WCPFC Manta and Devil Ray Bycatch Mitigation Terms

This guide explains key practices and tools used by the WCPFC to reduce manta and devil ray (mobulid) bycatch and mortality. These terms appear in conservation measures and safe handling guidelines for mobulid rays.

📘 Definitions and Measures

No-Retention Policy: A rule prohibiting vessels from keeping any mobulid rays caught. Under WCPFC’s measure, all manta and devil rays must be released (whether alive or dead) and cannot be sold or kept. This removes any incentive to target these rays and ensures that bycaught individuals are returned to the ocean.

Safe Release Guidelines: Best-practice methods for handling and freeing rays with minimal harm. WCPFC’s guidelines (Annex 1 of the mobulid CMM) include using dip nets or slings to lift rays, cutting nets to disentangle them, and never hoisting rays by their tails or gill openings. Following these practices greatly improves the chances that released rays survive.

Key Shark Species: A designation by WCPFC that elevates certain species (including mobulid rays) for special monitoring and reporting. Once mobulids were listed as key species, observers began recording detailed data on each interaction. This status means annual catch reports must include mobulid bycatch and scientific efforts are focused on assessing their populations.

Post-Release Mortality: The percentage of animals that die after being released from fishing gear. Studies in the Pacific have found that mobulid rays can suffer high post-release mortality if handled poorly (over half may die in some cases). By using careful handling techniques (quick release, avoiding injury), fishermen can significantly reduce these delayed deaths.

Bycatch Reduction Devices (BRDs): Specialized tools or modifications to fishing gear aimed at reducing accidental catch of non-target species. For purse seine fisheries, experimental BRDs for mobulids include large mesh panels or escape openings that allow rays to exit the net. Some vessels also prepare canvas stretchers or “ray bags” to safely hoist and release rays. WCPFC encourages such innovation to further lower mobulid bycatch mortality.

Mobulid Rays in the WCPO

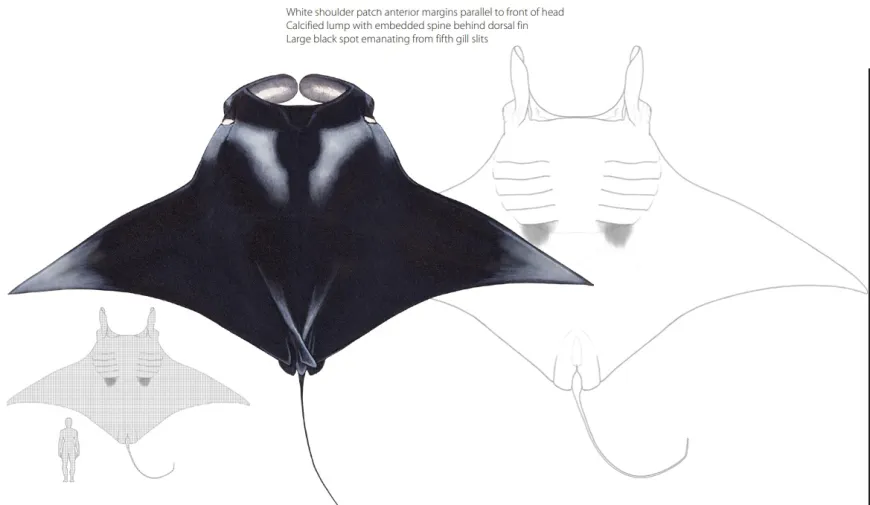

This page summarizes the status of manta and devil rays (mobulids) in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean (WCPO) and the bycatch mitigation actions adopted by the WCPFC. Four species of mobulid rays – the giant manta, spinetail devil ray, sicklefin devil ray, and bentfin devil ray – occur in the WCPFC area, all of which are classified as threatened (Endangered or Vulnerable) on the IUCN Red List. These rays are slow-growing, late-maturing, and give birth to only one pup at a time, making them extremely vulnerable to overfishing. Incidental capture in tuna fisheries (especially purse seine nets, and occasionally longlines) is a significant threat to mobulids, compounding historical targeted fishing for their gill plates. WCPFC’s conservation measures focus on eliminating directed catch of these rays, ensuring their safe release when bycaught, and improving our understanding of their interactions with fisheries.

WCPFC addresses mobulid bycatch through a strict no-retention policy, mandatory release protocols, and ongoing data collection. All vessels are prohibited from targeting or retaining mobulid rays under CMM 2019-05, meaning any manta or devil ray caught must be promptly released alive if possible. Crews are trained and encouraged to follow FAO-endorsed handling guidelines (now adopted in WCPFC’s measure) to maximize post-release survival – for example, using proper equipment like long-handled cutters, de-hookers, and lifting slings to avoid injuring rays. Purse seine vessels take special care when a ray is spotted in a net, pausing operations to disentangle and free the animal as per the safe release procedures. Every interaction with a mobulid ray is recorded in logbooks and by observers, and reported to WCPFC, allowing the Scientific Committee to monitor bycatch levels and the effectiveness of mitigation measures. Through these collective efforts – alongside national protections (some members have declared mantas fully protected in their EEZs) and global initiatives (e.g. CITES trade restrictions) – WCPFC aims to minimize fishery-related mortality of mobulid rays and support the recovery of their populations.

Giant Manta Ray

Latest assessment | No region-specific stock assessment; global IUCN status review updated in 2018 (original 2011 assessment). |

Status | Vulnerable globally (IUCN). Populations declining; listed as a threatened species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act (2018). |

Key findings | Giant manta rays are the largest mobulid, reaching up to 7 m wingspan, and are highly migratory across tropical and subtropical oceans. In the Pacific, they travel between coastal habitats (like cleaning stations on reefs) and offshore feeding grounds. Due to very low reproductive output (one pup every 2–5 years) and historical over-exploitation (targeted for their gill plates in parts of Asia), their numbers are believed to have declined significantly in recent decades. They are not commonly caught in WCPO tuna fisheries (encounter rates are low), but even infrequent bycatch can be impactful – every adult manta is important for such a slow-growing species. Genetic studies suggest Pacific giant mantas may comprise a single wide-ranging population, meaning losses in any part of their range (through bycatch or directed catch) can affect the overall population. |

Management | WCPFC’s mobulid ray measure (CMM 2019-05) affords full protection to giant mantas: vessels cannot retain them and must release any manta caught as quickly and safely as possible. Crews are instructed to keep mantas in the water during release if feasible – for example, by lowering the net or guiding the manta out an open escape route. If a manta is entangled or must be lifted, fishermen should use a large-mesh cargo net or strong canvas sling rather than a line or gaff. The measure’s Annex provides detailed handling do’s and don’ts to prevent injury (e.g. no lifting by the gills or cephalic lobes). Observers record all manta ray interactions, and WCPFC has encouraged members to report even anecdotal sightings, enhancing knowledge of where and when mantas occur. Internationally, giant mantas are listed on CMS Appendix I and CITES Appendix II – WCPFC’s actions complement these by ensuring that on the high seas, mantas are not harmed or traded. |

Notes | Because giant mantas are so iconic (and valuable alive for eco-tourism), several WCPFC members have domestic laws fully protecting them in coastal waters. Any interaction with a manta in the WCPO tuna fisheries is treated with high priority. Some fleets have voluntarily developed specific release tools (such as “manta ramps” or large strop nets) to improve how mantas are returned to the sea. As data collection improves, WCPFC will be able to identify if particular zones or seasons pose higher risk to mantas and consider additional management (e.g., advisory notices to avoid known aggregation areas during peak times). |

Range and fishery interactions

- Giant mantas have a broad range, roaming across the Pacific from near-equatorial waters out to subtropical regions. They often frequent productive zones (like upwellings or convergence fronts) where plankton and small forage fish are abundant. In the WCPO, mantas might be encountered by purse seine vessels particularly in areas where they come to the surface to feed. However, given their strong swimming ability and size, they can often evade nets; this makes actual captures infrequent relative to smaller rays.

- Longline interactions with mantas are rare but can occur if a manta becomes snagged or entangled in the fishing line or branchlines. Mantas do not typically bite baited hooks (since they feed on tiny plankton), but a feeding manta could accidentally swim into a line. Most documented fishery interactions with giant mantas in the WCPO have been in purse seine nets or occasionally in coastal gillnet fisheries (the latter being outside WCPFC’s high-seas jurisdiction but contributing to overall mortality).

- Even low levels of bycatch are a concern for mantas. A single death can have outsized effects on the population because each female produces so few offspring over her lifespan. This is why WCPFC management emphasizes preventing mortality entirely – the goal is that any manta that enters a net or is incidentally caught will be released alive and unharmed.

Effective bycatch mitigation for fleets

- Avoid encirclement if possible: Purse seine captains should be vigilant for the presence of mantas when setting a net. If a large dark shape (a manta) is seen in the area, some captains choose to delay or adjust the set to avoid capturing it. This proactive avoidance is the first and best step to mitigate manta bycatch.

- Prepare release equipment in advance: Vessels operating in manta-prone waters often carry a robust sling or stretcher specifically for handling big rays. By having this gear ready, crew can quickly deploy it when a manta is in the net – gently corral the manta into the sling underwater, then lift and release it over the side without ever pulling it onboard. Ensuring the manta stays in water (or is out of water for only a minimal few seconds) greatly increases survival chances.

- Never use sharp implements or excessive force: Crew must not gaff a manta or use hooks/ropes through its body to lift it. Instead, they should use handlines under the manta’s body or the aforementioned net sling. If the manta is tangled, carefully cut away the netting. The manta’s skin and gills are easily damaged, so all actions should be slow and deliberate, prioritizing the animal’s wellbeing over fishing operations.

Monitoring priorities

- Enhanced reporting of sightings and interactions: Given the relative rarity of encounters, WCPFC scientists have requested that even non-capture sightings of mantas by crews be reported when possible (e.g., if a vessel sees mantas aggregating, note the location). This can help map important habitats and times of year for giant mantas in the WCPO.

- Post-release survival tagging: To gauge how well mantas survive after release, researchers are exploring the use of satellite tags that can attach to a manta’s body temporarily after it’s freed. Data from these tags (e.g., dive behavior, travel paths) can indicate whether the manta resumes normal activity. A healthy post-release trajectory suggests current handling methods are effective, whereas a tag that reports a mortality would signal the need for improved practices.

- Coordination with tourism and coastal management: Many Pacific Island nations value mantas as a tourism resource (e.g., well-known manta viewing sites in Palau, Fiji, etc.). WCPFC can collaborate with such local efforts by sharing data on manta movements or threats. If a particular sub-population is identified (say, mantas that breed in one country’s waters but feed in another’s offshore areas), international cooperation will be needed to fully protect that group.

Source documents: WCPFC CMM 2019-05 (Mobulid Rays); WCPFC Scientific Committee papers on mobulid bycatch (2016 EB-WP and 2020 SA-IP reviews); CMS Appendix I listing for Giant Manta.

Spinetail Devil Ray

Latest assessment | No Pacific-wide stock assessment; IUCN Red List global assessment in 2019. |

Status | Endangered globally. Believed to be in decline due to bycatch and past targeted fishing pressure. |

Key findings | The spinetail devil ray (Mobula japanica) is a medium-large ray (disc width up to ~3 m) and is one of the more frequently encountered mobulid species in offshore fisheries. In the WCPO, observer data (since improved identification began in the mid-2000s) indicate that spinetail rays constitute a significant portion of reported mobulid bycatch, especially in purse seine sets around drifting FADs. These rays often travel in small groups near the surface to feed on zooplankton, which makes them susceptible to being encircled by tuna nets. While comprehensive population numbers are unknown, incidental catches combined with low reproductive rates have likely reduced their numbers in some regions. Historical records show that spinetail rays were sometimes landed in coastal fisheries (e.g., in Indonesia and the Philippines) for their gill plates, adding to fishing mortality. Overall, their conservation status (Endangered) reflects concern that without mitigation, even incidental kills can be unsustainable. |

Management | Under WCPFC’s 2019-05 measure, spinetail devil rays must be released immediately by all vessels. Although no species-specific rule exists (the measure covers all mobulids), this species benefits the most from strict adherence to the safe release guidelines because it is relatively commonly caught. Purse seine vessels are urged to follow the best practices: do not brail rays aboard with the tuna catch, but instead use a dedicated escape route or scoop net to remove and release them. Many fleets have incorporated these guidelines into their crew training. Additionally, WCPFC’s reporting requirements mean that every spinetail ray interaction (whether the ray is discarded dead or released alive) is logged. These data help in assessing whether additional measures are needed. For instance, if certain fishing grounds show higher spinetail bycatch, the Commission could consider advising avoidance of those areas during peak times. At present, compliance with the release requirement and gentle handling is the key management approach. Regionally, spinetail rays are also protected by virtue of CITES (restricting international trade of their parts), aligning with WCPFC’s no-retention rule. |

Distribution and interactions

- Spinetail devil rays are found throughout tropical and warm-temperate oceans. In the WCPO, they are encountered from the equatorial zone up to subtropics (e.g., as far north as the waters off Japan in warm seasons). They seem to favor open-water environments where they forage near the surface. Purse seine fisheries in the equatorial Pacific (10°N–10°S band) report most of the spinetail ray bycatch, often during sets on tuna schools associated with FADs. The structure and cover provided by FADs may attract small baitfish and plankton, indirectly drawing in rays.

- Interaction rates in purse seine gear are generally low (on the order of a few rays per hundred sets), but because the tuna fishery effort is very large, those small numbers accumulate. Prior to the 2010s, many of these rays might have been misidentified or not recorded; improved observer training has increased reporting of Mobula japanica specifically. Longline fisheries occasionally snag spinetail rays, typically when a ray becomes entangled rather than hooked. Such events have been recorded, but are uncommon compared to purse seine captures.

- When captured in a purse seine, spinetail rays face risks of injury from net pressure or being hit by other fish. If they are hauled onboard in the brailer along with fish, the ray can be badly hurt or suffocate. That’s why current guidelines stress removing rays separately from the main catch. Data from other oceans (e.g., Eastern Pacific) suggest that following best practices can drastically improve survival – fleets that adopted gentle handling have much higher live-release rates for mobulids.

Effective actions for fleets

- Have a release plan for every set: Crew should be assigned roles in case a ray is in the net. For example, one team readies the “ray release” net or canvas sling while others carefully gather the ray. By planning ahead (as part of the pre-set toolbox talk), the vessel can respond faster and more calmly when a ray is encountered.

- Minimize air exposure and handling time: If a spinetail ray is entangled, stop the net haul as soon as it is safe to do so. Gently disentangle the ray underwater if possible. If the ray must be brought on deck, immediately cover it with a wet cloth (to keep it moist and calm) and carry it to the railing for release. Ideally, two or three crew members can do this swiftly for a medium-sized ray. The entire process from capture to release should be under a few minutes.

- Document the condition on release: Whether an observer is onboard or not, crew should note if the ray swam away strongly or was released in a weakened state. This information (often recorded by observers) is important to evaluate the effectiveness of handling. Over time, patterns like “rays caught by certain vessel practices have higher mortality” can be identified and addressed through improved techniques or gear changes.

Data and monitoring needs

- Species identification and training: Continual emphasis in observer programs on distinguishing Mobula japanica from other rays is needed. Misidentification can lead to underestimating how many spinetail rays are affected. Providing observers with clear ID photos (e.g. spinetail rays often have a distinctive spine at the end of the tail and specific dorsal spot patterns) and possibly genetic ID tools for ambiguous cases will improve data quality.

- Post-release survival studies: Building on initial studies, WCPFC supports efforts to tag released spinetail devil rays with pop-up satellite tags to monitor their fate. A key question is what fraction of “released alive” rays survive long-term. Early research indicates that some do not survive beyond 1–2 days due to internal injuries. Identifying the causes (such as pressure trauma or rough handling) can guide better practices or technological fixes (like gentler net retrieval methods).

- Hotspot analysis: As more data accumulate, scientists plan to analyze whether there are spatial or temporal hotspots for spinetail ray bycatch (for example, a particular area of the WCPO where ray encounters peak, or certain months when rays congregate). If such patterns emerge, management could consider advisories or even time-area closures to avoid high-risk interactions during those periods.

Source documents: WCPFC CMM 2019-05 Annex 1 (Safe Release Guidelines); SPC-OFP analyses of mobulid bycatch (2016, 2020); Pacific post-release mortality studies for Mobula japanica.

Sicklefin Devil Ray

Latest assessment | No dedicated assessment in WCPO; IUCN Red List global assessment in 2019. |

Status | Endangered globally. Data deficient in the Pacific, but considered at high risk if catches are not controlled. |

Key findings | The sicklefin devil ray (Mobula tarapacana) is a large, oceanic ray that can exceed 3 m in disc width. It is believed to be more pelagic and deeper-diving than other mobula species. Sicklefin rays are encountered only occasionally by WCPO tuna fisheries – they appear to be relatively rare in observer records. When they do appear, it’s often a solitary individual caught in a purse seine net. Their tendency to dive to depth (sometimes hundreds of meters) may keep them away from surface fishing gear much of the time. However, they do surface to feed, and at those times can be vulnerable. Little is known about their population size or structure in the Pacific; no specific surveys exist. Given their low reproductive rate (likely one pup every 2–3 years) and observations of declining trends in other oceans, they are assumed to be in need of strict protection. The Endangered listing by IUCN underscores concern that even incidental catches could be detrimental. |

Management | WCPFC’s broad mobulid measures apply fully to sicklefin devil rays. While encounters are rare, vessels are still required to release them unharmed and cannot retain any part of them. Because of the ray’s size and strength, special care is needed during release – the guidelines in Annex 1 specifically note using cargo nets or slings for any ray too large to handle by hand (which includes most adult sicklefin rays). The Commission has not implemented any ray-specific spatial closures or gear modifications (due to limited data on this species), but it remains vigilant. Each reported capture is scrutinized. For instance, if a particular vessel or area sees a sicklefin ray caught, WCPFC may inquire whether conditions or practices could be adjusted to prevent a repeat. At the international level, protections like the ban on international trade (CITES) and CMS listings provide additional safety net for this species. The WCPFC measure ensures that even on the high seas, where national laws don’t directly apply, sicklefin rays receive consistent protection via release requirements. |

Habitat and fishery interactions

- Sicklefin devil rays are true denizens of the open ocean. They have been recorded around remote islands and seamounts (for example, tagging studies elsewhere have shown them associating with underwater features), but they also undertake long migratory journeys. In the WCPO, their distribution likely overlaps with tuna fishing grounds broadly, but their low encounter rate suggests they are not very abundant or frequently at the surface. When they do come near the surface to feed, they could be inadvertently encircled in a purse seine set targeting tuna or associated species.

- Purse seine interactions are the primary concern, as few (if any) sicklefin devil rays have been reported caught on longlines in this region. Their diet of deepwater fish and plankton means they seldom go after baited hooks. Nevertheless, if a ray does get hooked or entangled on a longline, it often results from the ray’s body snagging a line rather than taking the bait. Such cases are extremely infrequent. Most WCPO records of this species come from purse seine observer reports, and even those are sporadic.

- Given the low number of observations, each interaction is valuable data. WCPFC scientists treat any reported sicklefin ray capture as an important event to study. For example, details like the ray’s size, condition (released alive or dead), and the set circumstances (FAD vs free school, time of day) are analyzed to glean insights. So far, no clear pattern has emerged (no “hotspot” for sicklefin bycatch is known), which suggests that avoiding these rare events is challenging beyond the general mitigation already in place.

Recommended handling

- Use heavy-duty release gear: Because an adult sicklefin ray can weigh several hundred kilograms, a purse seine crew should never attempt to lift it by hand. The recommended approach is to maneuver the ray into a large mesh cargo net or a robust canvas sling while it’s still in the water. Using the vessel’s crane or power block (with the net attached) to slowly raise the ray out of the net and lower it over the side is the safest for both the ray and the crew.

- Keep the ray horizontal and supported: A sicklefin ray’s body needs full support when lifted. Crew should ensure the ray’s pectoral fins (wings) are spread naturally and not bent sharply. If using a sling, center the ray’s body on it so that the head and tail aren’t drooping. The ray should be released by submerging the sling at the surface, letting it swim out on its own if possible.

- Be prepared to cut the net: In some cases, if a ray is extremely large or thrashing in a way that complicates handling, the captain may decide to sacrifice a portion of the net to free the animal (by lowering a section of corkline or cutting the net webbing around the ray). While losing some netting is costly, WCPFC members recognize that saving a critically endangered ray is more important, and the measure expects crews to prioritize the ray’s safe release over gear retention.

Data gaps and research

- Population connectivity: It’s unknown whether the sicklefin devil rays observed in the WCPO are part of a larger Pacific-wide population that also traverses the Eastern Pacific or Indian Ocean. Collecting tissue samples from any individuals encountered (for genetic analysis) could help determine if there are distinct sub-populations. Such information is crucial for assessing the species’ status; a small isolated population would be at greater risk than a large interconnected one.

- Deep habitat use: Researchers are interested in how often and why this species comes shallow (into fishing gear range). Using satellite tags that record depth could reveal the daily habits of sicklefin rays – for instance, do they spend daylight hours at 500 m and only surface at night? If so, certain fishing practices (like setting at particular times) might pose less risk. Understanding their ecology better could lead to refined mitigation (e.g., avoid setting nets at dusk if that’s when rays are near-surface).

- Inter-regional cooperation: The rarity of WCPO sightings means that data from other regions (like Indian or Eastern Pacific Oceans) is valuable to fill the knowledge gap. WCPFC’s Scientific Committee works with other tuna RFMOs to share mobulid bycatch information. If a pattern or effective mitigation is discovered elsewhere for sicklefin rays, the WCPO can adopt similar strategies proactively.

Source documents: WCPFC CMM 2019-05; WCPFC observer data (rare mobulid encounter reports); IUCN Red List (2019) assessment for Mobula tarapacana.

Bentfin Devil Ray

Latest assessment | No formal assessment specific to WCPO; IUCN Red List global assessment in 2019. |

Status | Endangered globally. Not well quantified in the Pacific, but likely under pressure from bycatch and other threats. |

Key findings | Bentfin devil rays (Mobula thurstoni) are among the smaller mobulid species, with a maximum disc width of around 1.5–1.8 m. They are distributed in tropical and subtropical waters worldwide. In the WCPO, bentfin rays have been recorded by observers in tuna fisheries, though distinguishing them from other mobulas is sometimes challenging. This species often occurs in small schools and is known to utilize both pelagic and coastal habitats (more so than the strictly oceanic sicklefin). They may be somewhat more likely to be found around islands or semi-enclosed seas (like archipelagic waters of Indonesia or the Philippines), but they also venture into the open ocean. Bycatch records in the WCPO indicate low encounter rates, similar to sicklefin rays. However, because bentfins are smaller, they might have been under-reported historically (easier to miss in a big net haul). Their Endangered status globally is based on evidence of declines due to fishing (including gillnet fisheries in some areas) and extremely low reproductive turnover. As with other mobulids, any mortality is a concern since population growth is very slow. |

Management | WCPFC’s measure doesn’t differentiate bentfin rays from other mobulids – all must be released and none can be kept. In practice, handling a bentfin ray is relatively easier than a giant manta or sicklefin ray, due to the smaller size. The safe release guidelines advise that smaller rays (under ~30 kg) can be lifted by two people supporting the wings. This is applicable to many bentfin ray individuals. Still, careful technique is important: even a smaller ray can be injured if grabbed incorrectly. The Commission’s emphasis has been on training crew to identify these rays (so they recognize it’s a protected mobulid and not, say, a harmless skate) and to follow the release protocols. Reporting of bentfin ray interactions is mandatory, and those records are compiled to see if any patterns emerge. So far, no specific hotspots for bentfin bycatch have been flagged in the WCPO, and their infrequent capture means broad measures (like the existing release requirement) are deemed sufficient at present. Nonetheless, the WCPFC Scientific Committee keeps bentfin rays on the radar, ready to recommend further action if needed. |

Fishery profile

- Bentfin rays occupy both offshore waters and areas not far from land (especially around productive reefs or shelves where plankton gather). In the Pacific, this means a bentfin ray might be encountered by a range of fisheries, from purse seiners in the high seas to artisanal nets in coastal zones. Within WCPFC’s purview (mainly the purse seine and longline fisheries), bentfin bycatch is relatively uncommon. When it does occur, it’s most likely in purse seine sets in tropical waters. For example, observers have noted occasional captures in the western equatorial Pacific purse seine fishery, perhaps when these rays are aggregating to feed.

- Because bentfin rays are smaller, they could sometimes escape nets by finding gaps or being pushed out with the water flow during net hauling. Those that do get caught in purse seines typically come up with the brail. If unnoticed, they could end up on deck mixed with tuna. This underscores the importance of diligent observation by crew and observers during brailing – spotting a ray in the catch at an early stage allows for quick intervention.

- Longline interactions with bentfin devil rays are extremely rare. As filter feeders, bentfins are unlikely to bite a baited hook. There’s a slim chance one might entangle with a line near the surface, but few if any such cases have been documented. Therefore, mitigation in longline fisheries is more about general best practices (e.g., cutting loose any ray seen tangled on the line) rather than species-specific rules.

Handling best practices

- Swift, gentle release: For a bentfin ray brought aboard in a brail, the crew should act immediately. Using a wet tarp or cloth to cover the ray can calm it if it’s thrashing. Then, two crew members (one holding each wing near the base) can lift the ray and slide it back into the sea, making sure it goes in head-first. This entire process should be done as smoothly as possible to avoid dropping the ray or causing it to hit the side of the vessel.

- Check for entanglement: Often, a ray might come aboard with some netting still wrapped on it. Crew must carefully cut away any mesh or line from the ray’s body before release. Common spots to check are around the wings and tail. Removing all entangling material ensures the ray isn’t hindered or wounded after it swims away.

- Crew safety and ray safety: While bentfin rays are not aggressive, they do have a tail spine that can inflict a wound (similar to a stingray’s barb) if mishandled. Crew should avoid the tail region during handling or use gloves and tools to control it if necessary. By handling the ray by its sides and keeping clear of the tail, they protect themselves and also avoid injuring the ray’s sensitive tail.

Monitoring and research

- Increasing data resolution: One challenge is ensuring that bentfin rays aren’t simply recorded as “unidentified mobula.” The more observers can confidently distinguish M. thurstoni, the better researchers can assess its bycatch frequency. Development of better identification keys (e.g., noting the distinct coloration or fin shapes of bentfins) is underway to assist observers in the field.

- Community and fisher science: In areas where scientific observer coverage is low, WCPFC is considering ways to leverage fishers’ knowledge. For instance, encouraging fishers to report sightings of ray schools or unusual bycatch through logbooks or apps can supplement formal data. Over time, this might highlight previously unknown areas where bentfin rays congregate, allowing for proactive management.

- Life history studies: More research is needed on bentfin devil ray reproductive biology and lifespan, much of which comes from studies outside the WCPO. WCPFC can support collaborations with academic scientists to study any specimens (e.g., if a dead specimen is collected, it could be examined for age, maturity, etc.). Understanding these parameters better will improve risk assessments for bentfin rays and ensure that WCPFC measures continue to align with the species’ conservation needs.

Source documents: WCPFC CMM 2019-05 (mobulid protection); SPC/Scientific Committee bycatch data review (2020); IUCN Red List assessment (2019) for Mobula thurstoni.

How WCPFC manages mobulid ray bycatch

- Prohibition on retention and targeting: All WCPFC members must enforce a ban on deliberately fishing for manta or devil rays. Any mobulid ray caught incidentally cannot be retained, transshipped, or landed (except for limited cases like surrendering a dead specimen to authorities for research or food, as allowed under the measure). This zero-retention rule (CMM 2019-05) aligns with similar bans in other oceans and removes economic incentives (such as the gill plate trade) from the WCPO tuna fisheries.

- Mandatory safe handling and release: WCPFC requires that vessels release mobulid rays as soon as possible, with minimal harm. The Commission adopted detailed guidelines (initially non-binding, now referenced in the CMM’s Annex) instructing fishers on proper techniques. These include instructions for purse seiners to avoid lifting rays out of water when possible, to use nets or stretchers for any heavy ray, and for longliners to cut the line close to the hook rather than try to haul a ray on board. Members are expected to provide the necessary equipment (e.g., line cutters, dehookers, lifting slings) on vessels and ensure crew are trained in their use.

- Observer coverage and reporting: Through its Regional Observer Programme, WCPFC monitors compliance and gathers data on ray interactions. Observers (where present) record each mobulid bycatch event, noting the species, size, condition (alive or dead, injured, etc.), and the handling methods used. Additionally, countries report mobulid bycatch numbers in their annual national reports. This transparency allows WCPFC to track how well the measures are working and which fleets or areas might need additional attention. Efforts are ongoing to increase observer coverage in longline fisheries and to implement electronic monitoring, so that even rare events like a ray capture are documented.

- Encouraging best practices and innovation: WCPFC doesn’t just mandate releases; it also encourages the fishing industry to develop and share best practices. For example, some fleets have designed special equipment (like “hopper cover nets” that prevent rays from falling into fish holds, or built-in escape panels in purse seine nets) – the Commission facilitates workshops and information exchange so that these ideas can spread to all members. The mobulid CMM explicitly calls for the Scientific Committee to recommend improvements to handling practices as new research becomes available, ensuring that the guidance evolves.

- Cooperation with other RFMOs and conventions: The WCPFC mobulid measure was developed in harmony with similar measures in the IATTC and IOTC, ensuring a Pacific-wide approach to ray conservation. Moreover, by implementing the no-retention and safe release rules, WCPFC members support broader international commitments (like CITES trade controls and CMS protections for these species). This collaborative stance means a vessel fishing in the WCPO operates under nearly the same rules regarding mobulid rays as it would in adjacent oceans, creating a consistent blanket of protection for the animals.

- Continuous review and adaptation: Mobulid rays have been incorporated into WCPFC’s Shark Research Plan and Bycatch Work Programme. The Commission has tasked scientists with exploring options for a quantitative assessment or risk assessment of mobulid populations by gathering more data (targeted for initial results by 2023). As more is learned, WCPFC can adjust its measures – for instance, if a particular gear modification dramatically lowers ray bycatch, it could be mandated in the future. The current strategy is adaptive management: implement precautionary rules now (given the known vulnerability of rays), study the outcomes, and refine measures as needed to better protect these species.

Key measure: CMM 2019-05 (Conservation and Management Measure on Mobulid Rays) provides the regulatory framework for these actions, building on earlier non-binding guidelines (2017) and aligning WCPFC with global conservation efforts for manta and devil rays.

Data needs and next steps

- Higher monitoring coverage: Increase observer presence and electronic monitoring on vessels to capture mobulid bycatch events, which are relatively rare and easily missed with low coverage. A target is to move beyond the minimum 5% observer coverage in longline fisheries and explore 100% video monitoring in purse seine fleets, ensuring that every ray interaction is observed and evaluated.

- Better species-specific data collection: Continue training for observers and crew on identifying mobulid rays to species level (giant manta vs. various devil rays). Historically, many records were simply “Manta/Devil ray (unidentified)”. By improving identification, WCPFC can detect if certain species (e.g., spinetail vs. bentfin) are more impacted and tailor measures accordingly. Collection of biological data (size, sex, tissue samples for genetics) during interactions should be enhanced under strict protocols so that it doesn’t harm the animal.

- Post-release mortality research: Support studies using satellite tagging and tracking of released rays to determine their survival rates and behavior after release. This research is critical to quantify the true benefit of the safe release guidelines. If a significant proportion of rays are still dying after release, further changes (or additional care, like longer revival times in water) might be necessary. Several such studies are currently underway in the Pacific, and their results in the next few years will inform WCPFC if adjustments to the protocols are needed.

- Innovative mitigation trials: Encourage and evaluate new techniques or gear modifications that could reduce ray bycatch or improve survivability. This could include testing escapement devices in purse seine nets (for example, large openings at the top of nets that allow rays and other megafauna to escape while fish are retained), or acoustic deterrents that might keep rays away from fishing gear. WCPFC can facilitate pilot projects and, if successful, promote the adoption of effective methods across all fleets.

- Risk assessment and potential quotas: As data improves, perform an ecological risk assessment for mobulid rays in the WCPO tuna fisheries. This analysis would estimate the level of fishing-induced mortality each species can sustain. If it turns out that even with releases there is a notable impact, WCPFC might consider setting explicit limits or reference points for mobulid bycatch (for instance, a maximum allowable mortality, after which additional mitigation steps kick in). Such an approach would integrate mobulids into the overall fisheries management framework more formally.

- Strengthen national and regional synergy: Work closely with member countries to ensure that measures at the WCPFC level are reinforced by domestic regulations. For example, if a nation has a shark/ray sanctuary in its waters, sharing information about ray movements can help WCPFC understand how high-seas bycatch might affect that sanctuary’s population. Similarly, capacity-building initiatives (funded through WCPFC or partners) should continue to help small island developing states implement observer programs and crew training, so the mobulid measures are effectively carried out in all fleets, large or small.