The WCPFC's goal is to manage Pacific tuna fisheries in a way that keeps them both productive and ecologically balanced over the long term. Instead of only trying to avoid a sudden collapse of fish populations, the WCPFC focuses on maintaining fish stocks at levels that maximize sustainable catches while protecting the marine ecosystem.

Record-Breaking Tuna Catch in 2024 (based on most recent available data; non-provisional)

In 2024, the WCPFC recorded its highest-ever tuna catch in the Convention Area, reaching an estimated 3.059 million metric tonnes (mt), surpassing both the 2023 total and the previous record set in 2019. Most of this catch came from the purse seine fishery, which contributed 70%, followed by longline (8%), pole-and-line (5%), and the rest (17%) from troll and small-scale coastal fisheries, especially in countries like Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam.

This massive harvest represented 85% of all tuna caught in the Pacific Ocean and over half (56%) of the global tuna catch. Notably, more than 80% of the tuna catch in this region came from the waters of coastal states, highlighting their central role in global tuna supply.

Sustainable Management

The WCPFC relies on science to set fishing limits that ensure we harvest fish at a rate the ocean can naturally replace, aiming for long-term productivity rather than short-term gains. To achieve this, experts conduct thorough assessments of major tuna species using data collected by observers and fishing vessel captains, as well as data collected through a range of monitoring programmes.

Extensive Data Collection

Scientists gather millions of data points on fish catches and fishing vessel activities, including details about the number of fish that are caught, their sizes, and ages. This large dataset ensures a clear picture of the current state of the tuna populations.

Monitoring Fishing Efforts

Information is collected from logbooks maintained by vessel captains satellite tracking systems, and data collected by fisheries observers. These methods help determine how much fishing is happening and where, offering insight into fishing pressures across the ocean.

Fish Tagging Programs

WCPFC members support an extensive tuna tagging programme where the tagging of individual fish allows researchers to monitor their movements across vast areas. This information helps in understanding migration patterns and how different regions contribute to the overall health of the populations.

Advanced Computer Models

Using sophisticated computer models, scientists estimate the current population sizes by comparing them to historical data. These models also simulate how various management measures might influence future population health.

Future Projections

By analyzing this wealth of data and modeling different scenarios, researchers can predict the potential impacts of management decisions. This helps ensure that any changes made will support the long-term sustainability of the fish stocks.

Overall, these scientific assessments allow the WCPFC to set informed fishing limits that balance the need for productive fisheries with the necessity of maintaining a healthy and resilient marine ecosystem.

The scientists at the Pacific Community's Oceanic Fisheries Programme provide scientific research and advice to the WCPFC. Their extensive knowledge and experience with studying Pacific Ocean fisheries and the ecosystems that support them, means that the WCPFC is receiving the best available science, a key principle to support WCPFC's objective.

Click here to learn more about the scientific research taking place at SPC.

Latest Stock Status

As of 31 December 2025.

| Stock | Latest Assessment | Overfished | Overfishing |

| WCPO Tuna | |||

| Bigeye tuna Thunnus obesus | 2023 (SC19) | No | No |

| Yellowfin tuna Thunnus albacares | 2023 (SC19) | No | No |

| Skipjack tuna Katsuwonus pelamis | 2025 (SC21) | No | No |

| South Pacific albacore tuna Thunnus alalunga | 2024 (SC20) | No | No |

| Northern Stocks | |||

| North Pacific albacore Thunnus alalunga | 2023 (SC19) | No | No |

| Pacific bluefin tuna Thunnus orientalis | 2024 (SC20) | No | No |

| North Pacific Swordfish Xiphias gladius | 2023 (SC19) | No | No |

| WCPO Billfish | |||

| Southwest Pacific swordfish Xiphias gladius | 2021 (SC17) | No | No |

| Southwest Pacific striped marlin Kajikia audax | 2019 (SC15) | Likely | No |

| North Pacific striped marlin Kajikia audax | 2023 (SC19) | Yes | Yes |

| Pacific blue marlin Makaira nigricans | 2021 (SC17) | No | No |

| WCPO Sharks | |||

| Oceanic Whitetip Shark Carcharhinus longimanus | 2019 (SC15) | Yes | Yes |

| Silky shark Carcharhinus falciformis | 2024 (SC20) | Uncertain | No |

| South Pacific blue shark Prionace glauca | 2021 & 2022 (SC17 & SC18) | No | No |

| North Pacific blue shark Prionace glauca | 2022 (SC18) | No | No |

| North Pacific shortfin mako Isurus oxyrinchus | 2024 (SC20) | No | No |

| Pacific bigeye thresher shark Alopias superciliosus | 2017 (SC13) | N/A | N/A |

| Southern Hemisphere Porbeagle shark Lamna nasus | 2017 (SC13) | N/A | Very low |

| Whale Shark Rhincodon typus | ‘PS Risk’ 2018 (SC14) | N/A | N/A |

| Southwest Pacific shortfin mako shark Isurus oxyrinchus | 2022 (SC18) | Unknown | Unknown |

Latest Stock Status Summary for Each Key Tuna Species

(Tuna Fisheries Assessment Report)

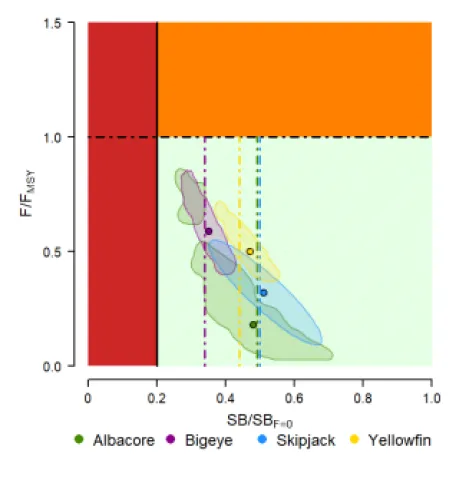

"Majuro Plot"

Understanding a Majuro Plot

In essence, the x-axis tells us about the current health or remaining size of the fish stock, while the y-axis shows whether the current fishing pressure is too high or within a sustainable range.

Y-axis (Fishing Pressure):

The y-axis shows how heavily the fish stock is being fished. It compares the current fishing level to the ideal level that would allow the highest sustainable catch over the long-term without running down the stock.

If the point is high on the y-axis, it means fish are being caught too quickly, which could lead to overfishing.

X-axis (Depletion):

The x-axis shows a kind of "health meter" for the fish stock. It indicates how much of the stock remains compared to a situation where no fishing has ever taken place. If the point is farther to the left, it means more fish have been removed by fishing. When the stock drops below a critical level, it is considered depleted or overfished, meaning it may be hard for the stock to recover.

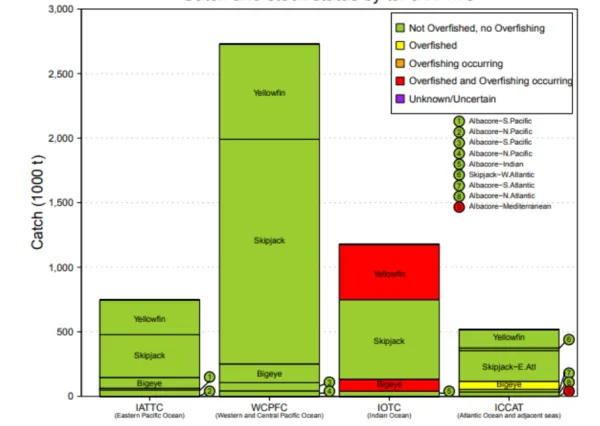

Catch and Stock Status Comparison of Tuna RFMOs

The western and central Pacific tuna fishery: 2024 overview and status of stocks (publication of the Pacific Community)

Long Term Productivity

Long term productivity means ensuring that fish populations continue to thrive over many years, not just in the short run. By managing the fish stocks carefully, the WCPFC ensures that the fisheries can continue to be a reliable resource. We work to keep the fish populations at an optimal level that maximizes benefits for both current and future generations, meaning that the ocean remains a viable source of food and economic activity over time.

Sustainable Regeneration

The focus is on maintaining fish stocks at levels where they can naturally reproduce and grow. This careful management helps to avoid overfishing, ensuring that there are always enough mature fish to sustain the population year after year.

Reliable Resource for Communities

By keeping fish populations healthy, fisheries remain a dependable source of food and income. This reliability benefits fishing communities and economies that depend on the ocean, making sure they are supported now and in the future.

Balanced Harvesting

Optimal management means setting fishing limits that balance the immediate needs of the industry with the long term health of the ecosystem. This approach maximizes the benefits from the fisheries without depleting the resource, preserving the ocean’s natural productivity.

Ecosystem Considerations

Long term productivity isn’t just about the fish themselves. It also involves protecting the broader marine environment. Healthy ecosystems contribute to the stability of fish populations by providing crucial habitats and food sources.

Economic and Food Security

Ensuring that fisheries remain productive means that the ocean continues to be a viable source of food and economic activity. This long term approach helps prevent sudden collapses in fish stocks, which could lead to food shortages and economic hardships.

In summary, by managing fish stocks carefully, the WCPFC works to maintain an environment where fisheries can continuously provide resources and support economic stability for both today’s communities and future generations.

Ecosystem Health

"Ecosystem Health" in fisheries management means looking after the entire marine environment rather than focusing solely on one species. This approach recognizes that all parts of the ocean—every species, habitat, and natural process—are interconnected and contribute to the overall balance of the ecosystem.

Holistic Management

The WCPFC's strategies consider the full web of marine life. Instead of managing just the target fish species, we also account for other creatures and habitats that play crucial roles in the ecosystem, such as turtles, sharks, and seabirds. This helps ensure that changes in one part of the system don’t lead to unforeseen problems in another.

Preventing Unintended Consequences

When only a single species is managed without regard for the broader ecosystem, actions such as overfishing or habitat disruption can have ripple effects. For example, reducing a key species might affect predators that rely on it or disturb the balance of species that compete for resources. The approach of preserving ecological integrity helps avoid these kinds of unintended impacts.

Maintaining Natural Processes

A healthy ecosystem supports all natural processes, such as breeding, feeding, and migration. By keeping the entire system intact, the strategies ensure that these processes continue as they should, which is essential for the long-term sustainability of marine life.

Resilience to Change

A well balanced ecosystem is better able to withstand disturbances, whether from environmental shifts, pollution, or other stresses. Protecting the ecosystem in its entirety helps maintain its ability to recover from such changes, which is critical for both the environment and the communities that depend on it.

In essence, the focus on ecosystem health means making decisions that protect the complete network of marine life, ensuring that the ocean remains productive, resilient, and balanced over the long term.

Optimum Yields

The goal is to achieve the best possible long-term catch (or yield) without harming the overall health of the ocean. It’s about finding that sweet spot where fishing remains productive, but the ocean’s natural balance isn’t upset. Optimal yields aim to balance the immediate benefits of fishing with the long-term health of the fish populations and the surrounding marine ecosystem. To achieve this balance, the WCPFC is developing harvest strategies that include setting science-based targets and limits.

Science Based Targets

Managers establish target reference points that represent the ideal level of fish biomass, where the population is large enough to support both a healthy ecosystem and sustainable harvests. These targets help define what an optimal yield looks like over the long term.

Limits and Precaution

In addition to targets, there are also limit reference points. If a fish stock nears or falls below these limits, harvest levels are reduced or even halted to prevent further decline. This precautionary approach ensures that fishing activities do not compromise the ecosystem's natural balance.

Adaptive Management

Harvest strategies are designed to be flexible. They incorporate regular monitoring of fish stocks and the marine environment, so that if conditions change, whether due to environmental factors or shifts in fish populations, fishing limits can be adjusted accordingly. This adaptive approach helps maintain optimal yields despite uncertainties.

Long Term Focus

The ultimate goal is to sustain the productive capacity of the fisheries. This means that even as fish are harvested, the management practices in place ensure that the populations remain robust enough to continue reproducing and supporting the ecosystem. Over time, this balance between catch and conservation is what allows the ocean to be both a reliable food source and a healthy environment. In summary, optimal yields are achieved by setting clear targets and limits based on scientific assessments and by adjusting management practices as needed. This balanced strategy ensures that fishing remains productive while safeguarding the ocean’s natural processes and long term vitality.