable to Endangered globally (varies by species). Bigeye Thresher (Alopias superciliosus) considered Vulnerable globally; other threshers similar or worse. All have low productivity and are in decline. |

Key findings | Thresher sharks (family Alopiidae, including the bigeye, common, and pelagic thresher) are distinctive for their very long tail fins, which they use to stun prey. In the WCPO, the bigeye thresher is the most frequently caught thresher species in pelagic fisheries, as it inhabits oceanic waters and dives deep during the day. Threshers are highly vulnerable to overfishing: they mature late (often over 8–9 years old), have small litters (usually 2–4 pups), and many individuals die upon capture due to stress (they are sensitive to being hooked). Although not typically targeted in WCPFC fisheries, they end up as bycatch in tuna longlines. Data from observer programs indicate that bigeye threshers have experienced significant declines in catch rates in some Pacific regions since the 1990s, consistent with global trends. These declines are hard to quantify precisely due to sparse data, but the IUCN status listings (pelagic thresher and common thresher are Endangered globally, bigeye thresher Vulnerable) reflect substantial population reductions. One alarming aspect is that a large proportion of thresher sharks caught on longlines are found dead when the gear is hauled – their physiology (being ram ventilators like makos) and stress response cause high at-vessel mortality. This means even prompt release often comes too late to save them. Historically, thresher shark fins entered the trade (though of moderate value), and carcasses were sometimes retained for meat, but as awareness of their status grows, many fisheries now prohibit retention. Thresher sharks also occasionally entangle in purse seine nets or FADs, although this is relatively uncommon. |

Management | Within WCPFC, there isn’t a standalone conservation measure specific to thresher sharks yet; however, several provisions indirectly afford them protection. The ban on shark lines and wire leaders reduces targeted capture of threshers to some extent, as these sharks often struck at shallow baits near floats (when such lines were used). Moreover, many WCPFC members have chosen to implement domestic no-retention rules for threshers: for instance, some fleets operating in the high seas will not keep thresher sharks even though not explicitly required by WCPFC, due to national laws or policies stemming from the sharks’ threatened status. The Commission’s reporting requirements mean all thresher catches (alive or dead) must be noted by observers or in logbooks, helping to track their occurrence. Regionally, thresher sharks have been highlighted in workshops as candidates for stronger management – both ICCAT and IATTC (Atlantic and Eastern Pacific) have prohibited retention of thresher sharks (with some exceptions). WCPFC has discussed aligning with these measures. Pending a formal WCPFC ban, the expectation is that any thresher shark caught should be released if alive. In practice, since most come up dead, the focus is on reducing capture in the first place. Some ongoing scientific studies under the Shark Research Plan aim to improve data on thresher biology and catches, which could inform future WCPFC action (like setting safe retention limits or forbidding retention entirely). Meanwhile, the thresher’s inclusion in CITES Appendix II (for bigeye and common thresher) means international trade in their parts is now regulated, acting as an external check on any large-scale utilization. |

Behavior and bycatch characteristics

- Bigeye threshers, true to their name, have large eyes adapted for low-light conditions, allowing them to hunt in deep water. They typically spend daylight hours at depths of 300–500 m and come closer to the surface at night to feed on squid and small fish. Longline sets that soak overnight can intercept them during these vertical movements. Once hooked, threshers are not as vigorous as makos, but their chances of survival are slim. Studies have shown extremely high physiological stress in threshers upon capture (they often exhibit something akin to fatal shock). This is one reason that simply mandating release, while important, may not substantially reduce mortality – avoidance of capture is more critical.

- The other thresher species (common and pelagic) are more coastal or epipelagic, so they are less encountered in high-seas tuna fisheries, though some bycatch does happen near continental shelves or island chains. Common threshers tend to stay closer to coasts and are more often caught in coastal gillnets or by recreational fisheries than by longliners in the open ocean. Pelagic threshers overlap with bigeye threshers in some tropical offshore areas but are generally smaller and may not bite the larger hooks used in tuna longlining as frequently. Nonetheless, any thresher sighted in the catch is treated with the same concern due to their poor survival prospects.

Mitigation options

- Reducing thresher shark bycatch is challenging. One practical step is temporal/spatial avoidance: identify hotspots where bigeye threshers are commonly caught (for example, certain seamount areas or convergence zones) and advise vessels to avoid those if possible. If a vessel notices multiple threshers in consecutive sets, they might shift location to prevent additional mortalities. However, because thresher encounters are relatively rare events scattered across a huge ocean, a broad-based measure like an area closure is hard to justify unless a very clear hotspot is identified.

- Gear modifications might help to a degree. Using slightly deeper hook deployments could miss some threshers that stay above certain depths. Additionally, circle hooks might reduce the likelihood of a thresher being deeply hooked – possibly leading to more bite-offs (the shark escaping) or at least a mouth hooking that could be removed. Some research suggests that bigeye threshers are caught predominantly on the shallowest hooks of deep sets; thus, removing the shallowest few hooks (a measure analogous to turtle mitigation) could reduce thresher catch. WCPFC has not mandated this, but individual fleets aware of high thresher bycatch have experimented with avoiding placing hooks near floats.

- On the handling side, for the minority of threshers that are found alive, gentle release is still encouraged. Crew should not gaff or lift the thresher by the tail (despite the tail being long, it’s fragile and full of muscles the shark needs). The proper method is to cut the line near the hook or use a de-hooker if the hook is accessible and the shark is docile. Because threshers have smaller teeth and are not aggressive to boats, sometimes crew can safely reach the hook with a pole. But again, since most are dead, the emphasis must be on avoiding getting them on the line in the first place.

Data and monitoring needs

- A significant gap is the lack of comprehensive data on thresher catch and mortality. Many longline fisheries historically did not report shark species at fine resolution, so catch records often lump threshers into an “other sharks” category. Observer programs have improved this, but coverage is low. To address this, WCPFC’s Shark Research Plan includes projects to reconstruct thresher catch histories using available data and extrapolation. By estimating how many threshers were likely caught in the past decades, scientists can gauge the extent of decline and current exploitation rates.

- There is interest in conducting a Pacific-wide assessment for bigeye thresher (the most relevant species for high seas). Such an assessment would require pooling data from multiple RFMOs and national sources. WCPFC scientists are collaborating with IATTC and ICCAT scientists since these sharks span oceans. Even if a full assessment is not feasible, a qualitative risk assessment has rated bigeye thresher as one of the most vulnerable shark species in tuna fisheries, reinforcing the call for precautionary management.

- In terms of management next steps, the WCPFC could consider a proposal similar to other RFMOs – an explicit ban on retaining any thresher sharks (Alopiidae) caught in its Convention Area. This would harmonize the Pacific with the Atlantic and Indian Ocean measures and send a clear signal to fishers. The downside (as noted) is that nearly all thresher bycatch are dead discards, so a no-retention rule mainly serves to prevent any incentive to target them or sell them. It’s a necessary piece, but not sufficient to reduce mortality. Therefore, it would likely be coupled with continued gear and effort measures, plus international cooperation on protecting critical habitats (like nearshore nursery grounds for threshers, often within national EEZs).

Source documents: IUCN Red List assessments for bigeye, pelagic, and common threshers (2019); WCPFC bycatch data summaries; IATTC/ICCAT shark resolutions; SPC Shark Research Plan reports.

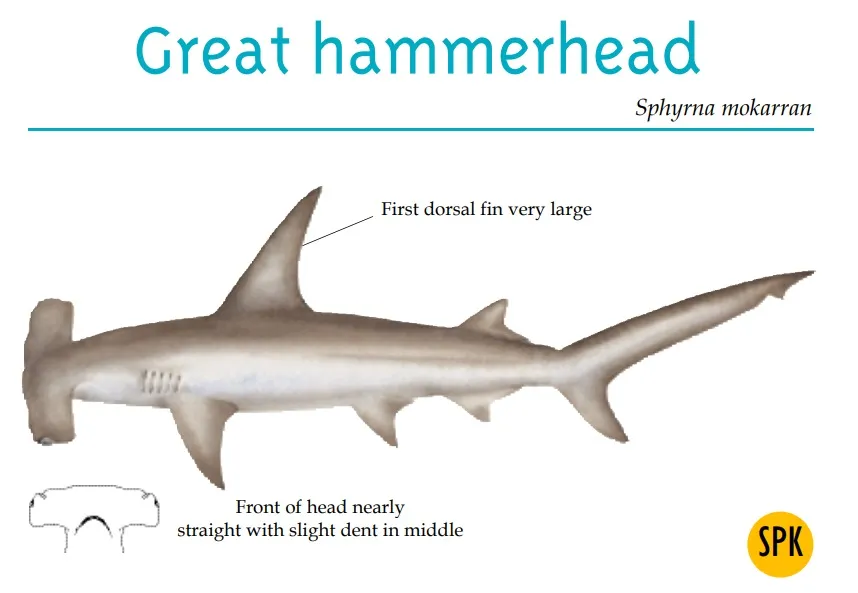

Hammerhead Sharks

Latest assessment | No WCPO stock assessment (very limited data); global status reviews (2020) for scalloped and great hammerheads. |

Status | Critically Endangered (Scalloped & Great Hammerhead, IUCN 2019–2020). Extremely low numbers regionally. Smooth hammerhead is Vulnerable. Overall, severe declines globally (est. 80%+ in many areas). |

Key findings | Hammerhead sharks (family Sphyrnidae) are among the most threatened shark families due to a combination of high susceptibility to capture and high value (their fins are among the most prized in the shark fin trade). In the Pacific, the primary species of concern are the scalloped hammerhead (Sphyrna lewini) and to a lesser extent the great hammerhead (S. mokarran) – both largely coastal species that occasionally range into pelagic waters. Scalloped hammerheads have particular life-history traits (they form large schools, especially of juveniles, and use inshore nurseries) that made them easy targets in coastal fisheries. While most hammerhead mortality occurs in coastal gillnet and longline fisheries (often outside WCPFC high-seas fisheries), they do appear as bycatch in tuna fisheries as well. Juvenile scalloped hammerheads have been recorded by observers in purse seine FAD sets and occasionally in longline catches, albeit at low frequency. Great hammerheads, being more solitary, are infrequently hooked in pelagic longlines. Nevertheless, given their critical status – these species have undergone estimated declines of 80–95% from baseline in many regions – any additional mortality in WCPFC fisheries is taken seriously. Hammerheads are known to be extremely stress-sensitive; great hammerheads in particular often die even from relatively short capture events (a phenomenon noted in scientific tagging studies). Their populations recover very slowly, if at all, without near-zero mortality. Because of this, international bodies (like CITES and CMS) have listed hammerheads for strict protection, and WCPFC has recognized that hammerheads warrant highest precaution. |

Management | WCPFC’s shark measures implicitly cover hammerheads: the finning ban and reporting requirements apply to them, and there is a strong encouragement to release any hammerhead caught alive. In practice, many WCPFC members have implemented domestic bans on retention of hammerhead sharks in their fleets, effectively extending protection in the high seas. For example, the US and several FFA member countries prohibit their vessels from retaining hammerheads, aligning with hammerheads’ protected status under domestic laws. While a specific WCPFC CMM (Conservation and Management Measure) for hammerheads has been proposed in the past (to make no-retention explicit at the Commission level), it has not been formally adopted due to varying national positions. Despite the lack of a standalone measure, there is de facto non-retention in many cases. Additionally, any international trade of hammerhead parts is tightly controlled by CITES (scalloped, great, and smooth hammerheads are all listed in Appendix II since 2013), meaning that even if a hammerhead were retained, exporting its fins or products would require permits and sustainability findings – a strong disincentive. Observers are instructed to document hammerhead catches meticulously, given their rarity; length, condition (alive/dead), and photos or samples (where possible) are collected for research. WCPFC’s Scientific Committee continues to recommend avoiding hammerhead catches altogether. The Commission supports collaboration with coastal states to protect known hammerhead nursery areas (often in archipelagic waters) so that fewer juveniles recruit to offshore fishing areas. In summary, while not encapsulated in one WCPFC resolution, hammerheads are functionally treated as protected species across much of the WCPO tuna fisheries, with emphasis on zero retention and safe release. |

Habitat and bycatch patterns

- Scalloped hammerheads primarily inhabit continental shelves, island terraces, and coastal zones, but juveniles and subadults can venture into the open ocean, especially in areas with mesoscale eddies or convergence zones that concentrate food. These young hammerheads sometimes end up around FADs or debris lines, which explains why purse seiners have occasionally caught them. Observer records show that such events are rare but not absent – usually single-digit counts of small hammerheads in FAD sets in a given year across the WCPO. Longline interactions are also infrequent; when they occur, it’s often on fleets operating near the edges of EEZs or seamounts where hammerheads roam in deeper water. Great hammerheads, being larger and more solitary, are even less encountered offshore; a few have been recorded by observers on longlines, generally in subtropical areas. Smooth hammerheads prefer temperate waters and are occasionally caught by temperate longliners, but they too are not a common catch compared to blues or makos.

- Hammerheads that do end up on a line or in a net have very low survival odds. Scalloped hammerheads, if tangled in a net or kept on a line for any length of time, often suffocate due to their high oxygen demand and sensitivity. Even if alive at release, post-release mortality is suspected to be high; satellite tagging studies in other regions found many tagged hammerheads died shortly after release from longlines, likely from capture stress. This makes prevention of capture the critical goal. Also, because hammerhead fins are still valuable on black markets, there is a risk that if one is caught and already dead, crew might be tempted to retain the fins. Strict enforcement (through port inspections and observer oversight) is essential to ensure even dead hammerheads are not kept. Instead, they should be discarded (with documentation) to remove any profit motive.

Risk reduction and best practices

- For purse seine fisheries, one protective measure is the move to non-entangling FADs, as previously mentioned. Old-style FADs with loose netting were known to entangle various marine life, including small hammerheads that might investigate the FAD. Eliminating that risk helps. Purse seine skippers are also made aware that if a hammerhead is seen in the net, it should be a priority to release; because hammerheads can be dangerous (they can bite if handled incautiously) but also fragile, the recommended method is to gently guide them out of the net opening or use a dip net for very small ones. Direct lifting by the cephalofoil (the “hammer” head) or by the tail is discouraged as it can injure the shark.

- Longline fleets can reduce incidental hammerhead catch by avoiding known coastal hotspots, especially nursery areas. For instance, scalloped hammerheads have nursery areas in parts of Indonesia, the Philippines, and some Pacific Islands – ensuring longline effort is minimal in adjacent offshore waters during pupping season can help. Some RFMOs have suggested gear modifications like circle hooks could improve survival if a hammerhead is hooked (by reducing bleeding), but given hammerheads’ low survival regardless, gear changes have a limited effect. The best practice remains: if a hammerhead is on the line and alive, release it immediately by cutting the line (ideally leaving minimal trailing line). If it’s found moribund or dead, crew should still not retain any part – showing that even a dead specimen has zero value to them enforces the conservation ethic.

- Another important aspect is training and identification: hammerhead sharks are easy to recognize due to their head shape, and crew/observers must distinguish them from other shark species. Misidentification isn’t common for hammerheads, but it’s critical that any catch of these species is logged properly given their rarity. Some programs have encouraged fishers to collect a small tissue sample from any dead hammerhead (if safe to do so) for genetic analysis; this can help scientists determine which population (e.g., which breeding stock) the shark came from. Such information might reveal, for example, that hammerheads caught in the high seas originated from a particular coastal nursery, highlighting where conservation efforts should focus.

Conservation outlook

- Hammerhead conservation largely depends on what happens in coastal waters (juvenile nurseries) where most are caught. Nevertheless, WCPFC’s role in eliminating additional high-seas mortality is important. A proposal for a hammerhead-specific measure could re-emerge, aiming to formally prohibit retention Commission-wide. Given the critically endangered status, this would likely be supported by the scientific community. Harmonizing WCPFC’s approach with other RFMOs (which already ban hammerhead retention in many cases) ensures that no ocean region is a loophole for hammerhead exploitation.

- The Commission also collaborates with organizations like the Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP) and national wildlife authorities to raise awareness about hammerhead status. Capacity-building workshops for fisheries observers often include modules on handling and recording interactions with endangered species, including hammerheads. Observers in some Pacific Island fleets have begun tagging any hammerheads they release (if alive) with archival tags to gather more data on their fate and movements. Although sample sizes are small, each data point is valuable for such a rare encounter species.

- Ultimately, the hope is that through a combination of zero retention, improved bycatch mitigation, and strong coastal protections, hammerhead shark populations might eventually stabilize or recover. However, given their biology, any recovery will be a slow, multi-decade process. The immediate aim is to halt further declines. WCPFC’s strengthening stance on shark bycatch indicates that hammerheads will remain a high priority in the coming years, with management measures likely to become more stringent if current efforts are deemed insufficient.

Source documents: IUCN Red List (2019/2020) for Scalloped and Great Hammerheads; WCPFC bycatch reports & proposals (2014–2021); CITES listings and annotations; national conservation plans for hammerheads.

How WCPFC manages shark bycatch

- Ban on shark finning: WCPFC prohibits the removal of shark fins at sea and discarding of carcasses. Since 2014, a “fins naturally attached” policy has been in place to enforce this, meaning vessels must land sharks with fins still attached. This ensures full utilization and makes it easier to monitor and identify shark catches by species, thereby eliminating the wasteful practice of finning.

- No-retention policies: The Commission has designated certain vulnerable shark species for mandatory release. Oceanic whitetip sharks and silky sharks have been no-retention species for over a decade – any caught must be released (and if possible, alive). Similarly, whale sharks cannot be retained (and in fact purse seiners cannot even set on them). In practice many fleets also do not retain hammerheads or threshers, due to either national laws or conservation ethics, effectively extending protection to those species as well. These no-retention rules remove economic incentives to target or keep these sharks.

- Longline gear regulations: To reduce shark catches, WCPFC banned the use of wire trace leaders and shark lines in longline fisheries (CMM 2014-05). Wire leaders made it nearly impossible for sharks to escape once hooked, whereas monofilament leaders can be severed by the shark’s teeth. Removing shark lines (which were extra hooks near the surface specifically aimed at sharks) has cut down shallow shark bycatch significantly. Additionally, vessels are required to carry and use specialized equipment (line cutters, de-hookers) to safely release sharks, especially those species under no-retention.

- Purse seine measures: Purse seine vessels must avoid intentionally deploying nets on schools associated with whale sharks (to protect that species). There are also guidelines to safely release any sharks (primarily silky sharks) found alive in the net or entangled on FADs. The shift to non-entangling FAD designs is a key preventive measure – by eliminating open net webbing on FADs, entanglement of sharks (and other fauna like turtles) is greatly reduced. Crew training programs have been implemented so that purse seine operators know how to spot and free sharks during net operations with minimal harm.

- Data reporting and scientific monitoring: Members of WCPFC are obligated to report shark catches by species wherever possible, including numbers released and discarded. The Regional Observer Programme provides vital independent data on shark bycatch, and there’s a move to bolster this with electronic monitoring in longline fleets (which traditionally have low observer coverage). The WCPFC Scientific Committee evaluates these data annually to assess trends. For instance, they review CPUE indices for key sharks to infer if bycatch mitigation is working or if populations are still declining. WCPFC also maintains a Shark Research Plan to guide research priorities (such as stock assessments, tagging studies, and mitigation research) and periodically reviews the effectiveness of existing shark measures.

- Cooperation and capacity building: WCPFC works in concert with other tuna RFMOs and international agreements to ensure coherent shark conservation efforts. Many WCPFC measures mirror those in IATTC (Eastern Pacific) and ICCAT (Atlantic) so that shark protections are ocean-wide. The Commission also supports member countries, especially Small Island Developing States, by providing training and resources – for example, workshops on shark handling and identification, funding for national shark management plans, and sharing of best practices. This helps elevate the level of compliance and awareness across all fleets, large and small.

Key measures: CMM 2010-07 (Sharks, as amended by CMM 2014-05) and species-specific measures (CMM 2011-04 Oceanic Whitetip; CMM 2012-04 Whale Shark; CMM 2013-08 Silky Shark) form the regulatory backbone for shark bycatch mitigation in WCPFC. These are updated as needed in line with scientific advice.

Data needs and next steps

- Enhanced monitoring and compliance: A top priority is increasing the observer coverage on longline vessels and expanding electronic monitoring. Many shark interactions currently go unobserved due to low coverage, which means we may be underestimating bycatch and compliance issues (like illicit finning). By moving toward 20% or higher coverage (or camera systems on 100% of vessels), WCPFC can gather more accurate data on shark catches and ensure vessels are following no-retention and finning bans. Additionally, strengthening port inspections and cross-verification (inspecting vessels for hidden shark fins, etc.) will improve compliance.

- Shark stock assessments and indicators: There is a need for regular, up-to-date stock assessments for key shark species. Where full assessments are not feasible due to data gaps, the use of alternative methods (e.g., empirical trend analysis or demographic risk assessments) should be continued. For instance, conducting a South Pacific blue shark assessment, updating the North Pacific mako assessment, and initiating assessments for data-poor species like bigeye thresher or hammerheads are on the scientific agenda. The Shark Research Plan (2021–2025) outlines these, and securing the necessary data (through improved reporting and historical catch reconstruction) is critical to support them.

- Mitigation research and innovation: WCPFC will benefit from further research into shark bycatch reduction techniques. This includes testing gear innovations like hook shield devices (that prevent sharks from biting hooks), weak hooks (that allow large sharks to escape), or repellents (such as magnetic or electropositive materials). While some trials have been done, more work is needed to find solutions that work in WCPO fisheries without unduly impacting target catches. The Commission can promote pilot projects and collaborate with industry and scientists to develop and implement effective mitigation tools, especially for species like silky sharks or oceanic whitetips in longlines.

- Species-specific safe release guidelines: Continue the development and adoption of formal safe release guidelines for sharks (similar to those developed for manta rays). By CMM requirement, guidelines for handling oceanic whitetip and silky sharks have been under discussion – finalizing these and training crews in their use will standardize best practices across all fleets. As new information on post-release survival becomes available (e.g., via tagging studies), these guidelines should be refined to maximize the chances that released sharks survive.

- Integrated management and ecosystem approach: WCPFC is exploring more holistic management approaches that consider the cumulative impacts on shark populations. This might involve setting explicit catch or mortality limits for certain sharks across the entire Commission area (instead of the current patchwork of measures), and integrating shark conservation goals with those for target species (since, for example, fishing effort reductions on tuna can also benefit sharks). The Ecosystem and Bycatch Working Group within WCPFC will likely play a role in recommending how shark bycatch management can be better woven into overall fishery management plans, ensuring the ecosystem (predator-prey relationships, etc.) remains balanced. Collaboration with coastal states on protecting critical habitats (nurseries, aggregation sites) for sharks is also a next step that bridges WCPFC’s high-seas mandate with nearshore conservation.

Intersessional working group to develop a draft comprehensive shark CMM (IWG-Sharks)

- At WCPFC14 (December 2017) the Commission agreed to form an intersessional working group to develop a draft comprehensive shark CMM for discussion at WCPFC15 (IWG-Sharks). The IWG-Sharks was to primarily work virtually and will be formed through the issuance of a Circular from the WCPFC Secretariat inviting all parties to nominate representatives to participate in the activities of the group. The IWG-Sharks was chaired by Mr Shingo Ota (Japan).

- WCPFC14 agreed that the first phase of work will begin with the IWG Chair codifying WCPFC’s existing shark measures, taking into account comprehensiveness, and distributing this draft to participants by the end of February 2018. The IWG Chair will request that comments on the codified draft, as well as contributions on new elements, from IWG-Sharks participants be received by the end of March 2018. The IWG Chair will then compile these comments on the codified draft and new elements into a revised draft, requesting technical advice as necessary, and circulate it to IWG-Sharks participants on a timeline to be determined by the IWG Chair, giving due consideration to the timelines for SC14 and TCC14.

- At WCPFC15 (December 2018), the output from the IWG-Sharks was presented, and further deliberations took place in the margins of WCPFC15 through a SWG on Shark CMMs. The Commission tasked TCC15 with considering the outputs of the shark intersessional working group and encouraged interested Members to submit proposals to TCC15.

- Copies of the various drafts developed by the IWG-Sharks through 2018, and the draft that was prepared by the SWG Chair on Shark CMMs during WCPFC15, are provided here.