🐬 WCPFC Cetacean Bycatch Mitigation Terms

This guide explains key practices and concepts used by the WCPFC to reduce whale and dolphin (cetacean) bycatch and interactions. These terms appear in conservation measures and safe handling guidelines for marine mammals in tuna fisheries.

📘 Definitions and Measures

Depredation: When cetaceans remove or eat fish from fishing gear (e.g., tuna caught on longlines). Depredation often leads to whales or dolphins getting hooked or entangled while trying to take bait or catch. It is a major cause of marine mammal interactions in longline fisheries, especially with species like false killer whales that target tuna on the lines.

Acoustic Pingers: Small sound-emitting devices that can be attached to fishing gear (typically nets) to deter cetaceans. Pingers create regular noise signals underwater, which in some fisheries help keep dolphins and porpoises away and thus reduce bycatch. Though not yet widely used in WCPO tuna fisheries, pingers are a potential mitigation tool being researched for longlines to discourage species like pilot whales from approaching baited hooks.

Purse Seine Backdown: A safe-release procedure originally developed in the Eastern Pacific tuna fishery to free dolphins accidentally encircled in purse seine nets. In a backdown maneuver, the vessel slows and reverses after encircling a school, creating an opening in the net (often aided by a special net panel) through which trapped dolphins can escape. WCPFC vessels generally avoid setting on dolphins, so backdown is not routine in the WCPO, but the principle of slowing or opening the net to let cetaceans out is part of recommended best practices if a dolphin or small whale is encircled.

Non-entangling FAD: As defined in turtle bycatch context, a Fish Aggregating Device designed to prevent entanglement of marine life. Non-entangling FADs lack any open netting or loose ropes in which animals can get snared. This protects not only turtles and sharks but also cetaceans – for example, preventing dolphins from getting their rostrum or flippers caught in old webbing under FADs. WCPFC encourages fleets to deploy non-entangling FADs to eliminate entanglement incidents.

Safe Release Guidelines: Protocols adopted (or recommended) by WCPFC to ensure that any cetacean caught or entangled is handled in a way that maximizes its chance of survival. These guidelines include stopping fishing operations to attend to the animal, using proper equipment (line cutters, de-hookers) to free it without causing further injury, and crew training on techniques like supporting an animal’s weight if lifted, or reviving exhausted animals. Safe release guidelines are based on internationally recognized best practices (e.g., FAO and IWC advice) and are continuously refined as new information becomes available.

Cetaceans in the WCPO

This page summarizes the status of certain whale and dolphin species in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean (WCPO) and the bycatch mitigation actions adopted by the WCPFC. Dozens of cetacean species occur in the WCPFC area (at least 34 species have been recorded), ranging from large whales to small dolphins. Among these, five toothed whale/dolphin species (false killer whale, short-finned pilot whale, rough-toothed dolphin, bottlenose dolphin, and spinner dolphin) are the most frequently involved in interactions with WCPO tuna fisheries. All cetaceans are protected under international agreements and many have vulnerable or threatened populations. Incidental capture or entanglement in longline and purse seine gear is identified as a significant threat to these marine mammals, given their slow reproduction and social nature. Even a single mortality can be significant for local populations.

WCPFC addresses cetacean bycatch through operational regulations, crew training, and reporting requirements. Purse seine vessels are prohibited from deliberately setting nets around any cetaceans, and if a whale or dolphin is unintentionally encircled, the crew must cease hauling and release the animal alive following established safe-handling guidelines.

Longline vessels are similarly required to promptly release any cetacean caught on their lines and are banned from retaining any cetacean parts or carcasses. Although no specific gear modifications (such as hook changes or acoustic devices) are mandated yet for cetaceans, captains and crews are expected to use all reasonable measures to avoid interactions (for instance, steering away from pods sighted ahead) and to minimize harm if an interaction occurs.

All interactions must be recorded – observers and fishermen log each incident with details on species, number, and condition upon release. By implementing these measures – in concert with national marine mammal protection laws of member countries – the WCPFC aims to minimize cetacean mortality in tuna fisheries and contribute to the long-term conservation of whale and dolphin populations in the Pacific.

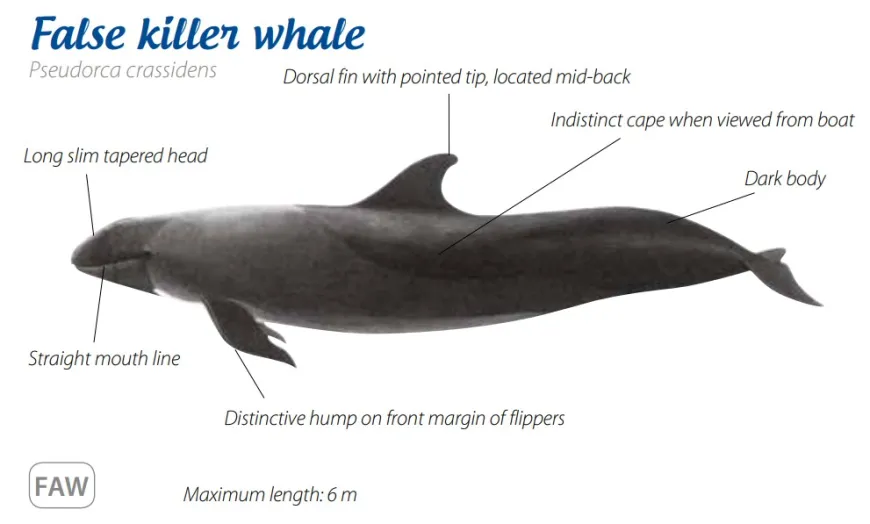

False Killer Whale (Pseudorca crassidens)

Latest assessment | 2021 Pacific Islands regional review & 2018 IUCN status update |

Status | Near Threatened globally. Some local populations (e.g. around main Hawaiian Islands) are Endangered or declining. |

Key findings | False killer whales are large oceanic dolphins that roam tropical and subtropical waters worldwide. In the WCPO they occur both offshore and near islands, living in social groups that hunt fish and squid. They are long-lived (up to ~60 years) and have low reproductive rates (calving intervals ~6–7 years), making them vulnerable to even low levels of adult mortality. Studies indicate that false killer whale groups in parts of the Pacific have suffered declines due to human impacts – for example, the insular population around Hawaii is estimated to have shrunk significantly in recent decades, likely due in part to fishery bycatch and historical culling. False killer whales are notorious for interacting with longline fisheries: they are attracted to bait and caught fish (depredation), which often leads to individuals being hooked or entangled in the gear. This species accounted for the highest number of reported cetacean interactions in WCPO observer data:contentReference[oaicite:3]{index=3}. Because of their social nature, multiple whales may engage with a fishing vessel at once, raising the risk of several getting caught in a single event. |

Management | WCPFC’s conservation measures for cetaceans (e.g. CMM 2011-03) directly address false killer whale bycatch. Purse seine vessels must not set nets around these whales intentionally, and any false killer whale encircled accidentally must be released alive following the mandated safe-release steps (stop net roll, gently loosen net, etc.). For longline fisheries, although no gear changes are yet required, there is a strict prohibition on keeping false killer whales (dead or alive) – any hooked animal must be released, and fishers are expected to do so in a manner causing the least harm (e.g. cutting the line as close to the hook as safely possible). The WCPFC Scientific Committee has highlighted false killer whales as a priority “species of concern” for bycatch mitigation, given their high interaction rate and small population units. Additional national measures reinforce their protection: for instance, the United States requires its Hawaii-based longline fleet to implement a Take Reduction Plan, which includes strategies like area closures when bycatch thresholds are exceeded and guidelines against lethal responses to depredation. While WCPFC has not adopted specific acoustic deterrents or hook modifications for false killer whales yet, it encourages research into such mitigation. Observer programs and (increasingly) electronic monitoring are crucial for documenting false killer whale interactions, and WCPFC members must report all incidents in annual reports, ensuring that mortality or injury of this species is closely tracked. |

Range and fishery interactions

- False killer whales range widely across the Pacific, from equatorial waters to subtropical regions. They often frequent the high seas as well as the waters around Pacific islands. Notably, they can form long-term resident groups around island chains (e.g., Hawaii, French Polynesia) as well as roam in pelagic waters. This extensive range means they overlap considerably with tuna fisheries. They are adept at taking fish off both longline hooks and occasionally from purse seine catches, which is why interactions occur in both gear types. Longline depredation events (where they remove tuna from hooks) are commonly reported; in many cases the whale may get hooked in the mouth or become entangled in the branchline while attempting to eat the catch. Purse seine interactions are less frequent but can happen if false killer whales chase the same prey as tunas – occasionally they may be unintentionally encircled when feeding in proximity to a tuna school being netted.

- Because of their size (up to 5–6 m) and strength, false killer whales caught on lines can break gear or escape, sometimes with hooks or line still attached, which may lead to unobserved mortality later. Fishers historically sometimes resorted to harmful methods (such as shooting or using explosives) to deter them from depredating catches; however, such actions are illegal under most jurisdictions now and are strictly prohibited by WCPFC. Instead, vessel operators are encouraged to avoid areas where false killer whales are repeatedly encountered – for example, if a longline vessel experiences depredation by a group of false killer whales at a certain location or time, the recommended practice is to move fishing grounds to prevent continued interactions. Some fleets have adopted this move-on strategy voluntarily when depredation becomes problematic.

- Interactions with false killer whales have a high likelihood of serious injury or death for the animals if not managed carefully. A hooked false killer whale that is brought close to a vessel can thrash violently, risking injury to itself and crew; thus, WCPFC guidelines advise cutting the line before the animal is too near the boat, unless it can be calmly led to the side and de-hooked without stress. In purse seine scenarios, if one or more false killer whales are discovered inside a closing net, the crew should refrain from pursing the net further; often the best approach is to release tension and even lower a part of the net to allow the whale(s) to escape. Crew should never attempt to haul a large whale onto the deck. Instead, all efforts focus on letting the animal free itself or guiding it out with minimal contact.

Effective bycatch mitigation for fleets

- Use caution and proactive avoidance: If false killer whales are seen or begin following a vessel, longline crews can try tactics such as delaying setting gear until the animals leave, or hauling gear earlier/faster if whales show up during retrieval (to reduce the window for depredation). Some vessels deploy acoustic decoys or noise-makers in an experimental effort to distract or deter them, though consistent success has not been proven. The most effective measure so far is spatial avoidance – i.e., moving away from locations where false killer whales are actively depredating.

- Gentle handling and release: It is essential that crew be trained in safe handling because false killer whales are powerful and usually larger than crew members. Longliners should have long-handled cutters to sever branch lines under tension (this avoids getting too close to a struggling whale). If a false killer whale is hooked but calm at the surface, crew can use a long pole with a sharp blade or a bolt-cutter to cut the hook or line as near the mouth as feasible, thereby removing as much gear as possible. They should never use gaffs or sharp implements on the body. For purse seiners, if a whale is in the net, crew might use a small boat (work skiff) to gently lead the animal toward an opening. Keeping noise and commotion down will avoid agitating the whale further. All releases should be performed as quickly as possible but without panic, aiming to let the animal return to the open sea in the best condition.

- No retaliation policy: Crew must understand that under WCPFC regulations and national laws, harming or killing a cetacean intentionally (even if it has taken catch) is not allowed. Instead of retaliation, fleets are encouraged to invest in non-lethal deterrents. For example, some longline vessels have tried using “weak hooks” that straighten under the pull of a very large animal – these can sometimes allow a hooked whale to free itself (at the cost of losing some fish). While gear tweaks like this are still being tested, a culture of protection is key: the crew’s priority should be the safe release of the animal, even if it means sacrificing some catch or gear.

Monitoring priorities

- Improve data collection on interactions: Given that false killer whale interactions are relatively infrequent events spread over a huge ocean, higher observer coverage on longliners (currently only ~5%) is needed to accurately estimate bycatch rates. Expanding electronic monitoring (cameras) on longline vessels can help capture depredation and hooking events that otherwise go unrecorded. Additionally, fishers should be encouraged to report depredation even when whales do not get hooked, as frequent non-catch interactions might signal areas of concern.

- Post-release outcome studies: It is not well known how successfully false killer whales survive after release, especially if they swim off with a hook or trailing line. Tagging individuals that have been caught and released (with satellite or radio tags) could provide data on their survival and movements post-interaction. Research programs could collaborate with fishermen to opportunistically tag any false killer whale that is freed in relatively good condition. Information on survival rates will inform how effective current release practices are and whether additional measures (e.g. better hook removal techniques) are needed.

- Identification of population structure: Collecting tissue samples from false killer whales (for genetic analysis) or high-quality photos (for photo-ID catalogs) during interactions can help determine which population an individual belongs to. For instance, genetic tests can show if a whale caught in the high seas is related to a specific archipelago’s population. This matters because some populations are much smaller and at greater risk – if a certain population is suffering disproportionate bycatch, targeted mitigation (like time/area closures in that population’s core habitat) could be considered. Collaborative work with organizations like SPREP and national research agencies can facilitate these data collections.

Source documents: WCPFC Cetacean CMM 2011-03 (and 2019–2023 proposed amendments); SPC/WCPFC Observer data analyses (2013–2020) highlighting false killer whale interactions:contentReference[oaicite:4]{index=4}; NOAA Fisheries reports on the Hawaiʻi false killer whale stock; IUCN Red List (2018) classification.

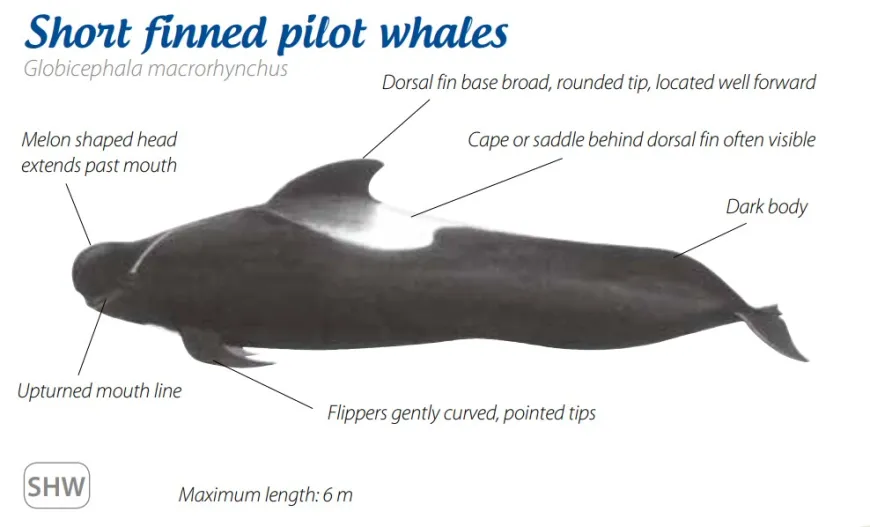

Short-finned Pilot Whale (Globicephala macrorhynchus)

Latest assessment | No Pacific-wide abundance assessment; IUCN Red List 2018 (global) |

Status | Least Concern globally. Widespread and locally common, though precise population trends are uncertain. |

Key findings | Short-finned pilot whales are medium-sized toothed whales (5–7 m in length) found throughout tropical and subtropical oceans. In the WCPO they are frequently observed in deep offshore waters as well as around island slopes. Highly social, they travel in pods that can range from a dozen to over 50 individuals, often with strong family bonds. There is no evidence of major global decline, and the species is still considered abundant, but pilot whales’ slow reproduction (maturing at ~10 years, calving every 5–8 years) means populations could be impacted by sustained losses. In the past, some coastal communities (and whaling operations) in the Pacific took pilot whales for meat, but today large-scale hunting is minimal in this region. The primary threat in the WCPO is incidental bycatch. Pilot whales have been documented interacting with both purse seine and longline fisheries: they sometimes feed on the same prey as tuna. Observers have reported pilot whales being encircled in purse seine nets (likely when they are near a tuna school at the surface), as well as individuals hooked or entangled in longlines (occasionally when they take bait or become snagged while investigating gear). Though pilot whales did not historically face the targeted dolphin fishing that occurred in the Eastern Pacific, they nonetheless appear in bycatch records and are among the more commonly recorded cetaceans in WCPO tuna fisheries:contentReference[oaicite:5]{index=5}. |

Management | Under WCPFC measures, short-finned pilot whales benefit from the same protections afforded to all cetaceans. Purse seiners are forbidden from intentionally setting on pods of pilot whales, and if a pilot whale is inadvertently encircled, it must be released following the protocols (stop hauling, avoid entangling the whale in net meshes, etc.). Longline vessels are required to release any incidentally caught pilot whale and are not permitted to retain them. There are currently no gear requirements specific to pilot whales (such as hook type or deterrent devices) mandated by WCPFC. However, many of the general bycatch mitigation guidelines apply: for example, vessels are encouraged to avoid fishing in areas when large groups of pilot whales are sighted and to be vigilant during hauling to quickly release any animals that may be hooked. Data reporting is also crucial – interactions with pilot whales must be recorded by observers or in logbooks. Some member nations have additional provisions: the US fleet, for instance, treats pilot whales as protected species under domestic law (Marine Mammal Protection Act), which entails crew training in safe handling and periodic review of bycatch mitigation efficacy. At the regional level, WCPFC’s Scientific Committee has noted the need to monitor pilot whale bycatch and improve identification (to distinguish them from other similar “blackfish” dolphins). In summary, pilot whales are managed through the general cetacean bycatch framework, emphasizing no deliberate harm and best possible release practices, alongside efforts to improve observation and data on their interactions with fisheries. |

Range and interactions

- In the WCPO, short-finned pilot whales inhabit warm waters from about 30°N to 30°S, often along thermal fronts and areas of high productivity. They are deep divers, feeding on squid and fish, and will also take surface schooling fish when available. Pilot whales can often be found in proximity to tuna schools – not because they prey on tuna, but because they and tuna may both target the same bait fish (such as sauries or mackerel). This co-occurrence sometimes leads to pilot whales being mixed in with tuna schools that are targeted by purse seiners. If a purse seine net is deployed on such a school, any pilot whales present risk being encircled as well. Their strong social cohesion means if one or a few are in a net, others from the pod might stay nearby, potentially complicating release efforts.

- Longline interactions with pilot whales typically stem from depredation on bait or catch. A pilot whale that grabs a fish from a hook can get the hook lodged in its mouth or become entangled in the line. Given their size and power, they may be able to break free on their own, but they can also drown if they are entangled and cannot surface. Some pilot whales carry scars (such as dorsal fin disfigurements or line cuts) that are indicative of past encounters with fishing gear, suggesting that not all interactions are observed or reported. The true level of pilot whale bycatch may thus be higher than documented, especially in the longline sector where observer coverage is low.

- Unlike some dolphin species, pilot whales do not typically bow-ride or closely approach moving vessels for long periods, but they have been observed milling around fishing operations, possibly drawn by offal or the commotion of hauling. Fishers occasionally report that pilot whales, much like false killer whales, can learn to follow longline vessels to snatch catches – although this behavior is less documented for pilot whales than for false killer whales. Nonetheless, when it does occur, it presents safety issues and economic loss, reinforcing the need for preventive measures (like avoiding known aggregation areas or times when pilot whales are common).

Effective actions for fleets

- Avoid encirclement: Purse seine captains should be trained to spot the signs of pilot whales in the vicinity of tuna schools (e.g., sightings of black dorsal fins or the whales’ surfacing patterns). If pilot whales are observed near a potential set, the set should be postponed or relocated. Many skippers will already choose free-swimming tuna schools without marine mammals, since mixing with large mammals can make the set riskier and may also indicate the tuna are dispersed. During net setting, crew in crow’s nests or on punts can keep watch – if a pilot whale is seen inside the net early, one technique is to deploy a small boat to gently herd it out before the net closes completely.

- Safe release techniques: If a pilot whale is captured in a net or on a line, releasing it with minimal injury is the goal. For purse seine, once the whale is noticed, the vessel should go into backdown maneuvers or otherwise create slack. In some cases, cutting part of the net (sacrificing a section) has been done to free large cetaceans; this is costly but may be necessary if a whale is hopelessly entangled. For longline vessels, having a “cetacean release kit” is useful – this might include a long pole with a knife to cut branch lines from a distance, and bolt cutters capable of cutting hooks. If a hooked pilot whale is alongside, the crew might be able to remove the hook with a long-handled de-hooker if it’s shallow, but if not, they should cut the line as close as possible to the mouth. Importantly, all such efforts should prioritize crew safety as well – a thrashing 2-ton pilot whale is dangerous, so release should be attempted only when the animal is calm enough and people are positioned safely.

- Experimental mitigation: Researchers are investigating methods to reduce pilot whale interactions. One idea is acoustic deterrents – devices that emit specific noises unpleasant to pilot whales in hopes of keeping them away from fishing gear. Another concept is “alternative prey” release – dropping bits of fish off the opposite side of a longline vessel to distract pilot whales away from the line hauling area (this has been tried informally by some crews). While none of these methods are formally adopted yet, cooperative trials could be encouraged. Fleet communication is also key: if one vessel experiences a lot of pilot whale depredation in an area, alerting other vessels can help them decide to temporarily avoid that hotspot. Such voluntary fleet-wide moves have precedent in other fisheries (e.g., to avoid bycatch hotspots).

Monitoring and research

- Species identification and data accuracy: Observers and crew should be trained to distinguish short-finned pilot whales from other similar cetaceans (like false killer whales or melon-headed whales). Misidentification can occur, especially at a distance. Improved identification (through training and use of identification cards) will ensure the data on “pilot whale” interactions is reliable. WCPFC is working on refining observer data collection so that species like pilot whales are properly recorded rather than grouped into generic categories (e.g., “blackfish”).

- Abundance and distribution studies: There is a need for more surveys to estimate pilot whale populations in the WCPO. Line-transect surveys, acoustic monitoring, and even citizen science (e.g., whale watching logs) can contribute to understanding where pilot whales are most numerous. Knowing their core areas or migratory patterns can help in assessing overlap with fisheries. For example, if certain seamount areas or months of the year show high pilot whale presence, managers could consider advisory notices to fishers or even temporal/spatial management if bycatch becomes a serious concern.

- Post-interaction outcomes: Similar to other cetaceans, the fate of pilot whales after release is not well documented. Tagging a few individuals that survive fishery interactions (with minimally invasive satellite tags) could shed light on their survival and behavior afterwards. In addition, collecting biological samples from any dead pilot whale (e.g., one that might be found floating after an interaction) is valuable – samples can reveal diet (to see if they had been eating bait or target species), contaminant levels, or genetics. These data feed into broader understanding of pilot whale health and the population impact of bycatch.

Source documents: WCPFC Cetacean Measure (2011-03) applying to pilot whales; Pacific scientific studies (Oleson et al. 2019 on Marianas pilot whales; Hill et al. 2018) on distribution and interaction; IUCN Red List (Globicephala macrorhynchus, 2018).

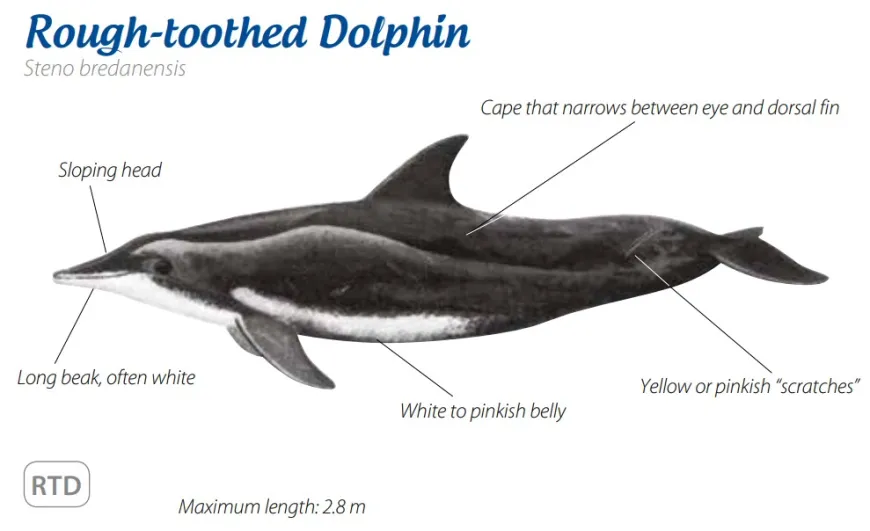

Rough-toothed Dolphin (Steno bredanensis)

Latest assessment | No WCPO-specific survey; IUCN Red List 2018 (global) |

Status | Least Concern globally. Data on Pacific sub-populations are very limited. |

Key findings | Rough-toothed dolphins are a medium-sized dolphin species (~2.5 m long) named for the ridged texture of their teeth. They prefer deep tropical and subtropical waters and are often found around islands, seamounts, or in open-ocean settings where prey is abundant. Unlike many dolphins, they don’t have a clear separation between the melon and beak, giving their head a distinctive conical shape. In the Pacific Islands region, there is scant population information – rough-toothed dolphins are observed in various locales (from Polynesia to Micronesia), but no comprehensive estimate exists of their numbers. They are not currently considered endangered, but as a top predator that sits relatively high in the food chain, they face threats from pollution (like bioaccumulation of toxins) and fisheries interactions. Observers have recorded rough-toothed dolphins incidentally caught in purse seines and on longlines, though in smaller numbers compared to some larger odontocetes. This species’ tendency to associate with floating objects and debris (perhaps to hunt the small fish congregating there) can put them at risk of entanglement in FADs or nets. For instance, some stranded rough-toothed dolphins have been found with net marks or fragments, indicating entanglement. Also, researchers have noted that rough-toothed dolphins in parts of the Pacific show scars and injuries that could be from interactions with fishing gear:contentReference[oaicite:6]{index=6}. In summary, while not as frequently caught as false killer whales or pilot whales, rough-toothed dolphins do interact with WCPO fisheries and any mortality could be significant given the unknown size of their populations. |

Management | WCPFC’s general cetacean bycatch measures cover rough-toothed dolphins. Purse seine crews must avoid setting on them intentionally, and if a rough-toothed dolphin is spotted in the net, operations must pause to facilitate its safe release. Because these dolphins are smaller and more agile, they can often escape an opened net if given the opportunity – hence, skippers are instructed to lower the net or roll a portion back if a dolphin is trapped. For longline vessels, any hooked rough-toothed dolphin must be released immediately; since they are relatively small, crew might attempt to bring a calm individual alongside in a brail or net to remove the hook, but only if this can be done without harm. Otherwise, the line is cut as close to the animal as possible. There are no species-specific WCPFC rules (e.g., no quotas or time-area closures) for rough-toothed dolphins, largely due to insufficient data on interaction rates. However, the push for non-entangling FADs directly benefits this species by reducing the chance of them getting ensnared in FAD tethering materials or old netting. Additionally, many member nations have domestic protections for all dolphin species – for example, several Pacific Island countries prohibit harassment or catching of dolphins in their waters – which complements WCPFC’s measures on the high seas. Continued observer reporting and upcoming electronic monitoring will help determine if stronger measures for rough-toothed dolphins (like specific handling guidelines or mitigation devices) might be required in the future. |

Interactions and risk

- Rough-toothed dolphins tend to forage in small groups (often 10–20 individuals) and are known to have a varied diet of fish, squid, and octopus. In the WCPO, they are frequently noted around fringe areas of tuna fishing grounds. They can sometimes be curious about boats – reports exist of rough-toothed dolphins approaching slow-moving vessels or riding bow waves, though they are less exuberant in this behavior than some other dolphins. This curiosity, combined with attraction to fishing debris, may explain why they sometimes end up inside purse seine nets or near longline bait. A net set on a school of tuna that happens to be near drifting debris could inadvertently catch rough-toothed dolphins if they are foraging there. Similarly, they might investigate longline floats or bait, increasing bycatch risk.

- Entanglement in floating ropes or nets is a particular hazard for this species. Prior to WCPFC’s ban on entangling FAD designs, rough-toothed dolphins (like other wildlife) could become ensnared in the webbing that used to hang beneath FADs. Such entanglements might go unobserved if they occur far from vessels – a dolphin could drown and eventually wash ashore with netting still on it. With non-entangling FADs now promoted, this risk is expected to decline. Nonetheless, any discarded fishing gear (ghost nets) poses a similar threat, and rough-toothed dolphins, often being offshore, are among the species that can get caught.

- Longline bycatch of rough-toothed dolphins, while infrequent, has been reported. Typically, a dolphin might be found hooked in the mouth, still alive, when the gear is hauled. Their relatively smaller size (compared to pilot whales or false killer whales) means if they are alive, they can sometimes be lifted carefully for hook removal – some crews have successfully disentangled rough-toothed dolphins by using a stretcher or canvas to support the animal’s weight while extracting gear, then sliding it back into the sea. However, this is only feasible in ideal conditions and when the animal is docile; more often, cutting the line is the only safe option.

Effective actions

- FAD management: Ensuring that all deployed FADs are non-entangling and, preferably, made of biodegradable materials helps protect rough-toothed dolphins. Crew should routinely inspect any FADs they service or encounter for entangled animals. If a live dolphin is found tangled in FAD lines, the priority is to free it by cutting away lines (taking care to avoid causing deep cuts to the animal). Ideally, this is done with the animal alongside the vessel in the water – using a long pole with a knife or a boat hook to snag and sever the offending ropes. The crew should never simply cut a FAD loose to “let the animal free” while still entangled, as that just creates an uncontrolled situation; instead, they should bring the entangled portion close and methodically remove wraps from the dolphin if possible. Training in such disentanglement could be included in safety drills.

- Purse seine release: When a rough-toothed dolphin is noticed in a purse seine net, it’s important to stop hauling immediately. Often these dolphins will swim deep or stay near the net edge looking for an escape. One effective method is to partially submerge a corkline (float line) at one end of the net to create an escape route – the dolphin can sense that opening and swim out. Crew can assist by gently splashing or making noise on the side of the net opposite the opening to herd the dolphin toward the exit. Using a dip net to physically scoop a rough-toothed dolphin out is generally not advised (they are too heavy and can panic); letting it find its way out on its own is less stressful. After the animal is clear, the normal fishing operation can resume.

- Longline practices: To reduce the chance of hooking rough-toothed dolphins, some skippers avoid dumping offal or spent bait while gear is soaking, since food scraps might attract dolphins to the vicinity. Additionally, if dolphins are seen during line hauling, crew might try to scare them off by various harmless means (e.g., banging on the hull, though dolphins often habituate to such sounds). While there is no universally successful deterrent, maintaining a steady retrieval (not leaving slack line where a curious dolphin could get entangled) can help. In the event one is hooked, follow the same protocol as for other small cetaceans: try to keep the animal calm, and either release it by cutting the line close to the hook or carefully de-hooking if conditions allow. Reporting the incident, including whether the dolphin swam away strongly or not, is important for assessment of these mitigation efforts.

Data and monitoring needs

- Increased reporting and species resolution: Rough-toothed dolphin bycatch might be under-reported because observers sometimes lump unidentified dolphins into broad categories. Training observers to recognize the unique features of Steno bredanensis (such as its all-white lips and spotted flanks) will improve records. Enhanced data collection (including photographs of bycaught individuals) will also help verify species IDs after the fact. The Scientific Committee has recommended more resources for observer training in marine mammal identification to address this issue.

- Biological sampling: If any rough-toothed dolphin bycatch does occur (especially if an animal dies), collecting samples (with proper permits) would greatly aid science. Genetic samples can confirm population connectivity – e.g., are the individuals caught in WCPO fisheries part of a larger pan-Pacific group or more isolated regional stocks? Also, analyzing stomach contents or tissues could reveal diet and pollutant loads, providing insight into their ecology and what risks (like heavy metal accumulation or microplastics) they face in addition to fishery interactions.

- Collaboration with other regions: Rough-toothed dolphins are found not only in the WCPO but also in the Eastern Pacific and Indian Ocean. Sharing data with other RFMOs and conservation groups can identify if similar bycatch patterns occur elsewhere. For example, if another fishery has success with a certain dolphin deterrent or handling technique, WCPFC can learn from that. Conversely, the experiences in the WCPO (though limited in number) contribute to the global understanding of this species’ interaction with fisheries. WCPFC’s Ecosystem and Bycatch Working Group can facilitate such exchanges of information and promote consistent best practices across oceans.

Source documents: WCPFC Sea Turtle & Cetacean Measures (non-entangling FAD guidelines, safe release protocols); FAO marine mammal bycatch review (global mitigation techniques); Pacific observer reports (e.g., interaction scars noted in Hill et al. 2020) on rough-toothed dolphins.

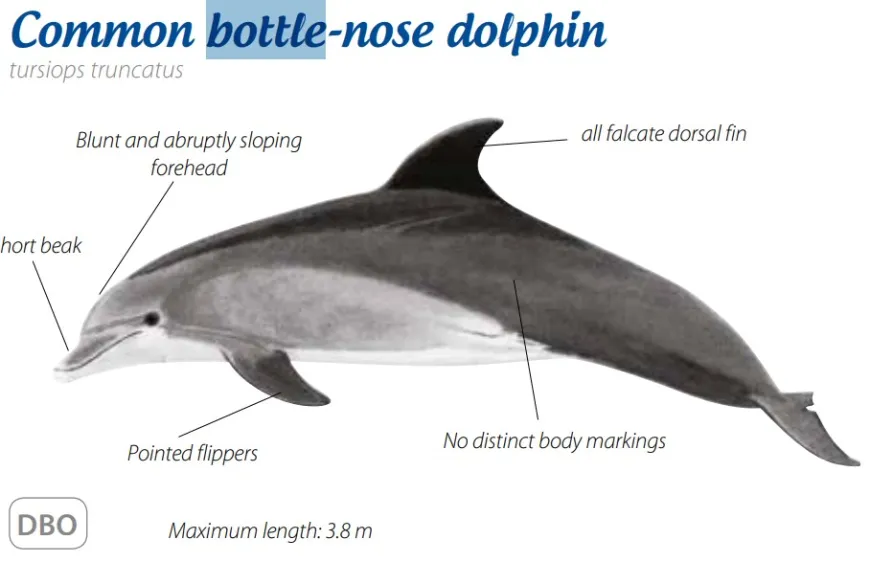

Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops spp.)

Latest assessment | Local population studies (2015–2021); IUCN Red List 2018 (species-level) |

Status | Least Concern (Common bottlenose); Near Threatened (Indo-Pacific bottlenose). Widespread, but some isolated sub-populations are small and vulnerable. |

Key findings | Bottlenose dolphins are perhaps the most well-known dolphin genus, comprising at least two species in the Pacific: the common bottlenose (Tursiops truncatus) and the Indo-Pacific bottlenose (Tursiops aduncus). Common bottlenose dolphins tend to be larger and often occupy more offshore or cool-water environments, whereas Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins are generally smaller, spotted on the belly in adulthood, and frequent coastal and shelf waters of tropical regions. In the WCPO, “Tursiops” dolphins are reported from almost all member countries’ waters – they are adaptable and opportunistic feeders, eating fish and cephalopods in diverse habitats. Overall numbers globally are high (hence their Least Concern status), but many local populations (for example, those resident in a particular lagoon or island group) can be quite limited in size (tens to low hundreds of individuals) and face pressures from human activities. In the Pacific Islands, bottlenose dolphins have been subject to directed take in a few cases (notably live-capture exports from the Solomon Islands in the 2000s, which targeted Indo-Pacific bottlenose, and some traditional drive hunts in small numbers). However, in the WCPFC context, the main concern is bycatch. Observer data shows bottlenose dolphins among the top five cetaceans interacting with purse seine fisheries:contentReference[oaicite:7]{index=7}. They are occasionally encircled in nets, perhaps when they co-occur with free-swimming tuna schools or investigate baitfish around FADs. Bottlenose dolphins are less commonly hooked in longlines (they don’t regularly depredate like false killer whales do), but there have been instances of entanglement or hooking, especially involving offshore (pelagic) bottlenose individuals. Their intelligence and strong social structure mean they may sometimes avoid dangers (for instance, they can learn to evade nets), yet any that do get caught can suffer serious consequences. Given their coastal affinity, bottlenose dolphins also face significant threats from gillnet fisheries and habitat degradation, but those are outside WCPFC’s high-seas mandate. |

Management | WCPFC conservation measures treat bottlenose dolphins like all other cetaceans in terms of bycatch mitigation – there are no special exemptions or species-specific rules. Purse seiners must refrain from setting on pods of dolphins intentionally (a practice that, unlike in the Eastern Pacific, is not a target fishing method in the WCPO anyway). Should a bottlenose dolphin be encircled, the crew is obligated to follow the safe release procedure (stop net hauling, allow the animal to be released alive). In practice, many WCPO purse seine captains will try to avoid encircling dolphins entirely, as they know doing so can damage the catch and the gear. For longliners, any caught bottlenose dolphin must be promptly released and not brought onboard (other than to free it if necessary). The prohibition on retention means fishers cannot keep dolphins even if they are found dead; this discourages any directed catching. Several WCPFC member nations have additional protections – for example, Australia and many Pacific Island states list bottlenose dolphins as fully protected within their EEZs, and the USA’s regulations require logbook reporting of any marine mammal interaction in addition to WCPFC’s requirements. To support these policies, training workshops have been conducted in some regions (often in collaboration with SPREP or NGOs) to show fishers how to identify different dolphin species and how to perform safe handling. Moving forward, the WCPFC community is watching indicators like the number of dolphin entanglements on FADs and purse seine nets; if data suggest increasing interactions with bottlenose or other dolphins, the Commission may consider strengthening measures (for instance, refining net design or increasing enforcement of dolphin-safe practices). |

Range and behavior

- Bottlenose dolphins in the WCPO display a dual habitat usage: some groups live close to shore around islands, bays, and reefs (these are often Indo-Pacific bottlenose), while others range in deeper offshore waters, including near seamounts or productive pelagic zones (likely common bottlenose). The inshore populations often have smaller home ranges and strong site fidelity – for example, a pod might reside around a single atoll for years. Offshore populations are more mobile. Both types can overlap with tuna fisheries: coastal ones might encounter purse seiners that operate near island FADs or nearshore aggregations of tuna, and offshore ones can cross paths with longline gear or free-swimming tuna schools targeted by purse seine sets.

- Bottlenose dolphins are generally robust and powerful swimmers, and they have been observed escaping purse seine nets by leaping over corklines or finding gaps – they are the same species often seen performing acrobatics, which can serve them well in evading capture. However, entanglement can still occur, especially if a net fold or loose mesh snags a fin or fluke. Within the net, their behavior can be frantic if panicked, or sometimes eerily calm (some dolphins have been seen staying near the net lead line until it’s opened). Their reactions vary, which means crews must be prepared for either scenario during a release operation.

- Longline interactions with bottlenose dolphins are rarer, but not impossible. One scenario is a dolphin getting tangled in the monofilament line itself (not necessarily hooked) – perhaps after chasing a fish that’s struggling on a hook. Offshore bottlenose dolphins have been noted following ships (including longliners) to feed on discarded bycatch; if they associate vessels with food, they might investigate fishing gear. This is still an infrequent occurrence compared to other species. Nonetheless, every few years, reports surface of a bottlenose found on a line. These tend to be large individuals, which can be challenging to release if they are brought up alive.

Effective practices for crews

- Dolphin-safe setting and detection: Although WCPO fishers don’t target dolphins, they should still employ vigilance. Using binoculars or bird radars to spot signs of life before setting a purse seine can help – for instance, if a large pod of dolphins is seen in the area, it might be wise to skip setting even if tuna are present, as mixing could occur. Some modern purse seine operations have begun using drones to look at schools before setting; a quick drone scan could confirm if dolphins are intermingling with the school. While not standard, these technologies could improve dolphin avoidance.

- Handling entangled dolphins: If a bottlenose dolphin is accidentally netted and becomes entangled in mesh, the crew’s immediate job is to support the animal to breathe. This might involve lifting part of the net slightly so the dolphin’s blowhole is at the surface. Crew should then carefully untangle the mesh by hand (wearing gloves), cutting ropes if needed. Bottlenose dolphins, being smaller than pilot whales, can sometimes be guided by hand – for example, crew might grab the dolphin’s pectoral fins or fluke to maneuver it (with extreme care not to injure or be injured). One person should lead the head while another supports the tail to keep the spine straight if lifting slightly. If the dolphin is netted in the bunt (the last part of the purse seine), releasing one end of the bunt can open enough space for it to swim out. Importantly, minimize stress: quiet voices, no sudden movements, and shade (if it’s daytime and the sun is hot) all help reduce panic and prevent further harm to the animal.

- Post-release care: Sometimes a dolphin may be sluggish or exhausted after release – for example, if it was in a net for a long time or struggled. If a dolphin is freed but not actively swimming away, crews (especially on longline vessels or smaller boats) have on occasion used a technique of “revival”: gently towing the dolphin slowly (holding it by the dorsal fin or using a stretcher under it) to force water through its blowhole and stimulate breathing, then letting it go once it starts to resist. While not always feasible, this kind of attentiveness can make the difference for a fatigued animal. Generally, however, in a purse seine context, once the net is sufficiently opened, the dolphin will usually make its own way out; ensuring it has a clear route is the best thing the crew can do.

Monitoring and collaboration

- Distinguishing species in reports: Observers often just record “bottlenose dolphin” without specifying which species (common vs. Indo-Pacific). Genetic or photographic evidence is needed to differentiate them in many cases. WCPFC is not explicitly requiring species-level ID given the difficulty at sea, but encouraging better notes (such as presence of spots on the belly, group size, proximity to shore, etc.) can hint at which type was involved. Over time, compiling these details could show, for instance, that most offshore interactions involve common bottlenose dolphins. Such nuance might matter for conservation, since coastal Indo-Pacific bottlenose populations could be more at risk if they were being affected.

- Linking with coastal research: Many Pacific Island nations have local studies on bottlenose dolphins (often related to tourism or conservation in reefs and lagoons). It would be useful to connect data from WCPFC (offshore fishery interactions) with these inshore studies. For example, if a particular island’s resident dolphins have been photo-identified and catalogued, and one of those individuals later shows up in an observer photograph from a fishing interaction, that would be critical information. It could show movement between coastal and offshore areas or highlight a new risk to a known group. Collaboration between fisheries observers and marine biologists (through data sharing agreements) can enhance understanding of dolphin ranging patterns and threats.

- Continued enforcement of dolphin protection policies: Although WCPFC has measures on paper, ensuring they are implemented is key. This means continued high observer coverage in purse seine fisheries (which has been generally good, ~80% or more coverage pre-COVID) to directly document any dolphin encirclements and confirm that release procedures were followed. For longline fleets, where human observers are few, ramping up electronic monitoring will help catch any non-compliance (e.g., if a crew were to mishandle or not report a dolphin caught on line). Transparency in reporting – including sharing incident narratives – will build confidence that bottlenose dolphins and other cetaceans are indeed being treated as the regulations intend.

Source documents: WCPFC Cetacean Bycatch Measure (2011-03) and national implementation reports; SPREP 2022 Pacific marine mammal status review (noting coastal bottlenose populations); IUCN assessments for T. truncatus and T. aduncus; case studies of dolphin release from tuna purse seines (e.g., ISSF best practice guidelines).

Spinner Dolphin (Stenella longirostris)

Latest assessment | Regional population monitoring (2018–2021); IUCN Red List 2018 (global) |

Status | Least Concern globally. Locally common around many Pacific islands, but susceptible to human disturbance. |

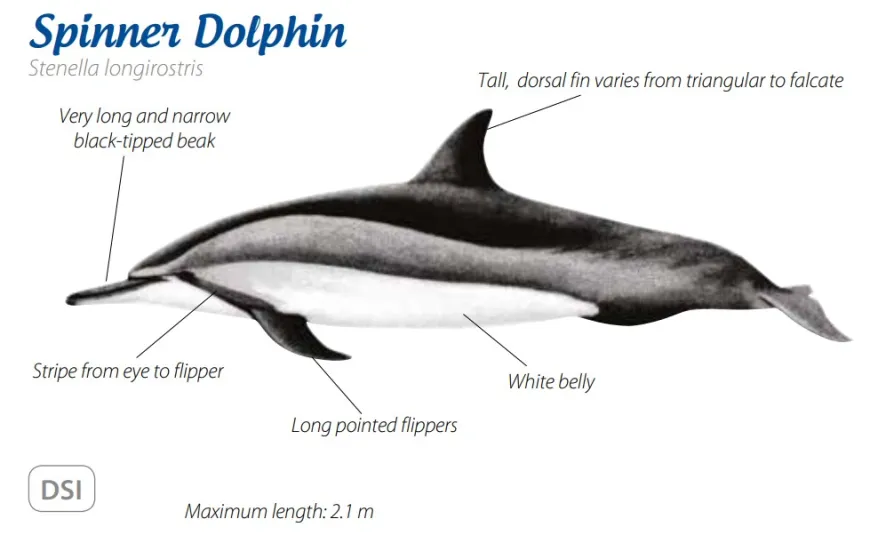

Key findings | Spinner dolphins are small (1.5–2 m) oceanic dolphins famous for their acrobatic spinning leaps. In the Pacific Islands region, they typically have a predictable daily pattern: resting in sheltered bays or nearshore waters by day and foraging offshore at night on fish and squid that come to the surface. Many islands have resident spinner dolphin communities that return to the same bays every morning – a behavior that has made them a focus of tourism in places like Polynesia and Micronesia. Overall, spinner dolphins are abundant across their range (hence global Least Concern status), and in the Eastern Tropical Pacific their numbers have rebounded significantly after being heavily depleted by historical tuna purse seining. In the WCPO, purse seine fisheries never targeted dolphins, so large-scale mortality events like those formerly seen in the Eastern Pacific have been avoided. However, spinner dolphins do still experience bycatch in the WCPO tuna fisheries occasionally. Observers have reported instances of spinner dolphins being encircled in purse seine sets – possibly when they were feeding in the vicinity of tunas or attracted to a FAD at night. Such events are relatively rare compared to the Eastern Pacific fishery of the past, but any single event can involve multiple dolphins due to their group living. Entanglement in netting (either purse seine nets or discarded nets) is another concern for this species, as is the case for many small cetaceans. Fortunately, most recorded WCPO interactions with spinner dolphins have resulted in the dolphins being released alive, reflecting both the dolphins’ agility and the crews’ efforts to follow dolphin-safe handling guidelines. Nonetheless, even non-lethal interactions (chasing or encirclement) can stress the animals, and thus mitigating all avoidable impacts remains a priority. |

Management | Spinner dolphins fall under WCPFC’s mandate to protect non-target species in tuna fisheries. The Commission’s measures (CMM 2011-03 and related provisions) explicitly ban intentional setting of nets around any cetaceans, which includes spinner dolphin schools. This ensures that the devastating “tuna-dolphin” fishing technique used in past decades in other oceans is not practiced in the WCPO. Moreover, if a spinner dolphin (or a group of them) is accidentally encircled during a set, the vessel must halt net hauling and release the animals as per the safe release guidelines. In practice, WCPO fleets have generally complied, and there’s an industry awareness that dolphin mortality would lead to bad publicity and possibly trade repercussions (many major canneries will not accept tuna caught with dolphin mortality, per dolphin-safe policies). Additionally, WCPFC requires detailed reporting of any dolphin interactions. Purse seine observers (who are on nearly all vessels) document these incidents, providing data on how many dolphins were involved and their fate. To further minimize risk, the Commission has promoted research into non-entangling FADs (reducing the chance spinners get caught in FAD structure) and has considered recommendations from the Scientific Committee to improve dolphin safety – for example, backing research into acoustic detection of dolphin presence around fishing grounds. At the national level, several WCPFC members (e.g., Fiji, French Polynesia, Palau) have designated marine mammal sanctuaries or protected areas, which, while aimed more at coastal activities, reinforce a general ethos of dolphin conservation that commercial fisheries are expected to uphold when operating in those zones. |

Fishery interaction profile

- Spinner dolphins are most active at night in open water, which overlaps in timing with many purse seine sets that target tuna at night (especially around drifting FADs). A typical scenario for an interaction might be: just before dawn, a purse seiner sets on a tuna aggregation that has been holding near a FAD overnight; unbeknownst to the crew, a pod of spinner dolphins was also feeding in that area under cover of darkness. As the net is pursed, some dolphins find themselves enclosed. Alternatively, spinners occasionally accompany yellowfin or skipjack schools (not as a regular association like in the Eastern Pacific, but opportunistically), so a daytime set could also capture them. Because spinner dolphins usually stick together, an entire subgroup could be in the net, not just one individual.

- When caught in a purse seine, spinner dolphins can often escape if given a chance – their small size and agility allow them to slip through openings or even jump over low sections of net. The main danger is entanglement in the mesh or corklines if they panic. Ensuring the net doesn’t have loose folds and keeping it open at the surface can prevent them from getting stuck underwater. On record, a number of spinner dolphin encirclements in WCPO fisheries ended with the dolphins released unharmed, which is encouraging. However, near-misses and minor entanglements likely happen more often than reported; a dolphin might briefly tangle and then free itself before anyone notices, for instance. Such events could still injure the animal (cuts or exhaustion).

- Spinner dolphins very rarely interact with longline gear due to their feeding habits (they tend to take small prey near the surface, not large bait from deep hooks). The bigger threat in longline operations is indirect – e.g., getting struck by a vessel or entangled in a loose line at the surface. That said, essentially all documented fishery interactions for spinners in the WCPO are with purse seines or drift nets (the latter now banned in high seas). Continued vigilance in purse seine operations, where the bulk of risk lies, is the cornerstone of mitigating impacts on this species.

Effective actions

- Dolphin observation and avoidance: Even though purse seiners in the WCPO aren’t targeting dolphins, they should still treat dolphin presence as a no-go indicator for sets. Captains and lookouts can use visual cues – e.g., flocks of seabirds behaving in certain ways can sometimes indicate dolphins (as dolphins will drive prey to surface for birds to pick). If any dolphin species are seen jumping or surfacing near a potential set area, it’s a strong sign to reassess. Some vessels also coordinate with each other; for instance, if one boat sees a large dolphin school in one grid area, they might radio others to be cautious when fishing nearby. This informal communication network can help avoid accidental encirclements.

- Net modifications and techniques: WCPFC has not made specific net modifications mandatory (unlike the Eastern Pacific which uses Medina panels for dolphin safety), but many modern purse seine nets by default have features that reduce dolphin entanglement – for example, smaller mesh in the upper net sections to prevent snout entrapment, and sometimes breakaway sections that can be opened quickly. Fleets are encouraged to maintain these dolphin-friendly designs. During sets, a technique similar to the backdown can be employed if dolphins are discovered: that is, reversing engines to create a slack “escape alley” at one end of the net. Training drills on emergency dolphin release could be introduced in observer programs or by proactive fishing companies so that crews react swiftly and correctly when needed.

- Post-encirclement monitoring: After any event where dolphins were in a net, even if all swam away, the vessel should spend additional time monitoring the area. Spinner dolphins, if stressed or injured, might linger or have difficulty keeping up with their group. Circling back to check can allow the crew (or observer) to verify that no animal was left tangled or injured. In some cases, observers have noted dolphins rejoining alongside the vessel later – possibly out of curiosity or in search of lost pod members. Such instances should be documented, as they might suggest that not all individuals recovered immediately. The crew’s responsibility doesn’t necessarily end the second the net is clear of dolphins; a brief, careful look can ensure no animal in distress is left behind.

Monitoring and cooperation

- High observer coverage continuity: The purse seine fishery in the WCPO had near 100% observer coverage pre-pandemic, which provided confidence that almost all dolphin interactions were recorded. It’s vital to return to and maintain that level of coverage (or equivalent electronic monitoring) because spinner dolphin interactions, while infrequent, tend to be stochastic – one vessel might have none for years and then one set accidentally catches a dozen. If that vessel happened to be unobserved, an entire pod could be killed without documentation. Thus, the Commission supports resuming full observer deployments and accelerating electronic monitoring programs as a backstop.

- Data sharing with IATTC (Eastern Pacific): The Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission has decades of experience managing dolphin bycatch in tuna fisheries, specifically with spinner (and spotted) dolphins. While the fishing method differs (since Eastern Pacific fleets used to intentionally set on dolphins), many of the safe release techniques and monitoring methods (such as specialized observer training, stress indicators for released dolphins, etc.) are highly relevant. WCPFC and IATTC scientists have been collaborating to some extent on bycatch issues; continuing this exchange will allow WCPFC to adopt or tailor the best practices from the Eastern Pacific. For example, the concept of a “quick dolphin mortality report” system or strict per-vessel dolphin mortality limits (as used in IATTC) could be adapted if ever needed.

- Community engagement and conservation synergy: Spinner dolphins are beloved in many Pacific communities — they are often part of ecotourism and local cultural narratives. WCPFC recognizes that saving dolphins is not just about regulations but also about public support. By engaging coastal communities and fishers (many of whom have seen dolphins daily since childhood) in reporting sightings of entangled animals or advocating for responsible fishing, compliance naturally improves. Some WCPFC members have funded community programs (via the Convention’s voluntary funds) to raise awareness on issues like not dumping plastics (which can ensnare dolphins) and promptly reporting any distressed dolphins around FADs or gear. This grassroots involvement complements the top-down management, creating a comprehensive approach to spinner dolphin conservation that spans from the fishing grounds to the shoreline.

Source documents: WCPFC Cetacean CMM 2011-03 (purse seine dolphin-safe provisions); Comparisons with IATTC dolphin conservation program outcomes; SPC Regional Observer Programme reports on dolphin interactions; national marine mammal sanctuary declarations in WCPO member EEZs.

How WCPFC manages cetacean bycatch

- Prohibition on intentional sets: WCPFC requires that purse seine vessels do not deliberately set nets around any cetaceans. Unlike historical practices in other oceans, WCPO tuna fishing must avoid using dolphins or whales to locate tuna. If any whale or dolphin is observed near a targeted tuna school, the set must be abandoned or delayed. This rule is fundamental and prevents many potential cetacean captures outright.

- Mandatory safe handling and release: If a cetacean is inadvertently encircled in a purse seine or caught on a longline, the crew is obligated to promptly and safely release the animal. In purse seine operations, this means stopping the net roll as soon as the crew realize a cetacean is in the net and not resuming fishing until the animal is free and clear of danger. They may use techniques like net slacking, backdown maneuvers, or opening a portion of the net. In longline operations, crews must cut the line or gently remove the hook to release the animal as quickly as possible, minimizing any additional injury. WCPFC has tasked its Scientific Committee to develop best-practice handling guidelines (drawing from FAO and other RFMOs) – for example, recommendations like not lifting dolphins by the tail, using stretchers for small cetaceans if needed, and methods to resuscitate animals that aren’t actively swimming. These guidelines are circulated to captains and included in observer training.

- No retention policy: All WCPFC members must enforce a ban on retaining any part of a cetacean caught in tuna fisheries. This means whales or dolphins caught incidentally cannot be kept for meat, teeth, or any other product – they must be released, dead or alive. This policy removes any incentive a vessel might have to target or not avoid cetaceans. It also ensures that any bycatch remains a conservation concern (a lost animal) rather than turning into a secondary catch. Even in cases where a small cetacean might die in the net, crews typically document it (for observer records) and then return the carcass to the sea, as landing it would be a violation.

- Crew training and guidelines: The Commission encourages members to provide education to their fishing crews about cetacean protection. Many fleets now incorporate a module on marine mammal interactions in their training – covering species identification, release procedures, and the legal importance of avoiding harm. Guidelines often emphasize the safety of both the crew and the animal, stressing that crew should never put themselves in peril to save an animal (for instance, diving into the net with a panicked whale is not expected). Instead, they are trained in using tools and vessel maneuvers to effect a rescue. Outreach materials, like waterproof posters or handbook cards on safe release, have been distributed on vessels as reminders.

- Reporting and transparency: WCPFC member countries are required to report all interactions with marine mammals in their Annual Reports (Part 1) to the Commission. These reports include data on how many cetaceans were encircled or hooked, which species (if known), and whether they were released alive or dead:contentReference[oaicite:8]{index=8}:contentReference[oaicite:9]{index=9}. Additionally, the Regional Observer Programme provides detailed incident logs from observer reports. The Secretariat compiles this information to monitor trends and compliance. Through this reporting, WCPFC can assess which fisheries or areas have higher interaction rates and may need additional attention. It also enables an evaluation of how well the no-setting and safe-release rules are being followed. For instance, if observers note any instances of non-compliance (such as not halting a net haul when a dolphin was present), those can be brought up in compliance reviews.

- Cross-regional cooperation: Cetacean conservation is a shared responsibility beyond WCPFC. The Commission collaborates with other tuna RFMOs and bodies like the International Whaling Commission (IWC) on bycatch mitigation. For example, there are exchanges of information with the IATTC regarding dolphin-safe fishing methods and with the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (which has dealt with whale shark and cetacean entanglements in nets). WCPFC’s Ecosystem and Bycatch Working Group serves as a platform to bring in expertise from outside organizations (like SPREP – the Pacific Regional Environment Programme) to keep measures up to date with global best practices. Furthermore, WCPFC members often participate in workshops under the Bycatch Mitigation Initiative of FAO or NGOs, and they bring back recommendations to the Commission. This cooperative approach ensures WCPFC’s cetacean measures remain effective and in line with international standards.

Key measure: CMM 2011-03 (Conservation and Management Measure for the Protection of Cetaceans from Fishing Operations, adopted 2011, under review for enhancement) underpins these rules, mandating non-entanglement, safe release, and reporting for all marine mammals in WCPO fisheries.

Data needs and next steps

- Enhance observer coverage and electronic monitoring: Improving monitoring is critical to understanding and reducing cetacean bycatch. The purse seine fleet already has high observer coverage (target 100%), which should be maintained, but longline fisheries (with only ~5% human observer coverage) require urgent improvement. Several WCPFC members are carrying out expanded trials of electronic monitoring (EM) on longliners – cameras and sensors can record cetacean interactions, providing data even when no human observer is aboard. Increasing the coverage (human or EM) will yield more accurate interaction rates and help identify high-risk areas or practices. Additionally, better data will enable scientific assessments like estimating mortality levels and comparing them to potential biological removal (PBR) thresholds for vulnerable populations.

- Mitigation research for longline depredation: A priority is to develop and test new methods to prevent whales and dolphins from depredating longline catches, thereby reducing bycatch. Ongoing studies include testing different hook types or hook guards that might prevent cetaceans from getting hooked when they take fish, using acoustic devices (pingers or even novel sounds that deter species like false killer whales), and exploring “economic mitigation” – e.g., sacrificing a portion of the catch to satiate the animals quickly so they depart. WCPFC’s Scientific Committee has recommended dedicated research efforts, possibly in collaboration with gear manufacturers and fleets, to trial such techniques in the WCPO context. If promising methods are found, the Commission could then consider making them part of the required mitigation toolkit for longliners in the future.

- Post-release mortality studies: It is not enough to assume that a released cetacean survives – some may die from injuries or stress after the fact. Tagging and tracking released individuals is therefore an important next step. The Commission is encouraging projects that attach satellite tags to whales or dolphins that were caught and freed (several members have research programs that could contribute, e.g., tagging false killer whales or pilot whales that interact with fisheries). By analyzing the movement and fate of these animals (for instance, whether they resume normal migration or if the tag shows the animal dying), scientists can gauge the true effectiveness of current release practices. If post-release mortality is high, it signals the need for improved handling or gear changes. These studies are logistically challenging but offer valuable feedback to refine bycatch mitigation strategies.

- Finer-scale data and species identification: Collecting more detailed data on each interaction will greatly aid mitigation. Observers should record not just the species and number, but also group size, presence of calves, the animal’s behavior, and exact interaction circumstances (time of day, gear phase, etc.). Such granular data can reveal patterns, like certain times or configurations leading to most problems. Furthermore, accurate species identification is essential – training observers to tell apart look-alike species (and to use cameras for verification) will help avoid lumping data into generic categories. As noted, distinguishing between similar dolphins (e.g., bottlenose vs. rough-toothed, or pilot vs. false killer whale at distance) can be tricky, so investment in identification guides, observer refresher courses, and perhaps AI-assisted photo ID tools (if camera footage is available) are on the table. With better species resolution, assessments can determine which exact populations are at risk.

- Adaptive management and area-based measures: The WCPFC may consider spatial or temporal management if data show cetacean interactions are concentrated in certain areas or seasons. For example, if a particular region of the high seas is identified as a hotspot for false killer whale bycatch in certain months, the Commission could discuss time-area closures or advisory zones to shift fishing effort away during those periods. Similarly, if spinner dolphin encirclements happen mostly near a specific island group’s FAD cluster, there could be cooperative arrangements with that coastal State to mitigate risk (such as moving FADs further offshore or seasonal suspensions of sets near shore). Adaptive management means the rules can become more nuanced and targeted as our knowledge improves. Any such measures would be developed in consultation with stakeholders to balance conservation with fishing needs, and would rely on the improved data collection outlined above.

- Capacity building for member states: Many WCPFC members are small island developing states with limited resources. To ensure cetacean bycatch mitigation is implemented effectively, the Commission continues to support capacity-building initiatives. This includes training workshops for national fisheries observers and enforcement officers on the cetacean measure requirements, funding for equipment (like line cutters, satellite tags for research, or even basic safety gear to aid releases), and assistance in developing national laws that mirror WCPFC’s protections. By empowering each member to enforce and contribute data on cetacean interactions, the overall effectiveness of the regional measures is strengthened. Several members have tapped into the WCPFC Special Requirements Fund to run projects like local language fisher education on marine mammal release, which can serve as models for others.