🐦 WCPFC Seabird Bycatch Mitigation Terms

This guide describes key practices and tools the WCPFC uses to reduce seabird bycatch, particularly for threatened albatrosses and petrels. These terms are found in conservation measures and seabird bycatch mitigation guidelines.

📘 Definitions and Measures

Bird-Scaring Lines (Tori Lines): Streamer lines deployed from the stern of fishing vessels to deter birds from approaching baited hooks. Brightly colored streamers flapping over the baited hook line scare seabirds (especially albatrosses) away until the hooks sink beyond their reach. Properly designed tori lines with adequate length and drag significantly reduce seabird attacks on bait during line setting.

Branch Line Weighting: Adding weights to branch lines (the secondary lines with hooks) to make baited hooks sink faster. Common practices include using weighted swivels or clips (e.g. ≥60 g weight within 1 m of the hook). Faster sinking means less time when birds can snatch the bait at the surface, thereby lowering seabird hookings.

Night Setting: Setting longlines during hours of darkness (typically at least one hour after dusk until one hour before dawn). Many seabirds, particularly albatrosses, are less active or less able to see baits at night, especially if deck lighting is minimized. Night setting, often combined with moon phase considerations and low lighting, can dramatically reduce seabird interactions.

Side-Setting with Shields: A longline setting technique where gear is deployed from the side of the vessel (rather than the stern) with a physical or water curtain to block birds’ view of baited hooks. By the time the hooks move astern, they are already deeper in the water. This method, pioneered in some fleets (e.g. Hawaii), has been shown to reduce seabird catch when properly implemented alongside bird curtains and weighted lines.

Hook-Shielding Devices: Technologies that encase or cover the point and barb of a hook until it sinks to a certain depth (e.g. 10–20 m). Examples include hook pods and capsules that automatically open underwater. These devices prevent seabirds from getting hooked during line setting, virtually eliminating bird interactions with baited hooks at the surface. They are an emerging mitigation option recognized by WCPFC.

Seabirds in the WCPO

The Western and Central Pacific Ocean (WCPO) is home to many species of albatrosses and petrels, several of which are threatened or endangered. These seabirds roam vast distances across ocean basins and often forage in the same areas where tuna fisheries operate. Unfortunately, they are vulnerable to being accidentally caught (bycatch) in longline fisheries when they seize baited hooks and drown. Because albatrosses and large petrels are long-lived and reproduce slowly, even small amounts of bycatch can cause population declines. WCPFC’s conservation measures for seabirds focus on preventing birds from getting hooked in the first place, through the use of deterrent devices and fishing practice modifications.

WCPFC addresses seabird bycatch primarily by requiring mitigation measures on longline vessels operating in areas where seabirds are most at risk. All longliners fishing in specified latitude zones must deploy some combination of bird-scaring lines, weighted branch lines, night setting, or other approved measures to reduce seabird interactions. These measures have proven effective in significantly lowering the catch rates of albatrosses and petrels without hindering fishing success. By implementing best practices – and continually improving them with input from seabird experts – the WCPFC aims to minimize seabird mortality in its fisheries. Ongoing monitoring and international collaboration (e.g. with ACAP and BirdLife International) are key to refining these actions and ensuring populations of vulnerable species can recover.

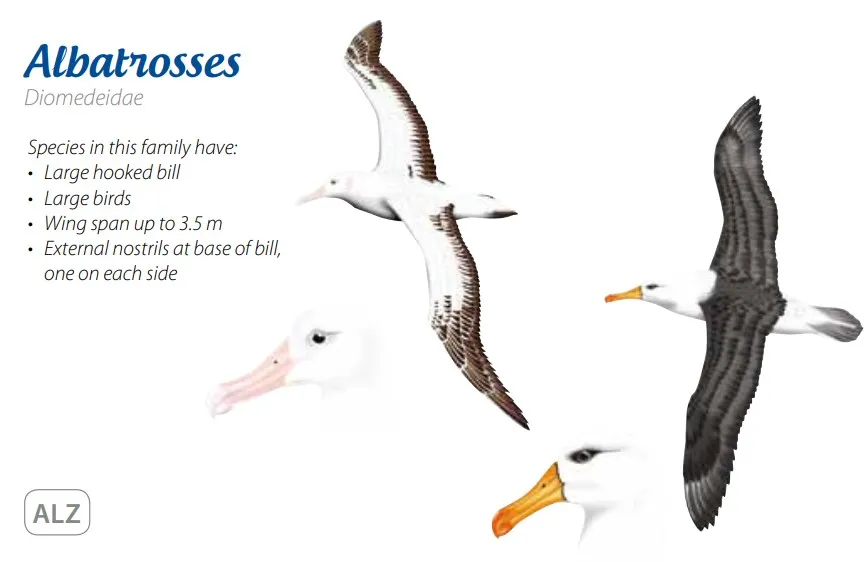

Albatrosses

Latest assessment | 2022 ACAP trends analysis; 2020 IUCN Red List update |

Status | Highly threatened overall. Of 17 albatross species in the WCPO, the majority are classified as threatened (Endangered or Vulnerable) or Near Threatened. Albatrosses are among the most endangered bird groups globally due to adult mortality from fisheries bycatch:. Only one or two albatross species are considered Least Concern, and even those face ongoing risks. |

Key findings | Albatross populations are extremely vulnerable to increases in adult death rates. They are long-lived and breed slowly (most raise one chick every one or two years), so even low levels of bycatch can cause population declines. Over half of albatross species overlapping the WCPFC area are still in decline, prompting ACAP to declare a “Conservation Crisis” for albatrosses in 2019. On a positive note, intensive mitigation in some fisheries (e.g., around Hawaii and New Zealand) has stabilized or slightly increased certain albatross populations in recent years. |

Management | WCPFC’s seabird measure (CMM 2018-03) prioritizes albatross conservation. Longline vessels operating in high-risk latitude zones for albatross (south of 30°S and north of 23°N) must deploy multiple bycatch mitigation methods on every set. Approved measures include bird-scaring (tori) lines, branch line weighting, night setting, or hook-shielding devices, used in combination. These requirements, based on ACAP best practices, have significantly reduced albatross bycatch where rigorously implemented. Compliance is monitored through observer programs and annual reports on mitigation use. |

Range and threats

- Albatrosses roam vast areas of the Pacific, often concentrating in productive zones where fisheries operate. This overlap has historically led to significant bycatch: roughly two-thirds of global seabird longline mortalities are estimated to occur in the North Pacific (above ~20°N), and about one-quarter in the far South Pacific (south of 30°S). These regions correspond to where Laysan, Black-footed, and other albatrosses forage in the north, and where species like Wandering and Shy Albatross forage in the south. Without mitigation, thousands of albatrosses were being killed annually in these fisheries.

- Even small increases in adult mortality can crash albatross populations. For example, ACAP identified the Antipodean Albatross (endemic to New Zealand) as facing an extreme decline – about 5% fewer adults each year – primarily due to females getting caught on longline hooks. Models predict that if current bycatch levels continue, this albatross could decline by over 80% in one generation. Similar trends have been observed in other albatross species, underscoring how critical it is to prevent every possible fatality of these slow-breeding birds.

- International cooperation is key. Albatross migrations span multiple jurisdictions – for instance, a single albatross may feed in the high seas, in WCPFC waters, and in the Eastern Pacific (IATTC area) during one year. To protect them throughout their range, WCPFC collaborates with ACAP and other RFMOs via formal agreements (an ACAP–WCPFC Memorandum of Understanding was signed in 2007). This ensures consistent bycatch mitigation measures across ocean basins. Data on albatross movements and bycatch is shared internationally so that conservation actions (such as mitigation requirements or area closures) can be synchronized for maximum benefit.

Mitigation and best practices

- Multiple deterrents at once: Experience has shown that using a combination of mitigation measures is far more effective than any single measure alone. For example, setting lines at night *and* using properly designed tori lines *and* weighted hooks provides three layers of protection – greatly reducing the chance an albatross can grab a bait. ACAP’s best-practice advice recommends this integrated approach, and WCPFC rules require at least two measures in core albatross habitat areas. Where fleets (such as the Hawaii longline fishery) have adopted these measures, albatross bycatch has dropped dramatically, demonstrating that “doing it all” pays off in near-zero seabird catches.

- New technologies: In recent years, novel mitigation technologies have emerged. One example is hook-shielding devices – essentially sleeves or capsules that cover the hook and bait until it sinks to a preset depth (e.g., 10–20 m). These devices prevent any bird (albatross or otherwise) from accessing the hook near the surface. WCPFC now recognizes hook-shielding devices as an alternative stand-alone measure to meet mitigation requirements. Trials have shown they virtually eliminate seabird hookings at the surface. Other innovations include underwater bait-setting machines (to deploy hooks below the surface), and smart weighted lines that sink extremely fast. WCPFC keeps its measures under review to incorporate proven new methods; for instance, if a technology like an underwater setter becomes practical for broad use, it could be added as an approved mitigation option in the future.

- Crew training and compliance: Ensuring that mitigation measures are not only available but correctly used is crucial. WCPFC member countries conduct training workshops and outreach for vessel operators on how to implement seabird bycatch measures. This includes showing crews how to rig and deploy tori lines at the proper height and distance, how to handle weighted lines safely, and why it’s important to avoid excess lighting or offal discharge during night sets. Observers and electronic monitoring systems actively check that vessels are using the required measures and using them properly. High compliance is rewarded by sharply lower bycatch rates – for example, on vessels that strictly follow all guidelines, it’s not uncommon to go an entire fishing season with zero albatrosses caught. Conversely, if a vessel fails to deploy mitigation (or does it incorrectly), observers often document higher seabird attendance and occasional captures, reinforcing the need for constant diligence.

Monitoring and research

- Improved bycatch data: The WCPFC Scientific Committee has highlighted the need for better data to evaluate seabird bycatch trends. In response, WCPFC adopted new reporting guidelines so that all members report seabird interactions in a standardized way (including details like species ID and which mitigation was in use). Observer coverage is being incrementally increased, and electronic monitoring (cameras on boats) is being introduced to supplement human observers, especially in fleets with low coverage. These steps help scientists get a more accurate estimate of total albatross mortality and assess which fisheries or areas might need additional attention. They also enable analysis of mitigation effectiveness – for instance, comparing bycatch rates before vs. after the 2018-03 measure to ensure it’s achieving the expected reductions.

- Population monitoring: Outside of fisheries, researchers continually monitor albatross breeding colonies to track population health. On important breeding islands (such as in Hawaii, Japan, New Zealand), annual or periodic counts of nesting pairs, as well as banding and re-sighting programs, provide insight into survival and breeding success. ACAP compiles these data to produce species assessments and trend analyses. If bycatch mitigation is working, one would expect to see adult survival rates improve and population declines slow or reverse over time. Some albatross populations (e.g., Laysan Albatross on Midway Atoll) have indeed shown stable or increasing trends in the last two decades, coinciding with intensive bycatch prevention efforts. Continued monitoring is essential to detect any negative changes early. It also helps identify emerging threats – for example, if a population is not recovering despite low reported bycatch, factors like climate change or pollution might be investigated.

- Collaboration and future research: Albatross conservation in the WCPO is part of a larger global effort. WCPFC works closely with other RFMOs and conservation bodies. ACAP’s Seabird Bycatch Working Group provides updated technical advice every few years, which WCPFC considers for refining its measures. Collaborative research, such as tagging studies, helps to map albatross migrations with ever greater precision – critical for predicting overlap with fisheries. Looking ahead, there is interest in habitat modeling to predict how oceanographic changes (e.g., shifting currents or warming seas) might alter albatross foraging ranges, which could in turn require adaptive management by WCPFC. By staying proactive and science-based, the goal is to keep strengthening bycatch mitigation so that albatross populations not only stop declining but begin to recover throughout the Pacific.

Source documents: ACAP (2022) status and bycatch advice; IUCN Red List (2020); WCPFC CMM 2018-03 and implementation reports (2018–2024).

Boobies and Gannets

Latest assessment | 2020 IUCN Red List evaluations; regional monitoring |

Status | Not threatened. The predominant booby species in the WCPO (e.g. Red-footed, Brown, and Masked Boobies) are all listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List, reflecting their relatively large and stable populations. Gannets in the region (such as the Australasian Gannet in the southwest Pacific) are also not globally threatened. These birds have not experienced significant declines attributable to fishing; they were classified as “not vulnerable” to longline fisheries in regional risk assessments. |

Key findings | Boobies and gannets are diurnal plunge-divers that mostly inhabit coastal and island environments. They feed by diving into surface waters to catch fish and squid, and generally do not venture far into the open ocean away from breeding sites. Because of this behavior and distribution, their interaction rate with pelagic longline fisheries is very low. Observations indicate that while boobies will occasionally follow fishing vessels (especially near breeding islands) and may attempt to snatch baits, they are rarely hooked or entangled. No boobies or gannets in the WCPO are experiencing population decline due to fisheries – their main threats are more related to habitat (predation at colonies, human disturbance, etc.), rather than bycatch. |

Management | WCPFC’s seabird measures historically focused on latitudes where albatrosses and petrels occur, and did not mandate specific mitigation in equatorial waters where boobies are common. Even under the updated CMM 2018-03, the tropical band (roughly 25°S–23°N) is exempt from required measures – vessels there are only encouraged to deploy a mitigation method. This approach reflects the consistently low bycatch rates for boobies and gannets. Nonetheless, general provisions apply: any seabird (including boobies/gannets) caught alive must be released, and fishers are expected to avoid unnecessary harm to all seabirds. Some members voluntarily apply measures (like tori lines or weighted hooks) in tropical fisheries as a precautionary best practice, even when not obligated, to ensure these birds remain safe. |

Ecology and interactions

- Boobies (family Sulidae) are abundant in tropical Pacific regions, breeding on remote islands and foraging primarily in nearby waters. Species such as the Red-footed Booby, Brown Booby, and Masked Booby are commonly seen around coral atolls and archipelagos, where they feed on schooling fish driven to the surface by predators. These birds can travel tens or even hundreds of kilometers from their nesting colonies to find food, but they usually remain within range of land to roost at night. Gannets (closely related to boobies) have a similar ecology in subtropical areas – for example, the Australasian Gannet forages on continental shelf waters around New Zealand and southern Australia. Because of this coastal/nearshore foraging pattern, boobies and gannets infrequently encounter tuna longline vessels, which often operate far offshore. This limited overlap is a primary reason why their bycatch is very low.

- In terms of behavior, boobies and gannets hunt by sight during daylight. They locate prey from the air and dive steeply into the ocean at high speed to catch fish below the surface. Unlike albatrosses or petrels, they do not typically scavenge behind fishing vessels for offal (though they may pick up discarded bycatch on occasion). They also have the ability to fully submerge and swim briefly underwater when pursuing prey. These traits mean that a baited longline hook, which is attached to a moving vessel and sinks beneath the surface, is not an easy target for a booby. Indeed, fisheries data indicate that boobies and gannets rarely get hooked – they either ignore the moving baits or fail to get the bait off the hook before it sinks. In one study, Pacific longline skippers reported only occasional interactions with boobies, mostly involving curious Brown Boobies grabbing trolled bait scraps without getting snagged. Such incidents were minor and almost never resulted in injury to the bird.

- Recorded bycatch instances are extremely scarce. Over 2007–2016, WCPFC observers documented nearly 1,000 seabirds caught in longline fisheries, the vast majority being albatrosses and petrels, and zero boobies or gannets among those records. In the purse seine fishery (which operates in equatorial waters where boobies reside), only 15 seabird captures were recorded in the same ten-year period. Those few incidents likely involved boobies diving into nets or roosting on fishing gear; all available evidence suggests such events are exceptionally rare. This aligns with observations that boobies/gannets are adept fliers and can evade danger – they are often seen flying around purse seine nets to snatch small fish, but quickly retreat once the net starts to close. Overall, their natural wariness and the brief exposure of fishing gear at the surface translate into a very low risk of entanglement or hooking for these birds.

Mitigation and oversight

- Leverage existing measures: Although no special rules target boobies and gannets, the general seabird-safe fishing practices promoted by WCPFC also benefit these birds. For instance, skippers are encouraged to avoid chumming or dumping fish waste while setting lines, especially in areas where any seabirds are present. This is a simple step that can prevent attracting boobies to the vessel. Similarly, if a vessel happens to be fishing near an island colony (where boobies might be feeding), using a tori line or weighted hooks – even if not mandated – provides an extra safeguard. Since these mitigation tools are already on hand for use in higher latitudes, many fishermen apply them opportunistically in the tropics when they notice bird activity. This voluntary uptake helps keep booby/gannet bycatch near zero.

- Safe release and reporting: WCPFC’s guidelines for handling bycaught seabirds apply equally to all species. In the uncommon event that a booby or gannet is hooked or entangled, crew are instructed to gently bring the bird onboard (if it’s safe to do so) and remove the hook or line using a de-hooker or line-cutter, then release the bird in a recovered condition. Because boobies have relatively small bills (compared to albatrosses), they are easier to handle without injury; many fishermen are familiar with freeing them from recreational hooks near shore. These events are so rare in WCPO fisheries that they’re mainly anecdotal, but the principle is clear: every effort should be made to release the bird unharmed. Additionally, any such interaction must be recorded in the logbook and reported. By maintaining this documentation, WCPFC can detect if booby/gannet interactions start rising for any reason. To date, the consistently low reports confirm that current practices are effective in avoiding harm to these species.

- Future considerations: While boobies and gannets are not currently impacted by WCPO tuna fisheries, WCPFC remains vigilant. If climate change or ecosystem shifts lead these birds to range more widely offshore (potentially increasing overlap with fisheries), the Commission can adapt its measures. For example, if a particular area or season saw increased booby activity around fishing vessels, WCPFC could consider extending mandatory mitigation into that area/season. The Commission’s precautionary approach and cooperation with experts (like BirdLife International and ACAP) ensure that even species not presently at risk stay on the radar. In essence, the absence of a problem now doesn’t preclude action later if needed. Fortunately, boobies and gannets in the Pacific are currently faring well, and continued monitoring – both at colonies and at sea – will help keep it that way.

Source documents: IUCN Red List (2020) – status of tropical seabirds; WCPFC observer data (2007–2016) and SC analyses (Pacific Islands seabird bycatch risk); WCPFC seabird measure (2018-03) tropical provisions.

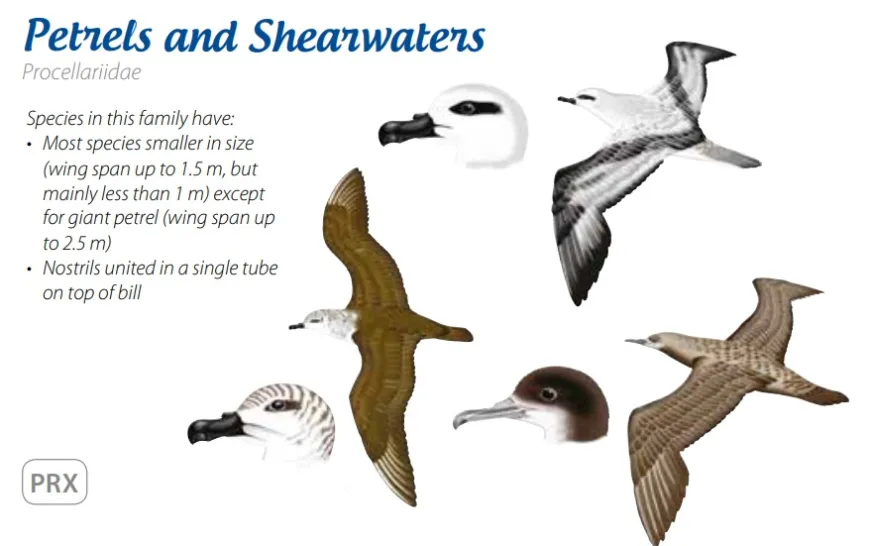

Petrels and Shearwaters

Latest assessment | 2019–2022 ACAP species assessments; 2020 IUCN Red List |

Status | Several threatened species. The WCPO supports many petrel and shearwater species, ranging from abundant to critically endangered. Notably, six ACAP-listed “large petrel” species forage in this region. Among these, the Westland Petrel (Procellaria westlandica) is Endangered (only ~6,000 breeding pairs at one New Zealand site), and the Black Petrel (P. parkinsoni) is Vulnerable (~7,000 pairs on two NZ islands). The White-chinned Petrel – one of the most numerous (over a million pairs) – is still classified as Vulnerable due to ongoing declines from fisheries bycatch. In addition, several shearwaters (e.g. Flesh-footed, Pink-footed) are Near Threatened. Overall, petrels and shearwaters constitute a high-risk group: they account for a large portion of reported seabird bycatch and include species with very small, vulnerable populations. |

Key findings | Petrels and shearwaters are highly susceptible to longline bycatch because of their foraging behavior. Many are aggressive, pursuit-diving feeders – they will seize baited hooks at the surface or even dive deep to retrieve sinking bait. Studies show some medium-sized petrels can dive 10–20+ meters underwater, easily reaching hooks before they sink beyond danger. Large Procellaria petrels (Black, Westland, White-chinned, etc.) are particularly adept and have been dubbed “worst offenders” in thwarting mitigation measures. Consequently, these species suffer significant mortality in longline fisheries worldwide, and population declines have been observed in parallel. For example, White-chinned Petrels – though still numerically abundant – are declining at several colony sites, likely due to cumulative bycatch across fleets. Smaller shearwaters (e.g., Wedge-tailed Shearwater) are less frequently caught, as they feed more on live prey and may not target longline bait as aggressively. However, any shearwater or petrel will take an easy meal if available, so none are completely immune from risk. |

Management | WCPFC’s seabird mitigation measures cover most areas where petrels and shearwaters are at risk. South of 30°S – where species like White-chinned and Grey Petrels forage – vessels must use two mitigation methods (or hook-shielding devices) at all times. Furthermore, starting in 2020, in the zone 25°S–30°S at least one measure is required year-round. These requirements greatly lessen bycatch in the southern temperate zone. However, some threatened petrels range into lower latitudes not fully covered by mandatory measures: for instance, the Black Petrel migrates into equatorial seas north of New Zealand, within 25°S–23°N where mitigation is only encouraged. To address such gaps, certain WCPFC members (e.g., New Zealand domestically, and some fleets voluntarily) have instituted extra protections like using mitigation in all seasons/areas irrespective of latitude. The Commission is also reviewing new information on petrel distribution to determine if expanded coverage of the seabird CMM is warranted in the future. |

Range and interactions

- Petrels and shearwaters occupy diverse niches across the Pacific. Some, like the Wedge-tailed Shearwater or Tropical Shearwater, breed on tropical islands and forage near those regions year-round. Others are long-distance migrants: the Black Petrel, for example, breeds in New Zealand but spends its non-breeding season in the eastern tropical Pacific (off South America), crossing the breadth of the WCPO in the process. Large petrels of the genus Procellaria (Black, Westland, White-chinned, Grey Petrel) mostly breed in the New Zealand region and forage widely in the South Pacific, often in sub-tropical and temperate waters where tuna and swordfish longline effort is significant. Wherever these birds overlap with baited longlines, there is potential for bycatch. Petrels and shearwaters are bold and often feed in groups; a single longline set can attract dozens of them. This group also includes strong divers – for instance, Black Petrels have been recorded diving to at least 38 meters depth. Their diving ability means that even night setting or quick-sinking baits can sometimes be intercepted. Indeed, in the absence of comprehensive mitigation, petrels/shearwaters (over ~500 g) have proven to be the most frequently caught seabirds in many fisheries.

- Certain “hotspot” areas have been identified for petrel bycatch. By analyzing observer data, scientists found high petrel catch rates in the vicinity of New Zealand and adjacent high seas – correlating with the foraging range of species like Westland and White-chinned Petrels. Another area of concern is the Humboldt Current region off South America (outside WCPFC’s area) where many Black Petrels and Pink-footed Shearwaters winter; bycatch there can impact the populations that breed in the WCPO. Within the WCPFC area, the highest mortalities occur south of 25°S (hence the emphasis on mitigation in those latitudes). Equatorial waters generally have fewer petrels (most tropical species like gadfly petrels are smaller and not as attracted to longlines), but there are exceptions – for example, Flesh-footed Shearwaters in the North Pacific subtropics have been caught in some fisheries. Overall, mapping petrel/shearwater distributions against fishing effort is an ongoing effort. ACAP and WCPFC members use tracking data and observer records to continually refine our understanding of where interactions are most likely, so that management can be targeted appropriately.

- A special note on Procellaria petrels: these large petrels are notorious in bycatch statistics. They are aggressive, surface-seizing birds that will dive and fight over baits, often defeating basic mitigation like single tori lines. They have even been observed pulling hooked fish or bait to the surface, which can cause a chain reaction of other birds getting hooked (so-called “secondary attacks”). All Procellaria species in the region (White-chinned, Black, Westland, Grey Petrel) are either Vulnerable or Endangered and have been prioritized for action by ACAP. Their behavior makes them challenging to protect – even well-implemented mitigation can occasionally fail if these petrels are abundant. This is why ACAP continually researches improved measures specifically with Procellaria in mind, and WCPFC members pay close attention to any rises in their bycatch rates.

Mitigation strategies

- Depth and sink rate matter: Since many petrels and shearwaters can dive to substantial depths, a key mitigation goal is to get hooks out of reach as fast as possible. ACAP recommends using weighted branch lines that ensure hooks sink beyond 10 m depth quickly, especially important given Black Petrels commonly dive >10 m and occasionally to ~40 m. In practice, this means adding sufficient weight (e.g., 60–120 g) near the hook. However, weighting alone is not enough – birds can still grab the bait in the few seconds before it sinks deeply. Thus, weights must be paired with bird-scaring lines (tori lines) to physically block birds from reaching the bait during those critical seconds, and/or night setting to make the bait harder to locate. The combination of these measures has proven effective: for example, experimental studies in New Zealand waters showed that when lines were both well-weighted and protected by tori lines, petrel catches dropped to very low levels. In short, an integrated approach is essential – a multi-pronged defense to keep determined diving birds at bay until the gear is safely deep.

- Hook-shielding devices: One of the promising newer tools for petrel bycatch prevention is the hook-shielding pod. By encapsulating the hook, these devices render the bait inaccessible during the entire duration of its drop through the danger zone. Petrels chasing the sinking bait simply cannot get the hook until it’s far below. WCPFC’s measure allows hook-shielding devices as a standalone alternative to using tori lines + weights. Trials, particularly with White-chinned Petrels in New Zealand’s fisheries, have shown near-zero seabird catches when every hook was shielded. The trade-off is the added cost and handling of the devices, but some fleets are beginning to adopt them for the added protection they offer. Alongside hook-shielders, other innovations like double-weighted lines (two weights per branch line to speed sinking) or dyeing baits blue (to make them less visible to birds) have been tested. While not all experiments show significant benefits, the suite of options gives fishermen flexibility to find what works best for their operation. WCPFC keeps an eye on these developments – any technique that consistently reduces petrel/shearwater mortality can be incorporated into future guidelines.

- Offal management and bait safety: One often overlooked factor in petrel bycatch is the attraction of fishing vessels due to offal (fish waste) discards. Petrels have an excellent sense of smell and are quickly drawn to vessels that are discharging fish heads, guts, or unused bait. If a flock of petrels is busy scavenging behind a boat, they are much more likely to notice and attack baited hooks during setting. Therefore, best practice is for vessels to retain offal during line setting and only release it once the setting is finished (or when no birds are around). Some vessels have equipment to macerate offal into tiny pieces, which is thought to reduce the incentive for birds to chase it. Ensuring that bait is properly thawed (so it sinks faster) and not throwing any bait overboard outside of the hooks on the line are additional precautions. These work in tandem with mandated measures: for example, even with a tori line out, if a vessel dumps a stream of fish waste, petrels might dive under the tori line to reach it and then also grab hooks. By minimizing attractants (like offal and garbage) and keeping a “clean” wake, fishermen can significantly reduce the number of birds that approach close to danger.

- Species identification and data: Because many petrels and shearwaters look alike, especially in the field, WCPFC has emphasized improving species identification in bycatch records. Observer training now includes identification of key petrels (for instance, differentiating a White-chinned Petrel from a Flesh-footed Shearwater, or a Black Petrel from a Westland Petrel). WCPFC, with ACAP’s help, developed seabird identification guides with photos and descriptions to aid this effort. Accurate data is crucial: if we know exactly which species are being caught and where, managers can tailor mitigation more precisely. For example, if observers report that nearly all petrel bycatch south of 40°S are White-chinned Petrels, that underscores the need to work with CCAMLR (the Antarctic fisheries body) as those birds move between WCPFC and CCAMLR areas. Likewise, if Black Petrels turn up in significant numbers in a certain fishery north of New Zealand, WCPFC can target that fishery for outreach and perhaps additional measures during the months Black Petrels are present. In summary, better identification and reporting lead to better conservation actions.

Monitoring and research

- Colony-based monitoring: Many petrels and shearwaters are endemic breeders on a limited number of islands, making colony monitoring vital for assessing population status. In New Zealand, for instance, both Black Petrel and Westland Petrel colonies are monitored annually or semi-annually – researchers count burrows, band adults and chicks, and check survival rates. Recent surveys suggest Black Petrel numbers have at least stabilized, likely owing to intensive predator control at the breeding sites and improved bycatch mitigation at sea. Westland Petrel may even be increasing slightly in number as of the latest census, which is an encouraging sign. These trends will be watched closely. Additionally, some of the most endangered tropical petrels (e.g., Fiji Petrel, which is Critically Endangered) are subjects of ongoing search and monitoring efforts; while such species are not known to be impacted by fisheries (they are so rare that bycatch has never been recorded), any information on their population trajectory is valuable. WCPFC members support on-the-ground conservation (through programs like the Pacific Islands Trust) recognizing that protecting breeding habitats complements at-sea measures.

- Tracking and telemetric studies: Advances in miniature tracking devices (satellite tags, GPS loggers, geolocators) have revolutionized our knowledge of petrel and shearwater movements. Researchers have tagged individuals of species like the Black Petrel, White-chinned Petrel, and Flesh-footed Shearwater to map their migratory routes and feeding areas. These studies have directly informed WCPFC discussions – for example, knowing that Black Petrels spend months off the coast of Peru/Ecuador has spurred increased data-sharing with IATTC (the Eastern Pacific RFMO) to ensure those birds aren’t facing unmitigated bycatch there. Likewise, tracking Westland Petrels revealed frequent use of seas east of New Zealand, leading that country to extend its domestic mitigation measures year-round in those waters (beyond WCPFC’s seasonal requirements). As tracking continues, we gain insight into how petrel distributions shift with ocean conditions; this will help WCPFC anticipate future bycatch hotspots. If, say, ocean warming pushes certain prey species further south, petrels might alter their range – managers could then proactively expand mitigation to new areas if needed.

- Collaboration and cross-treaty efforts: Petrels and shearwaters are a shared responsibility among many nations. WCPFC engages with ACAP’s working groups for technical guidance and with other RFMOs to ensure our measures are up to global standards. For instance, ACAP regularly updates its best-practice advice (e.g., recommending minimum sink rates for hooks, minimum tori line specifications) and WCPFC considers these updates for incorporation at Commission meetings. There is also collaboration through workshops and joint research projects. A recent example is a cooperative study on diving behavior of petrels in the WCPO, involving New Zealand and U.S. scientists, which has provided direct input on how deep hooks need to be protected. WCPFC also looks to domestic initiatives like Australia’s and New Zealand’s seabird bycatch plans for inspiration on improving compliance and innovation. Through these multi-organization efforts, the gap between science and management is narrowed, ultimately benefitting the conservation of petrels and shearwaters across the Pacific.

Source documents: ACAP (2019 & 2022) species status reports; IUCN Red List (2020); WCPFC Scientific Committee papers on seabird bycatch mitigation and diving behavior.

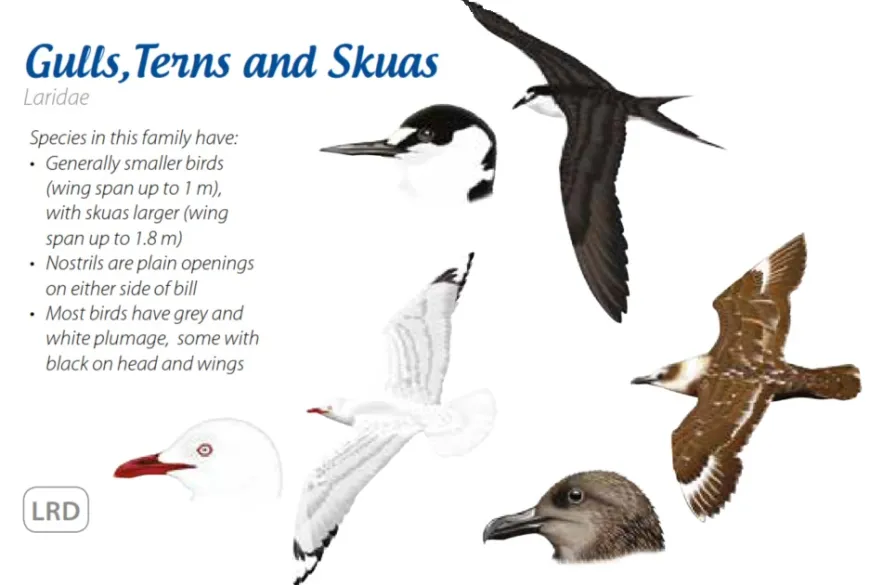

Gulls, Terns and Skuas

Latest assessment | 2020 IUCN Red List review; regional observations |

Status | Least Concern (most species). Gulls, terns, and skuas are generally not threatened in the WCPO region, and none are considered at high risk from tuna fisheries. The common species (e.g., Sooty Tern, Crested Tern, South Polar Skua) have large, globally stable populations and are classified as Least Concern by IUCN. There are a few rare or localized species in the broader Pacific (such as the endangered Chinese Crested Tern), but those do not significantly overlap with WCPFC fisheries. Overall, these groups have not experienced notable declines linked to fishing activity. |

Key findings | Unlike albatrosses or petrels, most gulls, terns, and skuas in the Pacific spend little time in the open-ocean areas where industrial tuna fishing occurs. Gulls and terns tend to stick to coastal waters, islands, and reef ecosystems. Skuas (and jaegers) are long-distance migrants but usually migrate over open ocean without frequently feeding in pelagic zones. Because of this ecology, interactions between these birds and WCPFC-managed fisheries are extremely rare – indeed, WCPFC observer programs have recorded virtually no bycatch of gulls, terns, or skuas. These groups primarily feed on live prey (fish, squid, etc.) and are not known to scavenge from longline baits or purse seine nets to any significant extent. Thus, current tuna fishing operations pose minimal risk to them. |

Management | WCPFC does not have species-specific measures for gulls, terns, or skuas, given their negligible interaction with the fishery. The general seabird conservation provisions apply if needed – for example, if a skua were caught (hypothetically), it must be released alive and reported. However, such events are practically unheard of in the WCPO. In high-risk seabird areas (temperate waters), the mitigation used for albatrosses and petrels (tori lines, etc.) would also deter any gulls or skuas present. In tropical waters, where terns are common around FADs and islands, WCPFC’s encouragement of voluntary mitigation (per CMM 2018-03) is considered sufficient given the lack of observed bycatch. In short, no additional management actions have been deemed necessary for these birds so far, beyond ongoing monitoring and adherence to the overall obligation to minimize bycatch of non-target species. |

Occurrence and risk

- Most gulls (Larus spp.) are coastal feeders and are rarely seen far from land in the WCPO. For example, the Black-tailed Gull and Slaty-backed Gull are common in East Asian coastal waters but do not venture into the central Pacific. Terns (such as Sooty Terns, Noddy terns, and various tropical species) do forage at sea but usually in association with land (breeding colonies on islands) or with surface-schooling tuna. They feed on small fish driven up by tuna schools, a very different scenario than chasing bait on a longline hook. These feeding frenzies often occur around drifting objects or FADs, where purse seiners operate, but the birds are adept at staying above the net and are seldom caught. Skuas and jaegers (Pomarine Skua, Long-tailed Jaeger, etc.) migrate through the Pacific and are occasionally seen harassing terns or boobies for food. They are “piratical” feeders but not known to take longline baits. In fact, skuas crossing the tropics are usually on migration and not actively feeding. Observer data corroborate that these birds have an extremely low overlap with fishing gear: in Pacific Island longline fisheries, no skuas and only an exceedingly few terns have ever been noted caught. This indicates that their at-sea distribution and behavior keep them largely out of trouble with regard to tuna fishing.

- Another factor is the geographic separation of fishing effort and these birds’ core habitats. Tuna longlining is most intense in the open ocean between roughly 10°N and 20°S and again in bands around 30°–40° in both hemispheres. Gulls are virtually absent from the equatorial belt (there are no “pelagic gull” species regularly there), and in the southern 30°–40°S band, the seabird fauna is dominated by albatrosses and petrels, not gulls. Sooty Terns and other tropical terns do live in equatorial waters, but they feed on live prey at the surface and are not attracted to fishing vessels in the way that albatrosses/petrels are. Skuas from the south (e.g., South Polar Skuas) migrate into the North Pacific and vice versa, but during migration they spend a lot of time resting on the water or flying – their feeding is minimal, and they don’t particularly seek out fishing boats. The bottom line is that by sheer luck of distribution, the main tuna fisheries and the main concentrations of gulls/terns/skuas don’t coincide in a hazardous way. This fortunate situation is reflected in the lack of bycatch records over decades of monitoring.

- It’s worth noting that while tuna fisheries aren’t impacting these birds, other human activities sometimes do – for example, egg harvesting and introduced predators can threaten tern colonies, and plastic pollution is a growing issue (many terns and gulls ingest plastic). However, those impacts are outside WCPFC’s mandate. From the WCPFC perspective, gulls, terns, and skuas currently require no special intervention simply because they don’t significantly interact with the fisheries under our management. They remain an important part of the Pacific ecosystem, of course, and WCPFC’s ecosystem approach means we keep a watch on all such components. If any unusual incidents (say, a gull entangled in a longline, or a tern flock diving on baits) were reported, they would be examined carefully. To date, no such pattern has emerged, confirming that these birds are at minimal risk from WCPO tuna fishing operations.

Mitigation and policy

- General mitigation measures: The seabird bycatch measures WCPFC has in place (like tori lines, night setting, etc.) were designed with albatrosses and petrels in mind, but they also incidentally protect any gulls, terns, or skuas that might be around. For example, if a vessel uses a tori line in the North Pacific (as required), that line will also deter any Black-tailed Gulls or Arctic Terns in the area from approaching the hooks. In the unlikely scenario that flocks of terns start following vessels (perhaps around drifting FADs), the crew could apply the same strategies – such as deploying scare lines or waiting for night – to avoid catching them. Because these birds are agile and mostly day-active, simply setting gear at night (standard practice in swordfish longlining) effectively eliminates their interaction. In essence, the existing toolset is perfectly adequate for preventing bycatch of gulls, terns, and skuas, to the point that no additional specialized tools have been deemed necessary.

- Legal and reporting framework: All WCPFC members are obligated by the Convention (Article 5) to minimize catch of non-target species and protect biodiversity. This overarching duty extends to even those species that aren’t covered by specific CMM provisions. Therefore, if gulls, terns, or skuas were to start interacting with a fishery, members would be expected to take action under that general obligation. In practical terms, any interaction must be recorded by observers and reported annually. The Commission’s Annual Report Part 1 includes a section for reporting seabird catches by species (or species group) – so far, reports show zero or near-zero entries for gulls/terns/skuas, indicating how seldom they feature. Nonetheless, this reporting requirement ensures transparency; were a problem to arise, it would be visible in the data. The requirement to release any captured seabird alive, mentioned in WCPFC guidelines, applies equally to these birds, though in reality fishermen rarely if ever find themselves needing to free a gull or tern from a hook in WCPO fisheries.

- Continued monitoring: Even though gulls, terns, and skuas are “off the radar” in terms of bycatch, monitoring efforts continue to include them by default. WCPFC’s regional observer program collects data on all seabird interactions, so observers are briefed that if they ever see a gull or tern caught, it should be noted and photographed for ID. This hasn’t really occurred, which is reassuring. Outside the fisheries arena, many WCPFC members engage in conservation of these birds through other agreements or national programs – for instance, countries protect important breeding sites for terns and conduct surveys of migrating skuas. By maintaining links between these broader conservation efforts and fisheries management, WCPFC ensures that any emerging issue can be caught early. Should climate or ecosystem changes alter the behavior of these species (for example, some evidence suggests certain tropical tern species might venture farther offshore as ocean climates shift), WCPFC can respond by adjusting mitigation advice. In summary, while gulls, terns, and skuas currently require little direct intervention from WCPFC, the Commission remains committed to the principle of vigilance, ensuring that all seabird species, common or rare, are safeguarded as part of the WCPO’s marine biodiversity.

Source documents: IUCN Red List (2020); SPC/WCPFC Pacific seabird study (2006) findings; WCPFC fishery data (observer records and reports).

How WCPFC manages seabird bycatch

- Mandatory bycatch mitigation in risk areas: WCPFC requires longline vessels to implement seabird mitigation measures in delineated high-risk zones. Specifically, vessels fishing north of 23°N or south of 30°S must employ mitigation such as bird-scaring lines (tori lines), weighted branch lines, and/or night setting during every set. In some mid-latitude areas (20°S–30°S), at least one measure is required. These rules target the zones where albatross and petrel interactions are known to be frequent, ensuring that mitigation is focused where it’s most needed.

- Multiple measures for effectiveness: The WCPFC seabird measure emphasizes using combinations of deterrents rather than a single solution. By deploying a mix of methods – for example, tori lines together with proper line weighting and, when possible, setting at night – vessels create redundant layers of protection. This significantly lowers the chances that a bird can access a baited hook. The Commission’s guidelines (drawing on ACAP’s best practices) detail how to properly configure each measure (e.g., tori line lengths, streamer placement, weight intervals) to maximize their efficacy.

- Safe handling and release: Though prevention is the priority, WCPFC also mandates that if a seabird is caught alive on a hook or entangled, it must be released in a manner that maximizes its chance of survival. Crew should be equipped and trained to gently retrieve birds (using a dip net for a swimming bird, for instance) and remove hooks or line from the bird without causing further injury (often using line cutters and pliers). Any live bird (even if waterlogged or exhausted) should be given time to recover and then released away from the fishing gear. These handling protocols align with FAO guidelines and are included in WCPFC’s seabird CMM annex.

- Reporting and monitoring: Members of WCPFC are required to record all seabird interactions in their logbooks and report them annually. The Regional Observer Programme provides independent monitoring of seabird bycatch; observers note mitigation used and circumstances of each interaction. WCPFC’s Scientific Committee analyzes this data to assess bycatch levels and trends. To improve data quality, WCPFC is investing in electronic monitoring (cameras on vessels) which can complement human observers, especially in detecting nocturnal bycatch events or when observer coverage is low. High-quality data enable the Commission to identify problem areas and gauge the success of mitigation measures.

- Continuous improvement: The WCPFC periodically reviews its seabird measure (CMM 2018-03) to incorporate new information and technology. It works closely with ACAP and other expert bodies to update recommended best practices. For instance, if new research shows a particular hook-shielding device or a different line weighting regime is more effective, WCPFC can approve it as an alternative mitigation option. In recent years, there has been increasing attention on extending mitigation into areas previously thought low-risk (e.g., certain tropical zones) as new tracking data shows threatened species using those waters. Proposals are considered to ensure no significant gaps in coverage.

- Capacity building and compliance: Recognizing that effective implementation requires awareness and resources, WCPFC supports training workshops for crew and observers on seabird mitigation techniques. It also encourages members to make mitigation materials (like tori line kits) available to all longline vessels, including smaller vessels that may find it challenging to procure or deploy gear. Compliance is reinforced through port inspections and audits; vessels found not carrying or using the required measures can face sanctions by their flag States. Through these efforts, WCPFC strives to ensure that rules on paper translate into real-world bycatch reduction.

- Collaboration with other organizations: Seabird conservation is a shared responsibility across ocean basins. WCPFC collaborates with other tuna RFMOs (IATTC, ICCAT, IOTC) and bodies like CCAMLR and ACAP to harmonize seabird bycatch mitigation efforts. By sharing research findings, observer data, and management experiences, they collectively improve strategies to protect albatrosses and petrels globally. This cooperation is vital for species that migrate through multiple regions; a consistent blanket of protective measures across their range vastly improves their survival chances.

Key measure: CMM 2018-03 (Conservation and Management Measure to Mitigate the Impact of Fishing on Seabirds, adopted 2018) provides the regulatory framework for these actions, updating earlier measures in line with ACAP best practices.

Data needs and next steps

- Improved monitoring coverage: A top priority is to increase the observer coverage on longline vessels, especially in fleets and areas currently under-sampled. Seabird bycatch events are relatively rare per vessel, so low coverage can miss incidents. Moving toward higher coverage (e.g., 20% or more in all relevant fisheries) and integrating electronic monitoring will provide a clearer picture of true bycatch rates. This is particularly important in the Pacific Islands’ distant-water fleets and in the equatorial regions that may not have been monitored closely for seabird interactions in the past.

- Mitigation in currently exempt areas: Ongoing analysis of seabird distribution has indicated that some threatened petrels and shearwaters range into tropical areas that were historically considered low-risk and thus exempted from mitigation requirements. WCPFC is examining whether to extend some mitigation measures to these lower-risk areas as a precaution. Trials are underway to test lightweight tori lines and other measures suitable for smaller vessels often operating in tropical waters, ensuring that any new rules are both effective and practical.

- Evaluation of mitigation efficacy: Continued scientific studies are needed to evaluate how well the existing measures are performing. This includes analyzing hook-timer or CCTV data to see how often birds attempt to take baits and are successfully deterred, and identifying any persistent loopholes (for example, if birds learn to exploit gaps in streamer lines or un-weighted sections of line). Results will guide refinements like improved tori line designs or adjusted weight placements to close those gaps.

- Post-release survival research: For the few seabirds that are caught alive and released, it’s largely unknown how well they survive afterward. Tagging released albatrosses or petrels with satellite or archival tags (in non-invasive ways) could provide insight into their fate. If survival is low, even with careful release, it underscores even more the need to prevent captures outright; if survival is high, it validates the current handling guidelines and could identify ways to further improve them (for instance, rehabilitation techniques for exhausted birds).

- Integration of climate change scenarios: As ocean conditions change, seabird foraging ranges and migration timings may shift, potentially bringing species into contact with fisheries in new ways. The Scientific Committee is incorporating climate models and seabird ecological studies to predict future overlap hotspots. Anticipating these shifts will allow WCPFC to proactively adapt management measures (like seasonal or spatial extensions of mitigation) to emerging risk areas rather than reacting after bycatch increases. Ensuring the flexibility and responsiveness of seabird bycatch measures in the face of climate change will be an ongoing task.